Can we use satellites to track biodiversity, similar to how we monitor weather patterns?

F

For the small number of individuals who are able to view Earth from outer space, the effect is frequently significant. Known as the “overview effect,” astronauts have described feeling deeply affected by the experience, as they gain a clear understanding of the planet’s delicate nature and stunning appearance. Some, like actor William Shatner, have even expressed being overwhelmed with sadness.

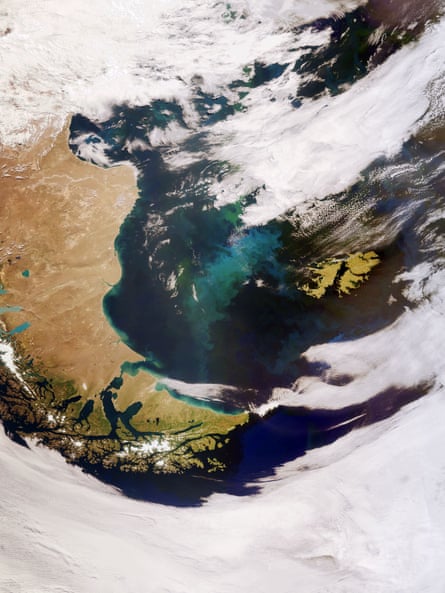

Scientists are suggesting the development of a fresh system that could utilize observations from space to revolutionize our comprehension of the Earth’s evolving ecology and intricate systems.

Scientists propose a new global program that integrates satellite data and imagery with various on-the-ground technologies, including camera traps, acoustic monitoring, and DNA barcoding. This program aims to monitor the health of the planet and protect essential resources for billions of individuals by collaborating with every country in the world.

In 2022, governments made a promise to change their connection with nature by the end of the decade. They committed to 23 targets in order to prevent human actions from causing extinctions and to restore 30% of the Earth’s damaged ecosystems, in an effort to stop the rapid decline of biodiversity.

However, a increasing amount of scientists are cautioning that the information regarding the well-being of Earth’s oceans, soils, forests, and species is deeply flawed, making it difficult to determine if we have achieved our agreed-upon goals. While there have been significant developments in monitoring the climate, data on biodiversity is lacking in comparison. To address this problem, researchers have suggested implementing a new system for monitoring the biosphere, similar to how we track weather patterns, in order to regularly assess the health of the planet.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Several countries, including Canada, Colombia, and various European nations, are creating their own biodiversity observation networks, commonly referred to as BONs. Experts suggest that these networks should be integrated into a global observation system. A BON system gathers data on oceans, soils, forests, and species to provide an assessment of a country’s biodiversity status, which could then be merged on a global scale.

According to Andrew Gonzalez, a conservation biology professor at McGill University and co-chair of GEO BON, a global network focused on observing biodiversity, the level of uncertainty in our understanding of where biodiversity is changing is too high. Even if we are able to reach our goals, it would be difficult to accurately measure them.

“The success of hitting the target remains unknown. I am uncertain if everyone is prepared to accept this harsh truth,” he states. “As the saying goes, without proper measurement, management is impossible. Furthermore, without prediction, protection is not possible. These factors hold significant importance.”

This year, international space agencies are collaborating to enhance their monitoring of biodiversity. Researchers have identified several limitations in the current data. A recent analysis of 742 million records from 375,000 species in 2021 revealed significant gaps and biases, with only 6.74% of the Earth’s surface being sampled. The highest elevations and deep sea areas have particularly low levels of data. The tropics, despite being home to a vast amount of biodiversity, have some of the largest gaps. The majority of records (82%) come from Europe, the US, Australia, and South Africa, with over half of them focused on less than 2% of known species.

In 2023, Kew Gardens discovered 32 areas of the planet, referred to as “dark spots,” that have insufficient data on plant life. These regions, such as Fiji, New Guinea, and Madagascar, are known to have abundant plant diversity. However, only one dark spot was located in North America, while fourteen were in Asia’s tropical region, six in the temperate region, nine in South America, and two in Africa. These data gaps are not limited to only animals.

According to Alice Hughes, a professor at the University of Hong Kong, inadequate data coverage has hindered our understanding of places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite being home to a significant number of species and having the second-largest rainforest on Earth, it remains poorly studied and under threat. Hughes suggests that geospatial data can aid in monitoring loss from these areas, but advancements like eDNA and other methods offer alternative ways to assess ecosystem health.

Acoustic monitoring and DNA barcoding are additional methods that aid in comprehending ecosystems and identifying countless undiscovered species. Advancements in scanning technology have also made it possible for researchers to survey an entire forest for illnesses and track the distribution of species. However, scientists believe that there is still more work to be done in studying the Earth’s overall systems.

According to Hughes, when visiting a doctor, it is not enough for them to simply observe and comment on one’s appearance such as saying “you look healthy” or “you look pale”. Instead, they should take measurements. This data can be used in various ways, ultimately allowing us to get a better understanding of the state of the planet.

According to Maria Azeredo de Dornelas, a biology professor at the University of St Andrews, we require a larger observation system to monitor biodiversity in a similar manner to how we track weather patterns. While it may not need to be as frequent as weather measurements, it is still necessary.

It is possible to achieve success in this matter. However, it would require collaboration on a global scale as it is not something that one country or continent can handle alone. The Earth’s diverse life forms are not affected by political boundaries.

Source: theguardian.com