“K

A man named Amanzi, who was the sub-chief, arrived to take away the children of a small village in Rwanda before the second world war. The children were needed to pick flowers for the colonists, known as the Bazungu. The villagers tried to hide their children, but the sub-chiefs, who were wearing sunglasses, watches, and shoes, punished the fathers and forced them to work in the mines. The farmers neglected their own crops in order to grow beans for the miners, and their cattle were taken away. The situation continued to worsen until the village was hit by the worst catastrophe of all: the Ruzagayura famine. The villagers were not prepared for this, as they had no cattle or food stores. They prayed for rain from their god Kibogo, but it did not come. When it finally did rain, a destructive storm destroyed the soil and crops.

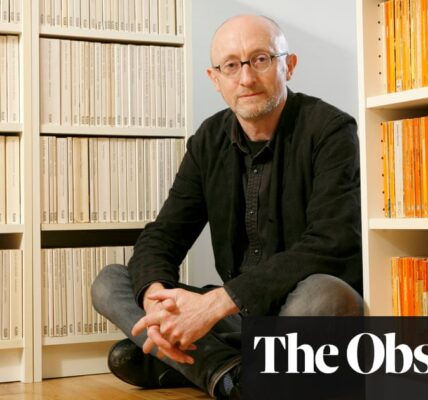

We have only read four pages so far. This quickly paced and concise novel, written by Scholastique Mukasonga, is the newest addition to her published works in Britain. Her previous writings, which include memoirs and fiction, reflect on Rwanda’s tumultuous past. In Kibogo, she delves into the themes of forgetting and remembering, as well as the pervasive impact of Christianity in Rwanda.

The narrative is divided into four sections. In Ruzagayura, the residents, struggling with a famine, revert to their traditional customs and remember how their ruler and the rainmakers were responsible for bringing rain. Four elderly men attempt to recollect the myth of Kibogo, but disagree on the specifics. They search for someone who may have more information, leading them to a female wise woman, Mukamwezi, who claims to be Kibogo’s bride. Mukamwezi was once a member of the royal court. When the king was overthrown by Belgian colonists, she chose to live alone and reject all suitors. She agrees to perform a ritual to beseech Kibogo for rain.

On the lower part of the hill, the Catholic priest, known as “padri”, intends to request divine intervention for rain by leading a procession with a statue of the Virgin Mary to the top of the hill. When rain eventually falls, the padri claims credit for it. He declares the four elderly men as non-believers. As time passes, three of them pass away and, despite objections from the padri, the villagers who claim to be Christian construct shrines in their honor.

After some time, a young and perhaps not very intelligent seminarian named Akayezu, also known as “small Jesus”, appears. He is dressed in white robes and attempts to feed hungry villagers with only two loaves of bread, almost getting trampled in the process. When he miraculously resurrects a child, he gains a following of women and clashes with church authorities. Gradually, he becomes more bold in challenging the priests, questioning why the Bible does not mention black people or Rwandans. He is certain that the story told in the Bible is not about the Jews or even Jesus, but about the Rwandan people.

Akayezu chooses to spread the teachings of Mukamwezi, but ultimately becomes influenced by her. She invokes memories of the stories he was told as a child while sitting at his mother’s feet. “Who will you trust? The words of the priest or the tales your mother shares in the darkness? And you, women, who will you believe: the lessons taught in Catechism or the revelations of the spirit of Kibogo?”

African clergy in colonized African countries started to reinterpret biblical stories for political purposes, in order to gain supporters and resist colonial rule. In this way, Mukamwezi and Akayezu retell the story of the Resurrection, with Kibogo as the main character. Mukamwezi proclaims that Akayezu will be the messenger who will bring back Kibogo and become the next king, saying “You will drive out the priests and all the Europeans.”

Through cleverly written sentences, skillfully translated by Mark Polizzotti, Mukasonga shares the experiences of the villagers as they encounter various visitors with their own agendas. These include an agronomist who criticizes their method of intercropping and insists on planting in straight rows, soccer scouts, NGO workers, and missionaries who destroy a sacred grove to erect a statue of the Virgin Mary. The villagers also fabricate stories of human sacrifice to entertain an anthropologist, who sees potential in publishing these tales. Gasana, the storyteller, proudly declares that his version will be written down and stand the test of time.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

The fluctuating patterns of spoken storytelling are incorporated into a meticulously organized novel. Each of the four sections overlap, retelling the same story from varying points in time and perspectives. This pays homage to the enduring power of oral tradition, which thrives due to its flexibility and adaptability. As the villagers weave together the tales of Kibogo and Akayezu, Mukasonga writes: “And occasionally, a young girl, forgotten at the feet of the storyteller, who refused to fall asleep like the others, stored away in her mind, without fully understanding them, the magical words of the fable.” Reading Kibogo transports one into the magic of this charming and thought-provoking miniature masterpiece.

Source: theguardian.com