R

Readers of David Diop’s previous book, which received the International Booker Prize and is now considered a classic in war literature, are unlikely to forget the impact it had. At Night All Blood Is Black follows the story of a young Senegalese soldier who is drafted to fight for France in World War I and is subjected to brutal conditions in the trenches. The novel masterfully blends raw horror, poetic language, and nuanced reflections within its concise pages. In his latest work, Diop uses his expansive knowledge to explore an earlier period of interaction between Europe and Africa. Beyond the Door of No Return tells the tale of a French botanist from the Enlightenment era who travels to Senegal to study plants, but finds himself consumed by love for an African woman.

Michel Adanson, in his old age, documents a story of love and desire in a journal bound in leather. He hopes his daughter will one day discover and read it. After keeping his emotions locked away for 50 years, he reminisces about the fateful night in 1752 when he first heard about a woman who had been kidnapped and sold into slavery, but miraculously found her way back. With the guise of studying plants, Adanson embarks on a journey to Cap-Vert, determined to find this woman like a knight on a quest.

Diop’s imaginative additions to the biography of Michel Adanson (1727-1806) include his fixation on Maram Seck and his deathbed revelation of a hidden sorrow he experienced in Africa. Adanson, a French naturalist who wrote Histoire naturelle du Sénégal upon returning to Paris, dedicated much of his later years to research that was never published. Diop’s fictional exploration focuses on the intriguing and fertile topic of Adanson’s experiences in Africa and what he may have been unable to share with the Académie des sciences. What emotions and thoughts may have consumed the brilliant young man during his time there in the 1750s? How would he have conveyed them?

He describes the stories with a romantic and dramatic flair, showing a deep appreciation for Senegalese oral traditions. Adanson wrote in French, but this edition has been translated into English by Sam Taylor. He stresses that the majority of the conversations he recounts were in Wolof, shaped by its unique rhythms and nuances. He is critical of his European peers who continue to view Africans as inferior without attempting to learn their languages. In his opinion, the “beautifully delicate” Wolof language holds the key to understanding its people, containing all the richness of their humanity.

Adanson paints vivid images of communication and attentive listening. As a village leader speaks into the night, with eyes gazing at the stars, Adanson is reminded of their own smallness in a vast and enigmatic world. The focal point of the story is Maram’s personal account, as Adanson recalls her recounting it in a dimly lit village hut, illuminated by the faint blue glow of the ocean.

If this comes across as overly sentimental exoticism, be cautious of Diop’s methods of subverting it. The Wolof mourner, who speaks with heartfelt emotion while gazing at the stars, may actually be an incestuous uncle who has exploited his own niece. The tub filled with fish and glowing saltwater is not meant for the purpose of providing a mesmerizing experience for Adanson with its “sea light”, but rather as a source of food for the resident snake.

The novel contains numerous frame narratives, evoking the spirit of Joseph Conrad. The main story, narrated by Adanson, is surrounded by other characters and considerations. Diop takes a risk by dedicating the first section to Adanson’s daughter, Aglaé, and her complicated life and feelings towards her father’s obsession with botany. While this biographical aspect is intriguing, it is unclear where the main plot will unfold. However, as the book progresses, we return to the beginning and find pleasure in meeting Aglaé in her greenhouse. It becomes evident that this is a story about unexpected inheritances and how they can shape lives in unexpected ways. The inheritors have their own lives to live, providing a balance to the emotional intensity of Adanson’s tale.

Human actions do not completely remove the plants from the land, as seen in Adanson’s contemplation of the destruction of ebony forests for furniture and his own act of burning down a forest. Maram, a healer, views herself as deeply intertwined with the plants and animals of the wilderness. She even wears the skin of a giant boa, a mystical entity that possesses and guards her. Adanson is both physically and mentally drawn to her and is amazed by her strong connections with other species.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

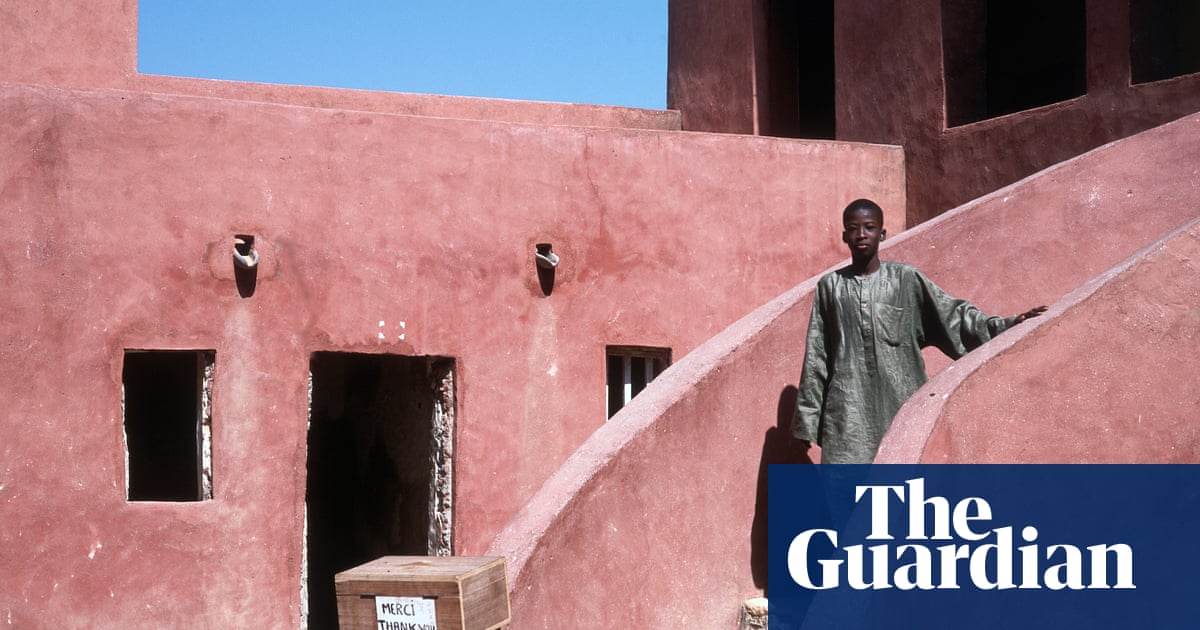

However, the overwhelming impact of the transatlantic slave trade surrounds them. Adanson stands in the eerie desert and contemplates the countless individuals who disappeared into the vastness of the ocean. Diop’s chosen title references Gorée Island, the largest of the fortress towns where enslaved Africans were transported from. This island was known as “the gateway of no return”. Today, Gorée is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, preserved in memory of its dark history and the suffering endured by those who were taken from there. Diop’s book serves as another type of tribute, shifting from tales of fantastical revenge to the sorrowful reflections of a traveler who remained silent for too long.

Source: theguardian.com