W

When Caster Semenya, a middle-distance runner from South Africa, won her first gold medal in the 800m race at the Berlin world championships in August 2009, it was met with controversy. Many of her rivals and commentators questioned her physical appearance and dominance in the race, suggesting that she may have a more masculine build.

One month after the event, the findings of a gender assessment she underwent were made public. Shockingly, she learned, along with everyone else, that she had a condition called “differences in sex development” (DSD): her internal reproductive organs were testes instead of ovaries, leading to higher levels of testosterone typically seen in adult males rather than females.

Ever since, her career – which includes three world championships and two Olympic gold medals – has played out in the middle of a legal and ethical maelstrom. World Athletics introduced testosterone limits for athletes with DSD in 2011, and Semenya’s first Olympic title in London 2012 was won while running on hormone suppressants; her second, in 2016, came when the limits were temporarily suspended. Since their reintroduction in 2018, Semenya has fought to have them lifted, losing her case at the court of arbitration for sport (CAS), and recently winning the right to appeal from the European court of human rights.

During races, she never discussed the issue, but during legal proceedings, she spoke with a mix of intensity and composure. In her memoir, she fiercely expresses her emotions. The majority of her frustration is directed towards World Athletics, specifically its president Sebastian Coe, whom she depicts as a “petty man” using moral judgments to elevate his own importance. “Between Sebastian and I, there’s a personal element,” Semenya states. “He has a vendetta against me.”

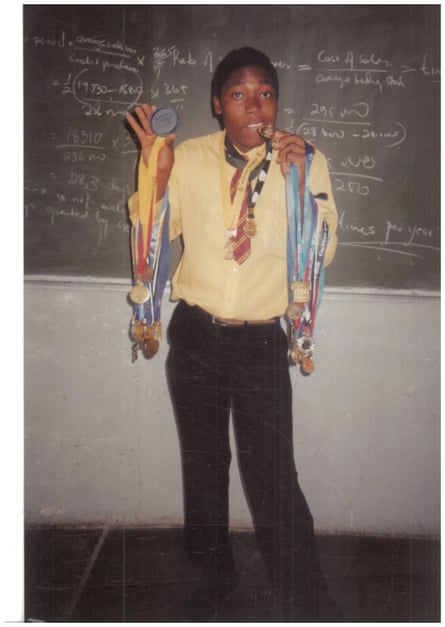

The book presents Semenya’s life as a typical sports biography and focuses on her inspiring journey. However, it evokes a sense of empathy rather than motivation. Even without her later experiences, Semenya’s childhood in a rural Limpopo village in South Africa’s northernmost province would still be touching and enlightening. Despite not being poor, as she clarifies, her family lived in a large home by their standards, with five bedrooms and a living room. However, their way of life was vastly different from that of many readers. They had to fetch water from a communal well, used an outdoor toilet, and did not have access to electricity until 2001. While her father worked as a gardener in Pretoria, 200 miles away for extended periods, Semenya and her five siblings balanced school with helping their mother farm a small plot of land.

Moving moments are depicted without self-pity: a seven-month period spent alone in the hospital after injuring her knee and waiting for surgery; later, being sent away from home to care for her grandmother and male cousins. These childhood experiences shape her character and drive – she claims to have always been determined, and takes pride and joy in her strong, agile body. With a natural talent for football, she dreams of leaving her village to play professionally. She is also the only girl who joins the boys in hunting, starting with rabbits and progressing to more dangerous prey like springboks and warthogs.

In a culture where physical punishment is commonly used as a form of discipline, Semenya defends herself using physical force. She was only six years old when she first fought back against a larger boy. Interestingly, even though she had aspirations of becoming a famous football player, she also dreamed of becoming a soldier, indicating her natural inclination towards confrontation. However, her preference for traditionally masculine traits and behaviors was never seen as a significant issue to her. She states, “we noticed I was different, but different didn’t mean wrong.” Her preference for wearing pants instead of dresses, her deeper voice during adolescence, and her attraction to women were all accepted and not met with shame or exclusion within her community.

The story unfolds when she stumbles upon the world of competitive running. Her physical appearance is questioned by her competitors, and one, who would eventually become her wife, accuses her of being in the incorrect changing room. The most uncomfortable moment occurs in 2009 when Semenya is taken to a hospital in Germany after winning her semi-final at the world championships. There, doctors are tasked with determining her gender. An 18-year-old is presented with a sonogram wand that resembles a “large artificial penis” and she threatens to destroy all the equipment in the room if they try to insert it into her vagina.

The media’s prying and humanity’s biased tendencies do not reflect positively in this situation. Hurtful remarks and deliberate exclusion occur. While hailed as a hero in South Africa, she is also relentlessly pursued. The rejection and mistreatment she faces in her career, as well as the threat to her identity as a female athlete, are magnified by her being a black South African.

Due to her country’s history of apartheid and the objectification of black women’s bodies, it is understandable that she believes there may be a racial bias in how she is treated. She expresses anger and disdain towards the doctors and scientists who have conducted research that has led to her exclusion, describing their methods as “disgusting”, their studies as “completely false”, and their medical treatments as “cruel”.

However, this is just one perspective that has been strongly presented. It may not be evident from this book, but experts from both sides in the court of arbitration for sport hearing have acknowledged that testosterone is the main factor influencing the difference in sports performance between sexes. Additionally, the court’s ruling states that athletes with a condition known as 46 XY DSD, which means they have 46 XY chromosomes, have a notable advantage in sports compared to female athletes with XX chromosomes. This includes having more lean body mass, larger hearts, and higher cardiac output, as well as a larger V0.2

The maximum amount of oxygen that can be delivered to muscles during exercise is known as “max.” The varying development of bodies during puberty makes it impossible for fair competition between the two groups.

The recent ruling on Semenya’s eligibility as a female athlete has also affected other top runners who were assigned female at birth, such as Burundi’s Francine Niyonsaba and Kenya’s Margaret Wambui, who won silver and bronze respectively in the 800m race in 2016. This case also brings attention to the larger issue of transgender women in sports and the potential advantages of those who have gone through male puberty. While Semenya’s successes on the track should be celebrated, there is also a need to protect fairness in women’s sports.

In the beginning of her book, Semenya emphasizes the significance of discussing lines. She states, “We as humans have an obsession with them.” While many are content with following the established line and allowing it to define them and their place, Semenya does not fall into this category. As stated in the CAS ruling, “Natural human biology cannot be perfectly aligned with legal status and gender identity.” The debate on where the line should be drawn in regards to categorizing men and women’s sports is ongoing, but Semenya’s story can remind us to consider the dignity of all competitors involved.

Source: theguardian.com