Did the true events behind Free Willy alter the narrative for captive orcas, as you previously misled us?

A

Those who were raised in the 1990s likely have a vivid memory of a scene from a movie where a 3.6-ton orca jumps over a harbor wall and swims away into the sunset with its family. This was the ending of Free Willy, a film that deeply resonated with many, as it follows a young orphan’s race against the clock to release a killer whale from captivity before it is killed.

Rewording: This month marks the 30th anniversary of the film’s release in the UK, which led to three sequels and a TV series. However, it also shed light on the negative effects of keeping orcas in captivity, particularly through the real-life story of Keiko, the orca who played Willy. It took many years and a significant amount of money to rescue him, but the outcome was not a Hollywood-worthy ending.

Once the movie became popular, audience members discovered that the actual Willy was not living freely. He was instead confined to a marine theme park in Mexico City, enduring unfavorable circumstances. According to Rob Lott, a campaign coordinator for Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC), a captive orca would need to swim over 1,000 loops in its enclosure in order to cover the same distance it would swim in the wild.

According to Charles Vinick, director of the Whale Sanctuary Project (WSP), numerous children contacted Warner Bros film studio and the marine entertainment park, expressing their disappointment and accusing them of deception.

David Phillips, an environmentalist and former director of the Earth Island Institute, was requested to travel to Mexico City in order to assist Keiko. Upon arrival, he noted that the orca’s dorsal fin was bent, he had a papillomavirus on his skin, and he appeared to be severely underweight.

K

In 1979, when eiko was around two years old, he was caught near Iceland and separated from his family. He later became famous for his role in Free Willy. However, releasing him back into the wild would be a difficult and expensive task.

Phillips, founder of the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation (FWKF), believes that despite the slim likelihood of finding Keiko’s family, there is still a possibility as female orcas have a lifespan of up to 90 years. This gives hope that his mother may still be alive.

Display the image in full screen mode.

In 1996, Keiko was transferred to a custom-made tank at the Oregon Coast Aquarium, where he was no longer required to perform and had access to a larger area, fresh fish, and cold seawater. After two years of rehabilitation, his relocation back to Iceland was approved by veterinarians, the US Congress, and the Icelandic government.

In September 1998, he was transported from Oregon to Iceland via a US air force C-17 military transport jet. The flight required two refueling stops and Vinick, who accompanied Phillips and Keiko, still has a framed photo of the C-17 in his office.

Keiko was inside an open-topped shipping container on the plane, surrounded by ice water up to his fins. The staff had to continuously add ice as his body heat raised the temperature, but Keiko remained peaceful and composed during the trip. According to Phillips, it’s possible that he had an intuition that he was returning to his natural habitat.

When the whale arrived at the custom-made pen in Klettsvik Bay, Iceland, it was not the conclusion of its voyage. According to Vinick, the term “release” gives the impression that the gate is opened and the whale simply swims away, never to be seen again. However, this is not an accurate representation for orcas and other cetaceans.

Keiko had forgotten how to survive and was unaware that live fish could be eaten. When prompted to catch one, he would bring it back to his trainers, as if playing fetch, he explains.

Over time, Keiko became skilled at accompanying a boat for extended distances in the vast ocean. In order to keep pace with untamed orcas who swim 100 miles daily, he had to develop his endurance and ability to hold his breath, just like how an individual would prepare for a marathon, according to Vinick.

In 2002, the team lost track of Keiko when their boats were forced to seek shelter due to a severe storm. Over the next few weeks, he traveled hundreds of miles from Iceland to Norway and arrived in remarkably good health, indicating that he had been able to find food for himself.

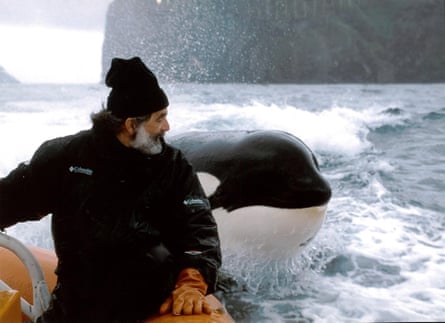

Keiko’s affection for humans, especially children, continuously pulled him towards social interaction. While in Norway, he encountered a father and daughter fishing and followed them to the shore. He spent the remainder of his life traveling between different Norwegian fjords.

U

Unlike Willy, Keiko was never able to be reunited with his family. In December 2003, Vinick received a phone call informing him that Keiko had passed away from pneumonia at the age of 27. Vinick, who was deeply affected by the news, explains that orcas have a unique ability to hide signs of illness until it becomes critical. Unfortunately, Keiko’s abnormal breathing was not noticed until it was too late.

Display the image in full screen.

Some people criticize Keiko’s return to the ocean because he was not able to fully adjust to life in the wild. However, Phillips does not believe that should be the only measure of success.

He feels a sense of accomplishment that Keiko was able to leave Mexico City, where he believes he would have died, and return to his natural habitat. Keiko was able to learn how to hunt for food and ultimately make his way to Norway. The International Marine Mammal Project points out that eight captive orcas passed away while Keiko was under the care of the FWKF at SeaWorld.

His impact goes beyond just altering views on captivity; it also serves as proof that coastal sanctuaries can be successful. Keiko was the initial orca in captivity to be released back into the wild, demonstrating that these creatures can thrive in conditions that closely resemble their natural habitat. Klettsvik Bay, where he resided in his seaside enclosure, is currently home to the Sea Life Trust’s beluga whale sanctuary.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Similar to Keiko, the majority of captive whales and dolphins would struggle to survive in their natural habitat as they have been raised in captivity. However, experts advocate against keeping these animals confined in cramped and artificial tanks that hinder their ability to use echolocation, a crucial skill for navigation, finding food, and hunting.

Similar to sanctuaries for elephants or big cats rescued from inadequate environments, a whale sanctuary by the seaside offers a natural setting and prioritizes the well-being of the animals above all else. This allows them to have more room to roam, deeper waters to swim in, and a sandy ocean floor to interact with other marine life like birds, fish, and crabs. While visitors can observe the whales from a distance, they are not expected to perform.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Vinick, from The Whale Sanctuary Project, states that they are establishing a coastside sanctuary in Canada and advocating for the creation of similar sanctuaries globally. These sanctuaries will provide former captive cetaceans the opportunity to live the rest of their lives in their natural ocean habitat. Vinick emphasizes the importance of making amends for the distress inflicted upon these animals.

B

The state of captivity persists. Based on the WDC’s report, there are currently 3,600 whales and dolphins being held captive in 58 different countries, with at least 56 of them being orcas. The WDC advocates for an end to breeding, transfers between parks, and performances, and for better welfare standards to be implemented.

New laws have been implemented in Canada, France, the US, and South Korea to strengthen legislation. Russia, which used to be the only country that captured orcas and belugas for captivity, has also stopped this practice and their whale jail has been taken down.

The attention has shifted to China, where it is believed that they currently hold one third of all captive whales and dolphins, according to Lott. The WDC’s latest data shows that China has a breeding program for orcas, with 99 facilities housing marine mammals and 10 more in the process of being built.

In the past, there were over 30 establishments in the United Kingdom that held whales or dolphins. “It’s hard to imagine that they had orcas as part of a pier show in Clacton,” remarks Lott.

Even though there have been no cetacean facilities in the UK for 30 years, keeping them in captivity is not against the law. However, activists are pushing for a ban to ensure that it never happens again.

Harry Eckman, the CEO of the World Cetacean Alliance, is frustrated that there are still numerous locations keeping these intelligent creatures in captivity. “I can’t comprehend why we’re still discussing this,” he stated.

Most captive orcas are underweight, with compromised immune systems and teeth worn down to nubs from gnawing on their tank bars. They will never be able to fend for themselves, Vinick says, “but we owe them a better life.”

Vinick stated that Keiko is the sole orca to have been successfully released back into its natural habitat. He also mentioned that while it is relatively simple to capture a whale, it is a difficult process to return one to the wild.

Source: theguardian.com