Was a warm ocean event responsible for the deaths of 7,000 humpback whales due to starvation?

I

In 1972, an event occurred where a humpback whale, who was given the name Festus, was first seen near the mountainous coastline of southeastern Alaska. For 44 consecutive years, this whale would come back every summer, bringing joy to whale enthusiasts, locals, and scientists as it ate in the chilly and nutritious North Pacific waters before migrating to Hawaii for winter breeding.

However, in June 2016, Festus was discovered deceased in Glacier Bay National Park, floating in the water. The leading factor contributing to Festus’s death was starvation, which experts believe was a result of the most severe marine heatwave ever recorded. A recent study, released on Wednesday by Royal Society Open Science, reveals that the humpback whale population in the North Pacific has decreased by 20% from 2013 to 2021, as warmer water disrupted the ecosystem.

According to Ted Cheeseman, a biologist from Southern Cross University in Lismore, Australia who conducted the study, the marine heatwave between 2014 and 2016 significantly decreased ocean productivity and severely affected humpback whale populations.

The North Pacific humpback whales, known for their beautiful songs and impressive breaches, have a maximum weight of 40 tonnes and can grow up to 17 meters long. However, their population was almost wiped out due to extensive hunting over the course of centuries. In 1976, it was estimated that there were only 1,200 to 1,600 humpbacks left in the North Pacific.

Following the International Whaling Commission’s ban on commercial whaling in 1982, there has been a significant increase in the humpback whale population. According to a recent study, there were approximately 33,500 humpbacks in the North Pacific in 2012, with an average growth rate of 6% between 2002 and 2013. This positive trend continued for 40 years and resulted in the removal of humpback whales from the US Endangered Species Act in 2016.

In the year, there was a notable marine heatwave in the north-east Pacific that continued to raise water temperatures. Between 2014 and 2016, sea temperatures were significantly higher, reaching 3-6C above the usual average. As a result, there were fewer nutrients available for phytoplankton, which serve as the foundation of the marine food chain. This led to a chain reaction of effects on the ecosystem, resulting in a decrease in food for various marine species, including sardines, seabirds, and sea lions.

Between 2013 and 2021, a recent research has revealed a concerning decrease in the humpback whale population in the North Pacific, with approximately 7,000 individuals gone missing. This decline is believed to be caused by a shortage of food sources. According to Cheeseman, this significant mortality event is out of the ordinary for humpback whales, who are adaptable and can adjust their diet from krill to herring or anchovies to salmon fry. However, a decrease in the overall productivity of the ecosystem greatly affects their survival.

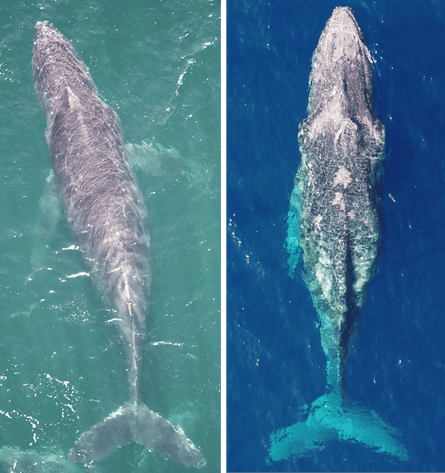

Extended periods of hot weather can result in malnourishment for marine creatures such as whales, as seen with Festus. This can also cause what is known as “skinny whales”, according to Cheeseman. Instead of their typical rounded appearance, these whales have an unbalanced, sharp appearance. Skinny whales are at a higher risk for illness while thin female whales are less likely to give birth.

A study of humpback whales in Antarctica revealed that warmer ocean temperatures lead to reduced food availability, resulting in lower pregnancy rates. Ari Friedlaender, an ecologist at the University of California Santa Cruz, conducted the Antarctic research and was not involved in a separate study on humpback whales in the North Pacific. Friedlaender suggests that the 2014-16 marine heatwave likely influenced the pregnancy rates and may have also contributed to the deaths of some whales in the region.

The results of extended studies of humpback whales in the Au’au channel, located between Maui and Lanai, have shown similar trends. The frequency of mother-calf interactions in this area has decreased by approximately 77% from 2013 to 2018, indicating a significant decline in the reproductive success of humpback whales.

According to Rachel Cartwright, a member of the Keiki Kohola Project in Maui and a researcher focusing on humpback whales, a decline in habitat quality leads to a decrease in carrying capacity. This means that the environment can no longer sustain as many animals. The recent heatwave highlighted the potential impact of nutritional stress on humpbacks and suggests that there will be no return to peak levels in the future.

Over the last twenty years, researchers have been able to easily recognize Festus, a humpback whale, due to the distinctive black-and-white patterns on his tail fluke, similar to a human’s thumbprint. To determine the population of his species in the North Pacific, Cheeseman and his team utilized the largest database of individual photo-identification for a whale species known as Happywhale. This database includes hundreds of thousands of images of humpback tail flukes from 46 research organizations and over 4,000 citizen scientists from various countries.

In 2015, Cheeseman established Happywhale with the goal of developing a dynamic collection of data to facilitate the examination of crucial questions regarding the well-being of the ocean and its inhabitants. He refers to this online database as the “Facebook for whales,” as it utilizes comparable technology for recognizing images. With contributions from members of the community and numerous scientists around the globe, Happywhale has a 97-99% success rate in identifying humpback whales and is additionally employed to monitor a variety of other marine species.

Martin van Aswegen, a PhD candidate at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, has been utilizing unmanned aerial vehicles to research humpback whales that are native to Hawaii. For the past six years, Van Aswegen has determined the measurements and weight of over 7,500 whales by tracking them from their breeding location in Hawaii to their feeding location in southeast Alaska. He relies on the Happywhale database to identify the whales he observes.

Van Aswegen reports that the shortage of food during the marine heatwave ultimately led to reproductive failure in 2018. Out of the humpback calves making the journey from Hawaii to Alaska, only three survived, and they were all missing by the end of the feeding season.

In 2021, a brief and intense warm period in the North-East Pacific was observed to have affected the feeding habits of marine mammals. According to Van Aswegen’s research, it was found that, on average, 24 female mammals nursing their calves experienced weight loss during this time. This is unusual as these mothers typically gain around 16kg per day during the feeding season. Van Aswegen stated, “It is unprecedented for lactating females to lose weight while on their feeding grounds.”

According to Lars Bejder, the director of Marine Mammal Research Program at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and co-author of a recent study, ongoing efforts like using drones to measure humpback whales and obtaining tail fluke images through Happywhale are extremely important. They provide valuable insight into the impact of major oceanographic events. Bejder believes that a healthy ocean is essential for the well-being of whales, and by monitoring these animals, we can keep track of the health of our oceans.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on X for all the latest news and features

Source: theguardian.com