Review of “Trailblazer: Jane Robinson, the First Feminist to Transform Our World” and “A Dirty, Filthy Book” by Michael Meyer.

W

Although her name may be difficult to pronounce, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon is a well-known and influential figure in Victorian literary circles. She is often mentioned in books about this time period, as she was a highly respected artist and co-founder of Girton College in Cambridge. Additionally, she was related to Florence Nightingale and a close friend of George Eliot. Despite being a minor character, Bodichon is remembered for her independent and lively personality, which stood out even when the focus was on someone else. She was considered quite progressive for her time, and Eliot even described her as being both cheerful and sharp. In her diary entry from 6 May 1859, Eliot mentions receiving a letter from Bodichon expressing joy over her success and belief that Eliot was the true author of “Adam Bede,” despite only reading excerpts from reviews. While everyone else assumed the novel was written by a man, Bodichon recognized Eliot’s intelligence and unique perspective.

In her new biography of Bodichon, titled Trailblazer, Jane Robinson (author of Bluestockings and Ladies Can’t Climb Ladders) aims to bring Bodichon to the forefront by highlighting her achievements, despite previous biographies being written about her. Robinson argues that Bodichon’s lack of recognition is due to her multifaceted talents. However, even Robinson acknowledges that it is Bodichon’s connections and relationships with notable figures that will capture the attention of modern readers. The book begins with a depiction of a sunflower, with Bodichon’s name at its center and lines connecting her to individuals such as Queen Victoria, Lord Tennyson, and Emmeline Pankhurst.

Her subject’s personal life is also worth mentioning. Despite her contributions to the English Woman’s Journal and the establishment of the first women’s college at Cambridge University, Bodichon’s unconventional marriage to a French doctor who often dressed as an Arab in their second or third home in Algiers is the most intriguing aspect of her story. She also promoted gymnastics for students at the rural college in Hitchin, although not everyone was capable of handling the trapeze.

Bodichon was born in 1827 to an unmarried Norfolk parliamentarian and a Derbyshire miller’s daughter. Sadly, her mother passed away from tuberculosis when Bodichon was only 18 months old. Despite the unconventional circumstances of her birth, Bodichon’s childhood was not secretive or deprived. In fact, she grew up with a sense of freedom and luxury, as her family traveled in a custom-made horse-drawn omnibus equipped with extravagant features such as horsehair sofas and silver door handles. Her father also encouraged her education and, upon her 21st birthday, settled a portfolio of investments on her, ensuring her financial independence. This freedom allowed her to pursue interests such as attending Bedford College in London to study drawing. Even as she became involved in the suffrage and women’s education movements, she maintained her passion for watercolor painting and even exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy. She also had connections with famous artists, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and owned a beloved house in Sussex.

Barbara’s first romantic partner was John Chapman, a publisher and well-known charlatan who is now remembered for his affair with Eliot. His letters to Bodichon, attempting to convince her to engage in sexual activities for the sake of their health, are some of the strangest I have ever come across, even by Victorian standards. I thoroughly enjoyed reading about this part of the book, as well as the section where Barbara travels to Algiers and meets Eugène Bodichon, whom she decides to marry. Their relationship seemed to be quite passionate until his eccentric behavior became too much and she left him to suffer in the heat. However, I also have to admit that I did not appreciate Robinson’s tone in Trailblazer, which I found to be overly cutesy. Instead of her imaginative musings, I would have preferred a straightforward account of Rossetti’s proposal to Lizzie Siddal, which took place on Bodichon’s property.

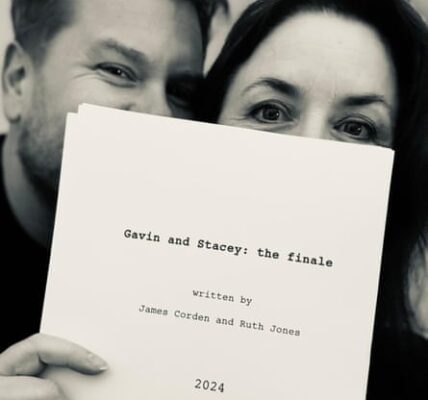

Display the image in full-screen mode.

The issue of tone is also raised in Michael Meyer’s A Dirty, Filthy Book, which chronicles the 1877 trial of feminist free-thinker Annie Besant and liberal activist Charles Bradlaugh for publishing Charles Knowlton’s The Fruits of Philosophy. This manual boldly discussed the basics of contraception to a British public who were largely uninformed about such matters at the time. Meyer, an American author, wants readers to understand the courage of Besant (who ultimately lost custody of her daughter due to the trial’s publicity) and the relevance of her story in the current climate of threats to abortion rights. He even goes so far as to describe Besant as a “badass” and compares her trial to the Sex Pistols’ revolutionary concert at the Lesser Free Trade Hall. While Meyer provides extensive information about Victorian London, he also seems hesitant to believe that the Victorians were vastly different from us today (although I personally believe they were). This leads him to make some peculiar statements, such as suggesting that Besant was drawn to her estranged husband because of his clerical robes.

The trial of Besant and Bradlaugh, overseen by the promiscuous chief justice Alexander Cockburn, is the main focus of Meyer’s book. Despite being verbose, his description is vivid. However, there is not much new information and the focus on the trial may leave readers feeling disappointed. Meyer does not delve into the remaining 56 years of Besant’s life, during which she became a theosophist and moved to India. This raises questions about the significance of the trial for both Besant and others. In comparison, the Chatterley trial in 1960 had a more significant impact. However, reading old sex manuals is surprisingly entertaining. While I am grateful that I don’t have to use sponges and white oak bark like they did in the past, it is amusing to imagine men with mutton chops eagerly consuming spoonfuls of cayenne pepper to boost their energy while wearing long nightshirts.

Jane Robinson’s Trailblazer, published by Doubleday for £25, is hailed as the pioneering feminist who transformed our world. To show your support for the Guardian and Observer, you can purchase your own copy at guardianbookshop.com. Additional fees may be incurred for delivery.

Source: theguardian.com