Ski resorts are using more environmentally-friendly methods for making snow in order to combat the effects of climate change.

T

As he makes his way across Bromley Mountain Ski Resort on a sunny January afternoon, Matt Folts glances at his smartwatch and grins. The temperature reads 14 degrees Fahrenheit, which happens to be his ideal snowmaking temperature. It’s just cold enough for the water to freeze quickly, but not so frigid that his long shifts on the mountain become unbearable.

Folts serves as the chief snowmaker at Bromley, a petite skiing destination located in the southern portion of Vermont’s Green Mountains. The robust 35-year-old dons a handlebar mustache, an orange safety jacket, and sturdy winter footwear that creates a crunching sound as he moves through the snow. A blue hammer hangs from his belt.

Skiers may be wrapping up their day, but not Folts. He will continue working well into the evening to prepare the mountain for the next day’s visitors. Making his way past Sunder and Corkscrew, he makes his way to a short snow gun that is used to cover Blue Ribbon, a trail reserved for experienced skiers and named after Bromley’s founder, Fred Pabst Jr. The equipment stands a few feet tall and has three legs, with a metal head pointing towards the sky. Two hoses resembling fire hoses supply the machine with water and compressed air, which it uses to produce snow by spraying it into the air. As the water droplets fall, they come together to form snowflakes.

Folts remarks that he would resemble a yeti if the snow was warmer and wetter. However, he is satisfied with the current temperatures as the freshly made powder gently bounced off his sleeve.

However, the production of perfectly fake snow, such as Folts’, presents a dilemma for the climate. On one hand, the process of making snow consumes a significant amount of energy, leading to emissions that contribute to global warming. On the other hand, as the planet continues to warm, artificial snow has become increasingly necessary for the ski industry, which generates over $20 billion in revenue for ski towns across the country. The encouraging news is that resorts have been actively improving the efficiency of their snowmaking processes in response to this growing threat, in hopes of mitigating the impact of rising temperatures.

Last season, ski resorts in America received over 65 million visits. It is estimated that a significant portion of these visits occurred during the Christmas week, which can greatly impact a resort’s annual revenue. The weekends of Martin Luther King Jr and Presidents Day are also crucial for resorts. However, maintaining suitable skiing surfaces has become increasingly unpredictable.

The snow levels in the western United States have decreased by 23% since 1955. Rising temperatures have also caused the snowline in Lake Tahoe, California to move from 1,200 to 1,500 feet. A study revealed that many areas in the northern hemisphere are approaching a critical point where even slight temperature increases could result in a significant decrease in snow.

According to a calculation, approximately 50% of the ski resorts in the Northeast may not be financially sustainable by the middle of the 21st century. Studies show that Vermont’s skiing season could be reduced by two to four weeks by 2080, while another research found that Canada will need to increase its snowmaking capabilities by 67-90% by 2050. At Bromley, snowmaking machines have been crucial for many years; without them, the number of trails open in mid-January would have likely been in the single digits instead of 31.

Creating a terrain for skiing and snowboarding requires a significant amount of resources. Pumping water uphill and pressurizing air to operate snow guns requires a lot of power. Bromley, a relatively small ski resort, produces enough snow to cover 55 hectares (135 acres) with at least three feet of snow each season. However, this results in a high electricity consumption, equivalent to powering about 100 homes. As a result, the resort’s utility bill increases by almost $500,000 annually.

Display the image in full screen mode.

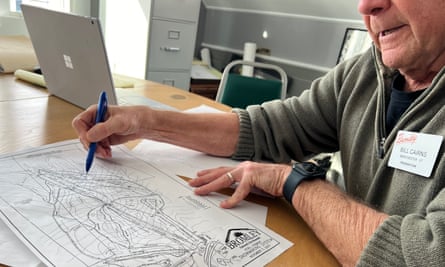

According to Bill Cairns, the president and general manager of Bromley, the system has become significantly more efficient in the past ten years. He used to spend $800,000, but now he can produce more snow for half the cost. This decrease in snowmaking expenses has been a major gamechanger.

Snowfall begins with small particles of dust in the air. As they descend, they gather water droplets and become snowflakes. Ski resorts, such as Bromley, mimic this phenomenon by utilizing extensive networks of pipes that supply water and compressed air to numerous snow machines spread throughout the mountain.

In 1965, Fred Pabst Jr, from the famous beer family, spent $1 million to install a system that combined compressed air and water in a chamber. This system utilized air pressure to shoot water droplets into the sky through a large nozzle, making it one of the earliest systems used in American resorts.

Slavko Stanchak, a renowned snowmaker, recalls that the process was once an enigma to them. During a time when energy was inexpensive, ski resorts would lease fleets of diesel compressors to produce snow on the slopes. However, as energy expenses increased in the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a greater drive to find inventive solutions.

Stanchak explains that our main goal was to ensure the process was financially feasible.

He established a consulting firm that aided ski resorts, such as Bromley, in enhancing their snowmaking processes. In terms of water management, Bromley made considerable improvements to their piping system in the 1990s and also implemented a mid-mountain pump to transport water from their ponds to the trails. However, a large portion of the water is eventually returned to the natural watershed during the spring thaw. As the necessary water amount for snow coverage on a ski slope remains consistent each year, there is a limit to the efficiency improvements that can be made. The main cost factor is the compression of air.

According to Cairns, the sky is where the small dollar bills can escape. He also mentions that two diesel compressors have the ability to use up an entire tanker truck’s worth of fuel in just one week.

In the 1990s, there were advancements in snow guns that made them more efficient. Some people found that using devices with many small holes instead of one large hole could use water instead of air pressure to push fluid upward. This allowed them to place the air nozzles on the outside of the gun, which mainly broke the water into droplets. This was a less demanding task than pushing the water out of the gun.

“A traditional hog may require 800 cubic feet per minute of compressed air, whereas this one only uses about 70,” Folts explains, gesturing towards a tower gun from the early 2000s that is approximately 15 feet tall and cannot be easily relocated like the ground guns on Blue Ribbon. On the hill, there is a newer model that can function with as little as 40 cubic feet per minute, and further down the slope is the resort’s latest tool, which has the potential to use just 10 CFM in optimal conditions. This marks a significant improvement in efficiency by approximately 100 times.

Efficiency Vermont, a program supported by the state, encourages ski resorts to replace as many of their older, less efficient devices with more efficient ones. According to Chuck Clerici, a senior account manager at the organization, their efforts were significantly aided by the “Great Snow Gun Roundup” in 2014. Prior to this event, they had only been able to make sporadic replacements. However, the roundup resulted in 10,000 old and inefficient models being retired statewide. As a result, Clerici notes that snowmaking operations now use approximately 80% less air than before.

Efficiency Vermont has not distinguished between the savings generated by upgrades in snowmaking and those related to building enhancements. However, it has reported that its initiatives to reduce energy consumption in ski resorts have resulted in over 1 billion kilowatt hours of electricity saved between 2000 and 2022. This is equivalent to preventing nearly a million tons of carbon dioxide emissions, or the same impact as shutting down two gas-fired power plants for a year.

Display the image in full screen mode.

According to Clerici, the largest projects we have undertaken in the past have focused on snowmaking. In terms of energy efficiency, there are few opportunities to replace something that uses only one-fifth of the energy.

Cairns stands beside the building that stores Bromley’s air compressors and gestures towards a concrete slab with two maintenance holes. He explains that these holes used to supply fuel to massive underground diesel tanks. On his right, there is a marked pipe where the polluting generators used to link to the snowmaking system, but it has now been disconnected.

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Bromley, along with many other snowmaking companies, has successfully reduced their reliance on diesel air compressors through electrification. This switch has also enabled some resorts to utilize renewable energy sources. For example, Bolton Valley in Vermont has a 121-foot-tall wind turbine and many others have incorporated solar panels, including Bromley which leases a portion of land near its parking lot for a solar farm. This solar array generates over half of the energy needed for Bromley’s snowmaking system.

The snowmaking business in America has traditionally been concentrated on the East Coast, where finding natural snow can be difficult. However, there has been a shift towards Western states. According to Ken Mack, an employee at HDK Snowmakers, one of the leading equipment manufacturers, they are now focusing more on the West. In fact, one of the company’s executives has relocated to Colorado in order to meet the growing demand in that region.

According to Mack, HDK’s current snow guns may have reached their maximum efficiency in terms of water and compressed air usage. This has led to the need for finding improvements in other areas.

According to Mack, snowmakers can improve their practices by monitoring their energy consumption, preferably in real time. He is currently working on promoting the use of a metric called the Snowmaking Efficiency Index (SEI), which calculates the number of kilowatt hours needed to produce 1,000 gallons of snow on the slopes. This measurement was initially introduced by Stanchek but never gained widespread use. (As a point of reference, it takes approximately 160,000 gallons of water to cover one acre with 1 foot of snow under optimal conditions.)

If this information is made available to the public, it could promote transparency and allow ski resorts to showcase their productivity. This is especially attractive as sustainability and environmental responsibility are becoming more important to consumers. However, since SEI differs greatly between different mountains and depending on temperature, it may be most useful for resorts to use as a means of self-improvement rather than as a means of comparison against other resorts.

This season, Bromley’s SEI varied from approximately 23 during the initial warm weeks to the mid-teens as temperatures decreased. Cairns makes an effort to surpass these figures and is able to track them from his workplace. If the number suddenly increases, he can investigate for potential issues such as an unsecured gun, a damaged water line, or any other possible causes.

According to Cairns, any number less than 20 is deemed highly desirable, indicating a positive trend in our progress.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

A more revolutionary development in snowmaking is the move toward automated systems that can be operated almost entirely remotely. One obvious benefit is reducing the need to find people willing to schlep around a mountain in the dead of night, when temperatures can dip into single digits. More importantly, automation allows resorts to ramp snowmaking up and down quickly, which is particularly useful as global temperatures climb.

Snow can be made when the temperature reaches approximately 28 degrees Fahrenheit (although it is most effective at 22 degrees or lower), which is only occasionally reached for short periods by Mother Nature. In such cases, resorts can easily take advantage by simply pressing a button instead of sending a team to manually turn on all the snow guns. This also results in less energy consumption for operating pumps and compressors, making it more efficient for transporting people up and down the mountain.

Mack states that using automation can help complete a task faster. For example, a trail that usually takes 100 hours to cover could be reduced to just 20 or 30 hours. This results in significant time savings. Additionally, it provides some flexibility in case extra time is needed.

Europe has a significant lead over North America in terms of automation, largely due to government subsidies for the high costs of installing electricity and communication infrastructure in mountainous areas. These subsidies have allowed smaller ski areas in warmer regions, like the mid-Atlantic, to benefit from automation and survive. However, larger resorts in colder regions, such as Stowe, Stratton, and Sugarbush in Vermont and Big Sky in Montana, have also begun experimenting with automation technology.

Cairns believes that automation will play a significant role in the future of snowmaking. However, due to the high cost involved, there is currently no one willing to financially support it.

Bromley is currently experimenting with a partially automated gun that has the ability to prevent wiring problems. This gun utilizes the current compressed air supply to rotate an internal turbine, generating sufficient energy to power a compact onboard computer. Through monitoring weather conditions, it can autonomously regulate the amount of water and air flow to achieve the best snow production.

Folts stated that the guns do not require any power as he completed adjusting one gun and proceeded to the next. He described it as being on a higher level.

Until that time, Folts and his team continue to move slowly through the night, handling one gun at a time.

-

This article was jointly published with Grist, a non-profit news outlet that focuses on climate, social justice, and ways to address these issues.

Source: theguardian.com