Many are profiting from credit schemes, but the destination of the money remains uncertain. These individuals, known as “carbon cowboys,” are making large sums of money.

I

The villages in the districts near Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe may be unaware that they were the focus of a lucrative carbon industry. The Miombo woodlands that dominate the area are primarily occupied by small-scale agricultural workers and consist of straw and mud dwellings. The roads are rough and rarely used by cars, while access to healthcare and internet services are limited. While information on the area is incomplete, research shows that Hurungwe district, which encompasses several villages, has a poverty rate of 88%.

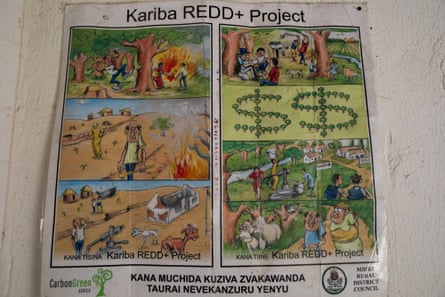

These regions are part of the extensive and profitable Kariba conservation initiative, which covers an area almost equivalent to the size of Puerto Rico. It is one of the biggest forest offsetting programs approved by Verra, the largest certifier in the world. Since 2011, this project alone has earned over €100m (£85m) in revenue by selling carbon credits, which is equal to Kenya’s projected national emissions in 2022, to western companies. According to now-deleted data published by the project developer, proponents argue that these schemes provide a swift way of transferring billions of dollars in climate and biodiversity financing to the developing world through company pledges.

After over ten years since the project began, locals are disappointed that the promised projects and infrastructure have not materialized. Only a small portion of the €100 million has been given to the villages involved in the project.

“We are not witnessing a flow of money downwards.”

Rogers Kavura, a 46-year-old resident of Chikova village in Hurungwe district, believes that rewards will eventually follow. He recently became a forest ranger through the local council, thanks to funding from the offsetting project.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Kavura states that there are reports of the company’s profit, but the destination of the funds remains unknown. The community is expressing dissatisfaction as they have not witnessed any benefit from this profit.

The organization South Pole, responsible for managing and overseeing the carbon scheme, opted to withdraw from the Kariba project in October in order to learn from their past experiences with the project. This decision came after several reports by Follow the Money, Die Zeit, and the New Yorker uncovered potential issues with financial transparency and undisclosed trophy-hunting activities within the project. This uncertainty has created an uncertain future for the villages and forests in the Kariba area. Furthermore, the carbon market as a whole is facing a crisis after a year of controversies, and there are concerns amongst experts that other carbon schemes around the world may also be abandoned due to evidence that many projects are producing ineffective credits that do not effectively combat global warming.

In this form of carbon offset program, communities should receive compensation – in the form of money or investment in their local infrastructure – for preserving trees. However, in actuality, there are no legally binding agreements for companies that sell offsets to disclose their profits, which are frequently undisclosed by project developers.

A significant portion of Kariba’s €100m revenue has been reduced by the project developers in the form of fees and expenses. Out of this amount, €86m was allocated to costs and profits for the broker and technical lead South Pole, as well as for Carbon Green Investments, the project coordinator. Ultimately, only a maximum of €14m reached the communities of Kariba through cash transfers and improvements in infrastructure.

The Guardian assessed project records, consulted with district council authorities, reached out to Verra, South Pole, and Steve Wentzel, a Zimbabwean entrepreneur who possesses land for the Kariba project and also owns Carbon Green Investments, the firm responsible for distributing the funds. Additionally, a reporter was dispatched to Kariba to conduct interviews and investigate potential projects. Though there was indication that some funds had been given to local communities, our findings revealed that only a small portion of the project’s profits actually trickled down to the ground level.

According to its deleted figures, South Pole made a profit of €18m (£15m) without providing any ground services. This is more than the amount spent on the Kariba project. The Swiss company deducted €24m for expenses and then sent €57m to Wentzel, who received 30% of the revenue, project costs, and funds for local communities.

According to Bigboy Mangirazi, a resident and educator in the region where the carbon project is taking place, the funds have been allocated on paper but have yet to be implemented in reality.

The speaker expressed dissatisfaction with the local chiefs, stating that they have not fulfilled their promises. Despite some small developments, such as an agriculture field and borehole projects, the people are still frustrated and questioning the true benefits of the carbon project.

According to Verra guidelines, which approve most voluntary carbon offsets, project developers are not obligated to reveal or verify the distribution of funds received from credits.

The ‘carbon cowboys’

For companies that traded in Kariba’s carbon credits, however, there is little doubt of the financial benefits generated by the project. During the pandemic, prices for forest carbon credits rose dramatically, from less than $1 a tonne to more than $30 a tonne (78p to £23.30) for some schemes. In the process, projects like Kariba were transformed from struggling conservation schemes into financial assets worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The credits have been traded by a growing number of carbon desks at investment banks and oil companies at lucrative premiums.

Professionals state that the example of Kariba serves as evidence of larger problems within the industry, where projects to preserve forests tend to favor international traders rather than local communities.

Display the image in fullscreen mode.

According to Elias Ayrey, a remote-sensing forest scientist and owner of Renoster, a company that evaluates carbon projects, nature-based carbon markets are now dominated by what the industry calls “carbon cowboys”. These groups have been actively acquiring and including large portions of land in the developing world without regard for Indigenous rights or compensating local communities for their efforts in conservation. Ayrey publicly raised concerns about this issue a year ago.

He calls Kariba “a textbook example”. “Them walking away from the project is an abandonment of the commitments that they made at the start … to ensure that the trees remained intact for 30 years and that local people benefited from the work,” Ayrey says.

There are widespread concerns surrounding the issue of “carbon cowboys” and the management of carbon projects. Beyond the Kariba area, there are worries among insiders that organized crime and money laundering may have seeped into the carbon markets, where large sums of money can flow through with little regulation. In certain projects, individuals have been displaced from their homes. In one case, there have been allegations of widespread sexual abuse despite claims of supporting local women. In other instances, project developers have made promises to establish land rights or provide benefits to the community, but have ultimately failed to follow through.

According to Senior Researcher Luciana Téllez from Human Rights Watch, it is a common practice for developers of carbon offsetting projects to make bold claims that the main beneficiaries of their initiatives are local communities and Indigenous peoples. However, these assertions are often difficult to verify due to the lack of transparency surrounding the projects’ finances. Usually, only the companies in charge of the projects have access to information on the amount of money being distributed and how much profit their executives and business partners are making.

She adds: “The standards for certification in the voluntary carbon market do not mandate developers to fairly distribute profits with communities where the project is located. Currently, there is a lack of transparency regarding project revenues, which makes it difficult to verify the claims that these projects significantly benefit indigenous peoples and local communities.”

Following investigations by the New Yorker and Follow the Money, Renat Heuberger, the CEO of South Pole for many years, resigned after the Kariba project came under scrutiny and South Pole withdrew from the project. The company declined to comment to the Guardian about the project, but referenced two earlier statements supporting the success of Kariba in utilizing carbon markets and its positive impact on the community. South Pole stated that the distribution of funds from the project was not within their purview and revealed plans for changes within the senior leadership team in 2024.

Mr. Wentzel, the proprietor of Carbon Green Investments, has been under heavy scrutiny for his handling of finances and record-keeping on a specific project. Ultimately, he managed to furnish the Guardian with internal records detailing the distribution of €14 million, which included thorough receipts and invoices for approximately €4.5 million of the total amount. He has also voluntarily initiated an audit with Deloitte.

Display Image in Full Screen View.

According to Wentzel, gaining first-hand experience and comprehending the associated expenses and difficulties is crucial. Even though Kariba Redd+ has been in operation for 12 years, it remains the sole project of its kind in Zimbabwe, showing the lack of feasible options or investor attraction. The country’s distinctive economic situation over the past 22 years cannot be compared or aligned with traditional guidelines. Wentzel also mentions that the project would have to continue selling carbon credits to sustain itself.

Another topic of discussion is whether the businesses who purchased offsets from the unregulated market actually achieved the promised environmental impact. According to Renoster’s analysis, the project has greatly exaggerated the threat to the forest. The approach used to produce the credits has now been terminated by Verra.

Verra has stated that it is unable to provide comments on numerous concerns regarding Kariba at this time due to an ongoing review; however, it acknowledges that Kariba may be an exception.

A spokesperson states that Kariba stands as a unique case in the extensive history of influential Redd+ projects globally. Other projects registered with Verra have successfully preserved forests, providing a vital solution for mitigating the severe effects of climate change.

Display the image in full screen mode.

According to Verra, individuals leading a project may face suspension if they engage in wrongful or unlawful actions. The organization is currently considering ways to address reported concerns regarding the environmental credibility of the Kariba carbon credits. It emphasizes that its carbon standard prioritizes the protection of the environment and the well-being of local communities.

A teetering market

The Kariba mega-project is not the only one facing uncertainty. A recent investigation by the Guardian revealed that over 90% of offset projects may end up being valueless. Numerous rainforest offset projects, including some of the largest ones, have been found to produce a significant number of worthless credits, as per the analysis conducted during the investigation. In an effort to address this issue, Verra is implementing reforms and introducing new regulations for multiple projects. However, these changes may put projects like Kariba in a difficult position if they receive fewer credits under the updated system.

In November, Ecosystem Marketplace reported a sharp decline in the value of the carbon market, dropping from over $2 billion in 2021 to $343 million in year-to-date data for November 2023. There is also increased scrutiny on companies’ claims of offsetting carbon emissions.

The company Delta, currently facing a lawsuit in California for falsely claiming to be “carbon neutral,” has halted their purchase of carbon credits. Delta vehemently denies the allegations. According to Bloomberg, other companies such as Barclays, L’Oréal, and McKinsey have either exhausted their Kariba credits or have no intention of purchasing more. The United States’ climate representative, John Kerry, believes that the voluntary carbon market has the potential to be “the biggest marketplace the world has ever seen,” but there is currently limited progress towards this goal in the near future.

According to Libby Blanchard, a researcher at the University of Utah and co-author of a UC Berkeley report, forest protection projects do not always result in mutual benefits, despite being promoted as such by developers. In fact, when they are over-credited, these projects can cause imbalances and have negative effects for certain parties involved. The September report highlighted various concerns and challenges within the offsetting system.

“She believes these examples give the impression that forest protection initiatives are solely for the benefit of developed countries rather than genuine efforts to intervene.”

During the Kariba project, the developers profited greatly and emerged as the winners. However, the individuals whose lives were impacted by the project, and who are not to blame for climate change, were unable to benefit from these funds. As a result, the forest and biodiversity also suffered losses.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on X for all the latest news and features

Source: theguardian.com