Could cheating, spying, and even murder be happening within the Stasi’s football team?

I

In today’s era of mega-clubs controlled by wealthy individuals such as sheikhs or oligarchs, the East German Oberliga – which functioned in secrecy behind the iron curtain – holds a certain charm. This league had no billionaires investing in teams, agents negotiating deals, or transfer fees to worry about. Football players and coaches were employed by the government, and teams had names that reflected their true nature, such as Lokomotive Leipzig, Turbine Weimar, and Motor Suhl.

The documentary “Stasi FC” sheds light on the fact that true socialism was just as capable as turbo-capitalism of creating oppressive monopolies. The dominant East Berlin team, BFC Dynamo, may have won the German Democratic Republic’s championship 10 times in a row, but they did so through bullying tactics that would make teams like Manchester City or Paris Saint-Germain seem like innocent grassroots initiatives, and the supporters of Millwall FC appear politically correct. The team even used the secret police to monitor their own players and violently punished those who left to play for West German teams – possibly even going as far as to assassinate them.

East German football promoted fairness and unity among all individuals. Athletes were frequently encouraged to act as “diplomats in sportswear” to showcase the successes of the socialist regime. At BFC Dynamo, party officials held weekly training sessions for the team on how to interpret global affairs in the correct manner.

However, if the leader of a club in your league also holds the position of the secret police chief in an authoritarian state, the concept of socialist football is not truly fair.

Ralf Minge, a former striker for Dynamo Dresden’s biggest rival team, recalls that it was well known that Dynamo Berlin was favored by Erich Mielke, the head of the Stasi, and received protection from him. As a result, they were seen as the top rival for every other team, and playing against them meant a strong desire to win.

Mielke, a red-hot communist who built up the largest secret police apparatus in the world per capita, was not only BFC’s biggest fan but the club’s honorary president. When he decided in the 60s that East Berlin needed not just to concentrate political power but hoard trophies, he did not need a lavish transfer budget to make it happen. He simply bent the system to his will.

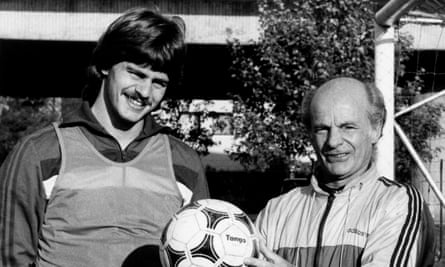

The most successful team in East Berlin, ASK Vorwärts Berlin, was relocated to Frankfurt and Oder, giving control of the city’s young talent to Mielke. Rather than being sought out, promising football players from smaller clubs were ordered to join BFC if Mielke desired them. Falko Götz, who played for Dynamo from 1971 to 1983, recalls, “If Mielke wanted a player, they would be told: ‘you will play for BFC after the summer, and if you refuse, you will no longer be able to compete in sports.’ It didn’t matter what your contract stated.”

Due to the fear of the strict control of the Stasi, referees consistently blew their whistles in favor of Dynamo. In a critical game in 1986, the opposing team’s captain from Lokomotive Leipzig was ejected for a minor offence, and the referee prolonged the match until he could award a penalty to the Mielke club in the 95th minute. Götz admits, “I was ashamed of what was happening on the field at times. No one wanted to win in that manner.”

The club’s followers started to absorb the negative energy from other teams. Ironically, the club that was supposed to exemplify the superiority of socialism became the preferred team for neo-Nazi hooligans in East Berlin. Fans praised Mielke and created their own version of the saying “No one likes us, we don’t care”: “My grandfather was in the SS, my father was in the Stasi, and I support BFC.”

The club’s achievements cannot solely be attributed to intimidation or unfair officiating. Minge acknowledges that BFC Dynamo had a strong team. The youth centers where they recruited players were more advanced than those in the western part of Germany. According to Götz, East Germany received limited international recognition through sports, so they heavily invested in training their young athletes.

Football players who emerged from East German academies were skilled with both feet, had good tactical understanding, and were physically fit. According to Minge, their training was diverse, including gymnastics once a week where everyone could do a handstand on the parallel bars. After the reunification of Germany, some players from West Germany joined and Minge noticed that they lacked basic physical abilities like pull-ups. This was frustrating for Mielke as he watched his favorite team continuously struggle on the global stage. Götz also recalls how some teammates had impressive records in domestic competitions, but faced constant failure in European Cup games due to the team’s overall poor performance.

after newsletter promotion

Minge believes that the militaristic tactics used in sports by East Germany, which allowed them to surpass their larger Western competitors at the Olympic Games, ultimately held them back on the field. He explains, “We lacked a certain mindset. We functioned more like military units, following strict rules imposed from higher authorities. This did not allow for us to fully utilize our own abilities.”

Götz, along with the socialist regime, was disappointed by the lack of success on the international level. According to him, despite winning the championship three times by the age of 20, he lacked perspective. He believed that in West German football, players were solely responsible for their own accomplishments.

However, it would have been a significant blow to the reputation of the Stasi if players from their prestigious project had defected to the west. This was a concern for the secret police, who were well aware of the potential consequences. In 1979, Lutz Eigendorf, a midfielder for BFC and a favorite of Mielke, managed to evade his monitors on a trip to West Germany and seek asylum there.

The State Security Ministry responded with anger: without the knowledge of western intelligence, up to 50 Stasi informants closely monitored Eigendorf’s actions once he started playing in the Bundesliga in West Germany. Stasi FC recounts the events of a secret police operation in 1981 where three Dynamo Dresden players were arrested in order to set an example for other potential defectors. They were imprisoned for 11 months on charges of Republikflucht, or “deserting the republic”.

Unfortunately, two years later, Eigendorf passed away in a car accident. While there is no concrete evidence of the Stasi’s involvement, it instilled fear in many players. Götz states, “I am unable to confirm what truly occurred as there is room for speculation, but I have no doubt that the Stasi was capable of it.” Despite this, in 1983, Götz and his teammate Dirk Schlegel took a risk and hailed a cab during a shopping trip before an away game in Belgrade, ultimately seeking refuge at the West German embassy.

In 1988, BFC Dynamo maintained their winning streak and secured their 10th consecutive championship title. However, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the club faced a collapse as 22 players, including two starting lineups, departed for the west during that same season. After declaring bankruptcy in 2001, the club was able to stabilize its financial situation and currently competes in the fourth tier of German football. The team’s supporters are still known for their aggressive behavior and should be avoided.

Many football players came to realize the consequences of their decision to play for the secret police’s team, known as a Faustian pact, only after the Stasi archives were made public in 1992. One player, Götz, spent four days reading through his file in Berlin and was shocked to discover that some of his close friends had been spying on him and his family. This discovery led to the end of those relationships and a deep realization of the dark depths of humanity.

According to him, there was one noticeable trend. The individuals who secretly observed him were typically those who lacked the skill to sustain a career in professional football solely based on their abilities.

The documentary “Stasi FC” will air on Sunday, November 26 at 9pm on Sky Documentaries.

Source: theguardian.com