David Kynaston’s “A Northern Wind: Britain 1962-1965” explores the theme of finding cheerfulness amidst the gloom in post-war Britain. This review delves into the book’s insights and observations.

O

On the afternoon of Saturday, October 27, 1962, 19-year-old Juliet Gardiner was sitting in her local launderette, feeling terrified as she read the news about Soviet ships approaching the US blockade near Cuba. She couldn’t help but wonder why she bothered with washing her knickers, pillowcases, and tea towels when the world seemed to be on the brink of a nuclear disaster. This moment is highlighted in David Kynaston’s latest installment of his history of postwar Britain, Tales of a New Jerusalem, showcasing his ability to simultaneously capture both the big picture and the small details. With a keen yet empathetic perspective, Kynaston delves into public records and personal diaries, political speeches and television interviews, creating a vivid mosaic of the grand and the intimate.

The potential disaster was avoided and laundromats were temporarily safe, but there are more problems on the horizon during the tumultuous time period being discussed. Many of these issues have eerie similarities to our current situation. The ruling Conservative government had been in power for 13 years and was facing major humiliation due to a scandal (Profumo instead of Partygate), while the opposition Labour party, led by Harold Wilson, was in a strong position for the next general election. France rejected the idea of Britain joining the EEC, deeming them too isolated, and De Gaulle closed the door on negotiations with Prime Minister Macmillan. The PM’s statement in 1957 that “we’ve never had it so good” was being called into question as the north-south economic divide continued. Despite some improvements, poverty was still rampant and those responsible for upholding the welfare state were not always reliable in determining who needed assistance the most. In sum, “Victorian values” were still present. The state of the railway system also mirrored present-day issues, as one-third of the network was on the brink of being dismantled due to Beeching’s cuts, resulting in over 2,000 station closures and once-thriving industrial towns being left behind. In Bristol, a boycott erupted when the city’s bus company refused to hire minority ethnic employees, one of many racial tensions that arose in the early 1960s. Kynaston highlights prejudice and cowardice at all levels of society.

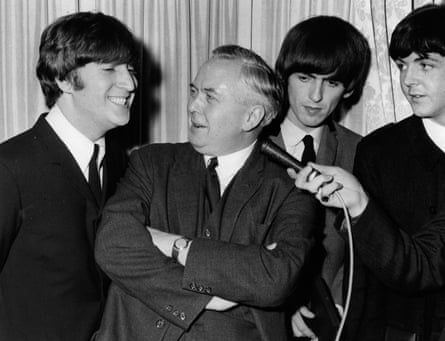

Happiness occasionally breaks through the darkness, although it is often tinged with sarcasm. On television, which was becoming a popular medium, shows such as The Likely Lads and That Was the Week That Was were gaining a following. Soon, Doctor Who, Ready Steady Go!, Top of the Pops, and Match of the Day (which aired from Anfield where Liverpool beat Arsenal 3-2) would make their debuts. In 1963, Alf Ramsey, the new England manager, predicted that the country would triumph at the World Cup in three years. During the week that Joan Littlewood’s satirical revue Oh, What a Lovely War! premiered in Stratford, London, the Profumo scandal was exposed, causing Philip Larkin to share the latest joke with Monica Jones in a letter: “Christine Keeler’s newspaper order? – one Mail, one Observer, and as many Times as possible.” However, the most significant sound heard from these pages is the music of the Beatles, and the screams of teenage girls wherever “the Fabs” made an appearance. Kynaston’s own obsession with the band is evident: in the index alone, there are 23 references to them (compared to nine for Macmillan and four for the Stones), with his passion for their music being a prominent theme among the diarists (“the songs were somehow so moving”).

Reasonably speaking, it is helpful in alleviating a rather disheartening atmosphere that often pervades the book. Despite the prevalent talk of ambition and prosperity during the era, A Northern Wind serves as a chilling reminder of disastrous social management, particularly in the replacement of sturdy Victorian houses with high-rise apartments. Kynaston mentions that even at that time, there were doubts about this modernist ideal, which focused on style and impact rather than the needs of potential tenants. There was also little to celebrate in education, where the ongoing inequality of the 11-plus exam, the unattractiveness of secondary schools, and the “barrier to democracy” presented by private schools kept British society in a state of ignorance. As Kynaston puts it, “ultimately, this was a matter of social class.” This was true even in the 1960s, a conservative era that was still bound by deference at one end of the class spectrum and complacency in its privileges at the other. The film Billy Liar (1963) is highlighted as a significant film of the time, a passionate response to the forces of northern “prejudice, intolerance, and prudishness”, with characters like Billy ultimately condemned to become just as inward-looking as their parents by rejecting opportunities to escape. In the end, it is Billy’s girlfriend Liz (played by Julie Christie) who breaks free, serving as a rallying call for women, though it took a painfully long time for this message to catch on. However, there were some outliers who showed independence, such as Katharine Whitehorn’s bold columns in The Observer and novelists who accurately reflected society’s mood: “thank god those days are over when a woman’s existence is justified by marriage” (Margaret Drabble).

The book ends with two significant moments, one marking a beginning and the other marking an end. In 1964, Labour’s victory in the election was not as decisive as expected, with only a four-seat majority. This reflected the country’s reluctance towards change. The latter moment was the death of Churchill in January 1965 at the age of 90, which many saw as the end of an era. His funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral brought London to a halt and caused the nation to reflect. According to one journalist, it symbolized the end of Britain’s greatness, while another referred to it as a display of self-pity. An elderly diarist described it as sobering, but also noted that Britain has been declared dead before and has always managed to rise again. Kynaston’s writing style is characterized by his ability to present contrasting perspectives and find a way to reconcile them. He is known for his compassionate and unbiased portrayal of our history, making him the most qualified to continue telling this captivating national story.

This piece was revised on October 31, 2023. A previous edition stated that the report of Soviet ships approaching the US blockade around Cuba was on October 27, 1963, rather than 1962.

-

David Kynaston’s book, “A Northern Wind: Britain 1962-1965”, is available for purchase at Bloomsbury for £30. To help support the Guardian and Observer, you can order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Additional delivery fees may apply.

Source: theguardian.com