I

If the Labour party gains control of the government, as indicated by polls, it is imperative that they offer the private sector appealing incentives to increase investment in Britain’s economy. This will improve productivity and promote environmental sustainability. Just as Joe Biden has successfully implemented in the US, there is potential for Keir Starmer to do the same in the UK.

The process of changing the economy will require a significant amount of money. Additionally, this cost is increasing and may be more than what Britain and the EU can afford.

Private companies are offering money, as there is a surplus of cash in the world seeking investments. The desire for high returns is causing a financial barrier to necessary improvements in UK infrastructure, such as hospitals and the electricity system.

Biden is discovering this fact. His Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which serves as the primary means for promoting a shift towards lower-carbon energy consumption in the US, coincides and intersects with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Chips and Science Act. These laws aim to bolster the US semiconductor industry at an estimated cost of $2 trillion over 10 years.

The subsidies and tax breaks for IRAs, which were initially predicted to be $385 billion, could potentially reach $3 trillion if the US successfully meets its goal of reducing emissions from the electricity industry to 25% of the 2022 total. Some analysts believe this could happen.

The EU has created a fund called NextGenerationEU worth £600bn in order to compete with the US initiative and support the green and digital transitions. Although the amount seems significant, it is divided among 27 countries and may require additional private funding to reach its goals.

The United Kingdom is using an incremental method by offering individual subsidies totaling a few billion pounds. In comparison, the Labour party’s green investment fund of £28bn is greater, assuming it is not reduced further before the election, and is built upon a more organized industrial strategy. However, it still appears insignificant when considering the global scale.

That leaves the shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, like all her counterparts in the industrialised world, needing huge amounts of private capital to get investment moving.

The requested subsidies from the owner of British Steel, China’s Jingye Group, and the owner of Port Talbot steelworks, Tata, to transition from coal to electric furnaces have been staggering. This provides a glimpse of what is expected in the future.

Green bonds and infrastructure bonds, which generate money for projects that aim to reduce emissions, are seen as a significant funding source, but have proved to be very expensive and the price is likely to stay high, limiting their attraction.

London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, has suggested a potential solution that is expected to gain more traction in governmental circles: providing credits in exchange for environmentally-friendly initiatives from private companies.

The London climate resilience review, written by Emma Howard Boyd who previously led the Environment Agency, proposes a potential solution for generating investments in the city. In a preliminary report released last week, she recommends providing credits to interested parties, such as private landlords, local governments, and utility companies like Thames Water, if they perform necessary actions at their own expense to decrease the amount of impermeable surfaces that contribute to flooding.

These credits have the potential to endure for many years and can be utilized to counterbalance the negative actions of the buyer, such as the carbon emissions produced by their business, in their efforts to reach net zero.

Carbon credits have been around for some time and are not uncontroversial. The credits are based on markets that critics say price them too cheaply, meaning large industrial firms can afford to buy them and carry on much as before.

Howard Boyd suggests implementing measures to prevent exploitation of credits associated with infrastructure undertakings in London. Additionally, she proposes conducting additional investigations on “financial models that foster investment opportunities in nature-based solutions”.

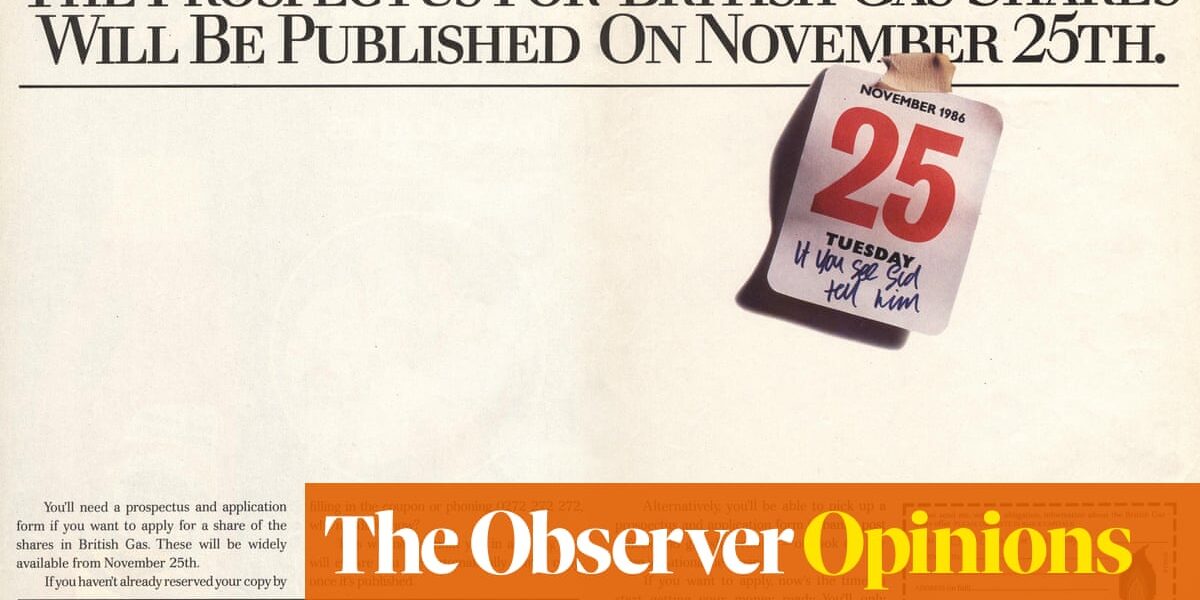

During the 1980s, the UK generated income by selling numerous state-owned assets at significantly reduced prices. These assets included North Sea oil and gas rights, British Telecom, BP, and British Airways. In the following decade, the rail network and National Grid were also privatized. The Blair government, recognizing that many valuable assets had already been sold, shifted its focus to the future by auctioning off licenses to mobile phone companies and entering into long-term contracts such as the controversial private finance initiative.

Due to the influence of established political agendas and the limitations of state borrowing, there is now a smaller amount of government funds available for use. This has prompted politicians from all parties to explore creative methods of generating revenue.

Using infrastructure credits may be a potential solution, but they cannot hide the significant amount of work that must be done in order to achieve net zero, whether it be today or tomorrow.

Source: theguardian.com