D

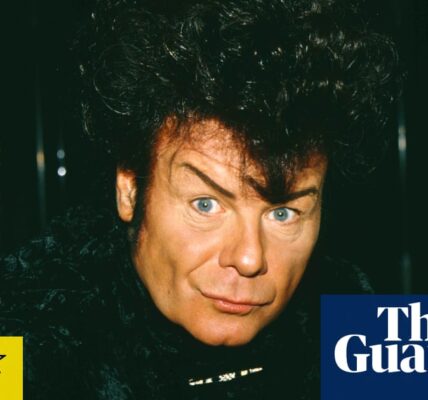

Dutch author Lucas Rijneveld, previously known as Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, received the International Booker prize for their first book, The Discomfort of Evening. The story follows a farmer’s daughter who is coerced into engaging in sexual games with her siblings after their brother’s accidental death. The book includes scenes of stolen vials of bull sperm and the use of an insemination gun. The main character, who is 12 years old by the end of the book, also has fantasies about a local vet who compliments her appearance. Some readers have compared the book to Ian McEwan’s “Ian Macabre” era, but Rijneveld credits the influence of Dutch novelist Jan Wolkers and their own childhood – particularly their experience as a girl – growing up in a Protestant farming family after their brother’s tragic death in a bus accident on the way to school.

Rijneveld’s second novel, My Heavenly Favourite, contrasts greatly with their first book. It follows the story of a paedophile livestock vet who manipulates a 14-year-old girl after her brother’s death in a hit-and-run. The book spans one summer and is approximately 300 pages long, with only 42 paragraphs and minimal punctuation, reflecting the protagonist’s lack of boundaries.

The text describes a series of escalating violations committed by the narrator, starting with inviting the woman to his youngest son’s birthday and culminating in a promise to take her on a road trip to find her estranged mother. This creates a consistently sordid atmosphere, which is not surprising for readers familiar with Rijneveld’s debut. The same grim and dirty tone can be found in scenes where the narrator relieves his thoughts by masturbating into a Mars bar wrapper or a copy of Proust. There is also a hint of dark humor, reminiscent of the author’s previous work, when the narrator’s son begins dating the woman he is trying to manipulate. In one instance, the woman’s father leaves the upkeep of their farm to her brother, who throws a rave where a bull is given MDMA.

In general, this book is very different from Discomfort and cannot be easily confused with a crude comedy. Its writing style, which combines past and present events, real and imagined, fears and desires, creates a dizzying whirlwind that traps readers in a nightmarish vortex. The short chapters, only six or seven pages long, provide a brief respite from this intense experience. One can only imagine how challenging it must have been for Michele Hutchison to translate the book. As the narrator’s own memories of childhood abuse intertwine with his ongoing horror over the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak, his traumatic psyche is also haunted by delusions of the girl who talks to Hitler and Freud and believes she caused the collapse of the South Tower in the World Trade Center.

Part of what keeps you reading – I can’t deny it – is the constant question: “Did I really just read that?” The action accelerates when the increasingly frenzied protagonist exploits the girl’s curiosity about what it’s like to have male genitalia, at first giving her a severed otter penis to hide (and rot) under her bed. But the novel doesn’t rely on the usual attractions of wicked narrators; Rijneveld doesn’t seek to make the vet perversely good company on the page, nor does he deploy unreliability as a kind of reader-reward mechanism as we wise up to the extent of his deceit. Even as expertly timed detonations tilt our understanding of events, darkening the depravity yet further, the book’s real draw lies in its between-the-lines portrait of the pulverising impact of grief on the girl’s family: the pivotal death of their son, referred to only as “the lost child”, represents just one of several lost (stolen) childhoods here, including the vet’s, assuming – the biggest of ifs – we take him at his word.

I was deeply affected by this book, and if you have been following Rijneveld’s work up until now, I imagine it would be even more unsettling. The Discomfort of Evening was written from the perspective of a younger version of the main character in this novel (a girl who is envious of male genitalia, obsessed with Hitler, and still enjoys watching Sesame Street). “I delve into my past experiences and current struggles,” Rijneveld once stated. “For me, it’s about turning something sad or beautiful into art.” Being a careful reader can sometimes feel like an invasion; do we truly want to know the origins of My Heavenly Favourite? Yet I cannot deny that these thoughts contribute to my perception of its unholy brilliance.

Source: theguardian.com