T

This is a tale of a man, men, and the concept of representing something greater than oneself. It explores the fleetingness of life and the importance of preserving fragments of history and legend before they disappear completely. It centers around a captivating notion and the surrounding islands that once embodied it. Ultimately, it delves into the idea of acceptance and making peace with the fact that something that once held great significance may never hold the same weight again.

The gentleman, now 86 years old, sits in a wheelchair but maintains a sturdy posture. He leans on a cane in his dominant hand, allowing his elbow to rest on the back of his seat. Tucked between the open collars of his vibrant orange shirt and the lapels of his suit is a delicate chain with a crucifix pendant. This was gifted to him by his mother to calm his nerves before an important school match. He has worn it every day since, except for one instance in Adelaide where it became unhooked and was discovered by a journalist. Reflecting on the trend of young men wearing multiple chains, he remarked, “You see young men now with six chains around their neck. They have achieved wealth and success, which is why they have six chains. I wear this to remind me not of my past, but of my future. My mother always told me to keep God at the center of all my endeavors.”

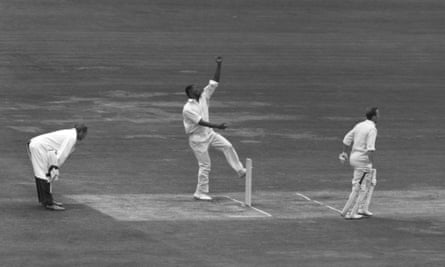

Until now, I only knew of ‘Wes Hall’ as a legend, an abstract concept, a bedtime tale passed down from my father – who witnessed him at The Oval in 1966 (“with his shirt billowing and jewelry flying”) and could never forget the sight. The exceptional fast bowler. The refined fighter. The endless run-up, the never-ending spells. Brisbane in 1960. Lord’s in 1963. The original. And suddenly, he is here, sitting with a small group of loved ones in the back room of the Union Jack Club near Waterloo station, the master storyteller playfully sharing more tales. “You see, they always said I was talkative…”

S

Some individuals have such expansive lives that they feel they are not only themselves, but also the essence of every person they encounter. Despite the twists of luck and destiny that transformed his childhood aspirations into a prominent role during the golden era of the West Indies, followed by a period of exploration in the bustling cities of Northern England, and later years as a successful entrepreneur, government official, and occasional manager of the West Indies team – and now, in his current form as a wandering musician with a completed body of work in hand – Hall remains convinced that a greater power has been directing his path.

He was not the initial one. The Caribbean had previous experience with swift bowlers. The renowned all-rounder, Learie Constantine, was believed to be just as fast on his best days. George Francis and Herman Griffith delivered quick balls during the wars. Manny Martindale was exceptional. The incredibly intimidating Roy Gilchrist and Charlie Griffith, who is still a close friend to Hall, were fierce competitors. However, none could compare to Wes Hall.

Tony Cozier described his athleticism as legendary, noting that he had the physique and strength of a bodybuilder. Even Ted Dexter, the only Englishman to truly challenge him, was amazed at his speed, which was faster than any bowler he had ever seen. In 1966, Muhammad Ali visited Lord’s while on tour in Europe and Canada. Despite being unimpressed by the batting, Ali was in awe of Hall’s performance, with his eyes ablaze and the winds of change driving him through the crease. Hall fondly remembers Ali telling him that if he had his stamina, he could fight three men in one night with ease. Ali even wrote in his book about Hall’s impressive fitness, which was particularly noteworthy considering it was 1966. Hall wonders what Ali would have said if he had seen him bowl in the 1963 Test match.

H

Everyone is a resident of all places. The renowned Caribbean historian, CLR James, described him as a person who radiates kindness from every part of his being. He is a part of Barbados, the highly fertile land of his birth, which has produced a remarkable number of exceptional cricketers per capita compared to any other place on the planet. He also belongs to the entire region: Jamaica, where he was embraced as one of their own after his impressive performance of taking seven English wickets on a challenging pitch at Sabina in 1960, marking his debut in a major series; and Trinidad, where he spent many years working and playing.

Australia loved him too, for his central role in the landmark rubber of 1960-61, crowned by his final over at the Gabba to clinch the Test game’s first ever tie. And then of course there’s the old country, land of “Cromwell, and all those guys and ladies”.

It was 1957 when the teenager first touched down in England. Raw, ungrooved, struggling with his run-up, he had a quiet tour with the ball but a revelatory one of the mind. Traipsing round the provinces, it struck him that he knew more of the history of this place than he did of his own. Unable until then to find “the good graces to study West Indian history”, Hall took to the books, determined that whatever he found out should infuse his understanding of the quest to which his life was about to be hitched.

His relationship with England became stronger over time. In the 1960s, he spent his summers there, starting as the club pro at Accrington in the Lancashire league and later at Great Chell in Staffordshire. Despite being a young black man at Accrington, Hall felt welcomed and accepted by the local community. In his new autobiography, Answering The Call, he shares, “I had many white people who I grew up with and loved. When I went to Accrington, I was treated with respect and lived a good life.” He was actively involved in all aspects of the club, including developing a bond with a talented 13-year-old left-arm spinner named David Lloyd. He even accompanied Lloyd to his first Test match at Trent Bridge.

In 2018, Bumble reflected on the impact of having Hall around. Witnessing a top athlete competing with local players against a rival team, easily fitting into the community, and striving to excel for both himself and his team taught me the true essence of cricket.

During this period, there was a sense of urgency. Lessons were taught quickly. The importance of codes and ethics was emphasized. Hall’s enthusiasm and inquisitiveness were channeled into a cricket team with a greater purpose beyond simply playing the game. They aimed to make a positive impact on the world around them.

“In the Caribbean, the principles of cricket have not only influenced the players themselves, but also the way of life,” stated English journalist EW Swanton in the late 1950s. However, although Swanton observed a fervent dedication to the sport, it also had a political undertone. Like any significant revolution, it required a leader to inspire and energize it.

F

Worrell’s excellence as a cricket player was just one of his many admirable qualities. He was part of the talented trio of Worrell, Weekes, and Walcott from Barbados who brought glory to the West Indies after World War II. Worrell was known for his sophistication, intelligence, and determination to uplift his community.

Worrell made history as the first black captain of the West Indies during the 1960/61 tour of Australia. He had a clear plan in place for his top fast bowler, Hall, whom he saw as an ambassador and spy tasked with gaining knowledge about the structures and systems in countries with more developed cricket programs. Worrell strategically guided Hall through the English leagues and Australian state cricket, even securing employment for him in Trinidad for three years. Hall was not the only beneficiary of Worrell’s efforts. In fact, he even referred to Worrell as deserving of a Nobel prize for his vision and dedication in shaping the lives of young men.

He explains that Sir Frank was like a father to him and even served as the best man at his wedding. During the highly talked about Australia tour, Sir Frank only held three team meetings over the course of five to six months. However, what set him apart was that any player could approach him or the captain with any issues, which is not always the case. The renowned CLR James wrote a letter to Sir Frank, expressing that if the team could perform well, it would signify the end of colonialism. This highlights the impact that cricket can have beyond just winning games.

These were the consequences. Right from the beginning, Worrell and Australia’s forward-thinking captain Richie Benaud joined forces to imagine a series that would invigorate Test cricket and break free from pessimism, aligning with the spirit of the game he had learned in Barbados. He was convinced that Hall’s speed, combined with the brilliance of Sobers and the skill of Rohan Kanhai, would make it possible.

Hall’s impressive 21 wickets during a monumental few weeks solidified his legendary status. Even in the intense environment of Australia, Wes Hall refused to bowl short at lower-order batsmen. “I am not afraid to play aggressively, but I will always play fairly,” he confidently states in the present tense.

During a cricket match, Seymour Nurse was positioned at silly mid-off while the opposing Australian team was batting. Our team had them in a difficult situation with only two players left. I bowled a ball that I believed was a leg before wicket (lbw), but that ended up not being the case. In the following over, Garry Sobers caught a ball but was unsure if it was a clean catch or a bounce catch. Seymour then approached me and suggested throwing a bouncer to the last player, whose name I cannot recall but did not think highly of. I questioned the idea of throwing a bouncer at a No.11 player and asked Seymour where he would be fielding. He replied with silly mid-off. I instructed him to defend any hits from the player, pick up the ball, and follow his suggestion to hit the player. However, Seymour claimed he could not do that, to which I responded, “There you have it!”

Australia emerged victorious with a 2-1 score, but cricket was the ultimate winner. Worrell’s foresight had been realized. As the team prepared to leave, having made what CLR James deemed a significant “public entry into the community of nations”, a staggering 250,000 Australians gathered to bid them farewell. And this was no fleeting event: when Hall returned a year later to play for Queensland as part of Worrell’s plan, he was met by a welcoming crowd of one thousand at Eagle Farm airport.

after newsletter promotion

T

In 1963, the West Indies’ tour of England was a highly anticipated event. According to James, following England’s lackluster Ashes tour in 1962-63, there were concerns about the future of Test cricket and whether the West Indian team could replicate their success in Australia.

During Worrell’s final tour as captain, his team won 3-1 in a remarkable series. Sobers was dominant and Dexter was also impressive, with the only drawn game at Lord’s possibly being the highlight.

The last day is steeped in its own legend. After a morning shower, England had to resume their game with 118 runs left and only seven wickets remaining. Hall continued to bowl for the entire match, without any changes for four hours, keeping all four potential outcomes open until the final over. With just two balls left, England had nine wickets down and were six runs away from victory when Colin Cowdrey, with a broken arm from a Hall delivery earlier in the day, took position at the non-striker’s end. Despite the tailender David Allen giving up on the chase, he managed to defend Hall’s final two deliveries and secure a draw.

In the final innings, Hall bowled 40 overs and had a record of 4-93. He ran 35 yards to the crease for each delivery. Even though Worrell motivated him, Hall was easily convinced. According to Baksh in Son of Grace, Hall’s exceptionally long spell may have been the perfect illustration of a person pushing themselves beyond their own limits for the sake of their role model. It was an extraordinary display of physical stamina. It was believed that Hall never quite regained his ability as a bowler after that.

His final actions as a member of the West Indies cricket team continue to bother him slightly. During a tour of India in late 1966, Hall injured his right knee after slipping on a wet outfield in Kolkata. He struggled through the remaining Tests with a decrease in his pace, signaling the start of his decline. Reflecting on this, he recalls being told he was not fit, despite never leaving the field in his 13-year career. He acknowledges that he may not have been the fittest player, but compares himself to others who were allowed to continue playing. Looking back, he believes the only issue was his reduced number of wickets in the last few matches. Despite saying all of this with a smile, it still stings.

During the Kolkata Test, there was a certain eerie atmosphere. Worrell, who was no longer playing but still part of the team, expressed feeling exhausted and unwell. He did not communicate this to the players, who witnessed him give a remarkable and inspiring speech at an official event, as described by Hall in his book Answering The Call.

This would mark his final time appearing in public. Worrell returned to Jamaica and immediately went to the University Hospital, where he was diagnosed with leukemia. When Hall visited him, he was already aware of his condition. On March 13, 1967, Frank Worrell passed away at the age of 42. This occurred just four months after Barbados gained independence as a nation.

In his later life, Hall lived fully and devotedly. He had a transformative experience at a church in Miami in the late 1980s, causing his life to take a different direction once again. Upon finishing his theological studies, he became a minister in 1998 and one of his initial duties was to provide counseling to the inmates at Glendairy, the prison in Barbados near his childhood home. He also made sure to bring Desmond Haynes along to assist with coaching cricket.

S

Sitting in this temporary green room with some of his colleagues, it doesn’t seem like the appropriate moment or location to dwell on the current condition of West Indies cricket, but it cannot be overlooked. He lets out a deep breath. “I am a West Indian through and through.”

He maintains his optimism, stating that the West Indies have always produced top players. He acknowledges the current state of cricket, including Test cricket, ODIs, and the last format. His eyes communicate the rest of his thoughts. He shares his fondness for the sport but also acknowledges the financial aspect. He explains that if a player reaches the top ranking after five or six years of playing and is very skilled, they won’t have to work again. It’s evident that money has not been a top priority for Wes Hall.

I approach him to inquire about his greatest source of pride, and he responds before the question is fully posed. He expresses, “It was truly significant to see West Indians from the working class achieve success on a global scale, no matter where they went. I must admit, it’s a shame that not all of them have written books! They were truly exceptional players, considered icons by many. However, what made that team special was that there were no egos or individuals who thought they were superior to others.”

Ultimately, the main inquiry remains: who comprises Wes Hall’s ultimate West Indies fast bowling lineup? Four legendary players, spanning various eras. Four individuals. Let’s hear it. He takes a moment to collect his thoughts, his arm still propped on the back of his seat. “I thought you were suggesting that you would only choose three more…”

We prepare to leave. His next group of spectators is ready. I can’t help but mention my father, who still reminisces about his day with Wes, Charlie, and Garry at The Oval in 1966. “You see,” he says, “I believe that people admire cricketers for their character. It’s not just about their statistics – 200, 300, 800, or whatever it may be… It’s about the emotions they evoke.”

Great players will be remembered by people, but those who made them feel good will be truly remembered.

Source: theguardian.com