. The plane I was on crashed in the Andes mountains. It was unimaginable, but it was the only thing that kept me and the other survivors alive while we were starving.

A

All that Nando Parrado can recall is a dark void and a constant belief: “I am deceased. This is the end. It’s so dark that this must be death.” Time went by, possibly days. Then, a new realization: “I am parched. I yearn for water. If I am truly dead, I would not feel this thirst.”

He became more alert. What caused the chilly sensation? Why was his head pounding? Suddenly, he heard voices. Parrado opened his eyes.

“I can vividly recall the lovely, unblemished faces of my friends,” he reminisces. “They kept repeating, ‘Nando, are you alright? Nando, are you alright?’ But I was not. The plane had crashed.” As he surveyed his surroundings, he realized he was trapped inside a twisted wreckage that had flipped onto its side. The destruction was severe: pipes and wires exposed, metal crushed, plastic shattered, debris scattered everywhere.

Unable to reword.

“I received the devastating news that my mother and best friend Francisco “Panchito” Abal had passed away,” Nando recalled. During the flight, Panchito had convinced Parrado to give up his window seat for him. “Panchito was like a brother to me, spending a few days each week at my house and even borrowing my clothes.” Nando also noticed Susy, who was severely wounded, lying on the floor near the cockpit.

I made my way to my sister’s side and hugged her as we both sat on the ground. She was immobile and unable to speak, only able to move her eyes. Her shoes were missing from the accident and her feet had turned purple. Those are the lasting memories I have. I stayed with her, using my mouth to melt snow for water since we had no cups.

Parrado stayed by her side until the following morning, when he stumbled out. The remaining parts of the plane had come to a halt on a glacier. The only view from the east was of snowy mountain peaks and steep valleys. They were surrounded by mountains in every other direction. “I realized the vastness of our location. It’s massive. It’s enormous,” he recalls. “And I thought to myself: ‘Oh no. This is going to be terrible. How will we ever escape from here? They won’t be able to locate us.'”

P

Parrado’s prediction was correct – a rescue team was not able to locate them. However, 72 days after the Uruguayan air force flight 571 crashed into a ridge and landed deep in the Andes, Parrado and 15 other passengers managed to escape the mountain and survive. This remarkable story of endurance was dubbed “The Miracle of the Andes” by newspapers at the time. Speaking from his home in Montevideo, Uruguay via videocall at 73 years old, Parrado does not see it as a miracle. Rather, he believes it was the determination and trust among a group of young individuals that ultimately led to their survival.

Parrado is a practical person. Even after 50 years, he remembers the events with a precise and objective attitude. For 26 years, he kept silent about his experiences, but was eventually persuaded to share his story and has since traveled extensively to do so. He claims he is not a motivational speaker, but I personally disagree. His warm demeanor, powerful voice, and poetic way of speaking leave you feeling energized as he talks about his time in the Andes, his admiration for his father Seler, and his enthusiasm for life.

Parrado is not known for doing many interviews, but he felt compelled to share his thoughts leading up to the release of Netflix’s thriller, Society of the Snow. This is the second major film to depict the story of the survivors, following Alive in 1993. Parrado has watched the new film twice and praises it as an exceptional piece of cinema. It is highly likely to be nominated for best international feature film at the Academy Awards. Parrado conveyed to the director that after people see the film, they will truly comprehend the challenges they faced. He believes that the director has accurately captured the essence of their experience. Even Parrado’s wife was moved by the film and expressed a newfound understanding of their struggles.

I

In October 1972, at the age of 22, Parrado was an average middle-class man from Uruguay, eagerly awaiting to begin university. He worked at his father’s hardware store, rode his motorcycle, pursued romantic interests, and played rugby for his school’s alumni team, Old Christians. He had been friends with most of his teammates for over ten years and had previously gone on a trip to Chile with them for a game. When a second trip was planned, he was determined not to miss it.

Marcelo Perez, the leader of their group, had arranged for a plane to transport them to Santiago, Chile. Parrado’s father dropped him off at the Montevideo airport, accompanied by his mother and younger sister (his older sister, Graciela, remained at home). Due to unfavorable weather conditions, the flight made an unexpected stop in Mendoza, Argentina, where the team spent the night. The pilots faced delays the following day (which were met with criticism from some of the rugby team members), but the plane was on lease from the Uruguayan air force and regulations prohibited it from being on Argentinian land for more than 24 hours. They boarded the plane at 2pm and departed shortly after. This was considered the most challenging time of day to fly over the Andes, as the warm afternoon air created unstable atmospheric conditions.

When reflecting on the flight, Parrado realizes how naive he was. He admits, “Nowadays, I would never even consider boarding that airplane.” The Fairchild FH-227D had weak engines and was carrying a full load of passengers while flying over the treacherous South American mountains in unfavorable weather conditions. In hindsight, Parrado believes it was a reckless decision.

The flight departed from Mendoza on Friday, October 13th, a detail that did not go unnoticed by the rugby team, who made light of the date’s superstitious connotations. A total of 45 individuals were on the plane – the team, their loved ones, and the crew – along with an unknown passenger who had purchased a ticket in order to attend a wedding. Unfortunately, flying directly over the Andes was not feasible due to the plane’s maximum altitude of 6,858 meters (22,500 feet), as the highest peak in the range, Aconcagua, stands at 6,960 meters. Instead, the flight would take a U-shaped path: first heading 100 miles south, then crossing over the Andes through Planchon Pass where the ridges are lower, before finally turning north towards Santiago. The entire flight was expected to take approximately 90 minutes.

Approximately an hour after takeoff, the inexperienced co-pilot made a mistake in judging his position, possibly because of obscured visibility or incorrect calculations of wind. He turned the plane in a northern direction too soon, leading it further into the Andes. Unaware of his mistake, he started the descent for landing.

The Fairchild encountered dense fog. The steward instructed the passengers to buckle their seatbelts. The plane experienced severe turbulence and suddenly dropped a significant distance due to hitting an air pocket. Panchito nudged Parrado and gestured towards the dangerously close mountain outside the wing. Parrado recalls only bits and pieces: the realization that they were too close, some shouts, and the concerned expressions of his mother and sister. Then, the plane began to ascend rapidly with its engine roaring and fuselage violently shaking. “I heard a noise, similar to an explosion,” Parrado recalls, “like a Formula One car colliding head-on with a wall.” The sky cleared above him as he was thrown forward in his seat. And then, “I felt like I was dying without even realizing it. I entered into a dark void, I don’t know what…like a piece of the universe?”

Parrado’s companions eventually informed him of what had happened. The pilots had attempted to raise the plane above a mountain that was approaching, but the underside collided with the ridge. The wings separated from the aircraft. The left propeller of the plane sliced through the body of the plane. The tail broke off around where Parrado was seated. The body of the plane slid down the mountain at a frightening rate. Once it came to a halt, the seats in the cabin were thrown forward, tearing from their fastenings and collapsing on top of each other, causing harm to several passengers.

Upon encountering the wreckage, those who were able quickly took action to aid the injured and trapped individuals. Team captain Perez assumed control and led the efforts. Medical students Gustavo Zerbino and Canessa worked with what resources they had, using clothing strips to bandage broken bones and cooling them with snow. The pilot, who was found trapped in the damaged cockpit, informed them that they had reached the western limits of the Andes, near Curicó, before passing away. In order to protect themselves from the harsh winds, they constructed a makeshift wall using suitcases, seats, and plane fragments in the fuselage. Any openings were covered with snow. Out of the 45 passengers on board, 33 survived, with 32 huddling together for warmth on the first night.

Initially, Parrado was thought to have died, but it turned out to be fortunate. He recalls, “They abandoned me in the snow without water or hydration.” Neuroscientists later explained that the combination of cold temperatures and lack of fluids prevented his head injury from swelling and causing his death. Eventually, one of his friends noticed signs of life in Parrado and decided to bring him closer to the fuselage where the rest of the group was located.

Parrado continuously felt on the brink of death from the moment he woke up. The group was at an altitude of over 3,350 meters in the freezing Andes, with temperatures reaching -35C. The constant blizzards and thin air made it difficult to even stand still without losing breath. The blinding sun and endless white environment caused painful blisters. A single misstep could result in being buried in snow. They lacked any proper gear such as coats, blankets, or mountaineering equipment.

Parrado was most shocked by the intense thirst he experienced. He realized that staying hydrated was crucial at high altitudes, as dehydration occurs five times faster there compared to sea level. However, finding water was a challenge, so they resorted to eating snow. The cold temperatures were so harsh that it caused discomfort and damage to their throats and lips.

The evenings were harsh. The improvised barrier never provided complete shelter from the gusts of wind; the fabric pieces they had torn from the chairs provided minimal relief from the freezing temperatures. Their garments became icicles. They struck each other’s arms to promote blood flow. They trembled and their teeth chattered so intensely that conversation was out of the question. They clustered together and sought warmth in each other’s exhalations. “It’s amazing how reduced you become when you seek that warmth,” Parrado reflects. At times, all he could do was count down the seconds until daybreak. They would wake up with frost in their hair.

Their hope diminished. They spotted a plane on the fourth day, but it was unable to see the white wreckage from such a high altitude. Three boys attempted to climb the mountain on the fifth morning, using makeshift snowshoes made from cushions and seatbelts tied to their feet. However, the challenge proved to be too difficult and they returned in the afternoon. On the eighth day, Susy passed away in Parrado’s arms. He felt very little in that moment. He later realized that his brain only focused on survival and he couldn’t express any emotions or cry. The next morning, he buried her.

The threat of starvation was looming. In desperation, some of the survivors resorted to consuming scraps of leather from damaged luggage. Their supplies were meager, consisting of chocolate, nuts, sweets, crackers, fruit, jars of jam, three bottles of wine, and some liquor. Each meal was limited to a small square of chocolate or a similar portion. Parrado even took three days to finish one chocolate-covered peanut. After a week, he made the difficult decision to consume the flesh of their deceased comrades. He confided in his friend Carlitos and expressed his willingness to do so.

“I had no uncertainties. I had reached a clear conclusion in my mind. Absolutely certain. This is the sole solution,” he states. “The fear of not knowing when one will have their next meal is the most intense fear for a human being. The most instinctual fear.”

Once the discussion was extended to the entire group, the argument continued throughout the afternoon. While a few members were reluctant, most sided with Parrado. A small number of individuals left the airplane wreckage to find glass to use for cutting meat. Some even made a vow to offer their bodies to the others in the case of death. Roy Harley, one of the boys, was able to get a transistor radio functioning and on the eleventh day, they heard a broadcast announcing the halt of the rescue attempt. This news prompted everyone to start consuming food. “In that situation, anyone would have come to the same conclusion. And it’s not as difficult as you may think.”

Parrado was eager to depart once he realized the rescue team would not be arriving, but his injuries were too serious and the weather was harsh. As time passed, they became familiar with the necessary techniques for survival, such as avoiding hazardous crevices and warming snow in bottles for drinking. “We adapted to our surroundings. We began to acquire knowledge. I even learned how to navigate through snow. After a month in the wilderness, we were like seasoned mountaineers, equipped with the necessary skills.”

Unknown to them, the aircraft was positioned at the bottom of a narrow valley on the mountain, known as a couloir, where snow accumulates. A little over two weeks later, an avalanche occurred, burying everyone who was asleep on the floor of the plane. Roy Harley, who had stood up upon hearing the loud noise of the avalanche, likely saved their lives by doing so. He quickly uncovered three others and then they started searching for more people, clearing snow from their faces to help them breathe. They continued to dig for the next person.

“I was unable to move and found myself buried under debris, but I was still able to breathe.” For half an hour, Parrado remained in this state. Out of the 27 individuals who were still in the plane’s fuselage that night, eight did not survive. The remaining survivors were stuck in a fuselage that was partially filled with snow and completely dark. They were unable to stand due to their injuries. Meanwhile, a blizzard raged outside. After a few hours, Parrado used a cargo pole to create a hole in the roof of the plane, allowing fresh air to enter. They remained in this position for four days, surrounded by the bodies of those who had perished.

“We were uncertain about the amount of air we had. The depth of the snow above us was also unknown – it could have been two, four, or 50 metres,” recalls Parrado. Despite hearing a second avalanche, it did not reach them as they were already buried by the first one. Parrado reflects on the four days they spent trapped under the snow, stating that even hell would have been preferable in comparison. Once the blizzard ceased and they could safely exit, they took turns digging through the cockpit for hours until they reached the surface.

Following the avalanche, Parrado realized that the only means of descent from the mountain was by foot. He spent the next few weeks preparing, waiting for better weather, and creating essential equipment such as a makeshift sleeping bag made from sewn-together cushions and a sled fashioned from a suitcase. When he ran out of notches on his belt, Parrado understood that time was running out. He reflects that his choice to leave was the most crucial decision he has ever made. “I was aware that once I took that first step away from the fuselage, I would not be returning. It was a kamikaze mission.”

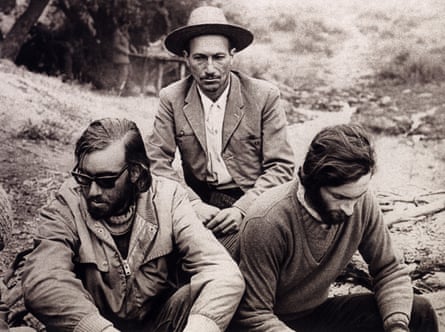

Parrado, Roberto Canessa, and their friend Antonio “Tintin” Vizintín departed from the fuselage on the 61st day. According to the dying message from the pilot, they were under the impression that they only needed to climb the mountain to the west and then make their way to Chile. Parrado was equipped with three pairs of jeans, three sweaters, four pairs of socks inside a shopping bag, rugby boots, an aluminum pole for walking support, and a backpack containing three days’ worth of meat rations. Before leaving, he reassured those who stayed behind that they could use his family as a source of food if necessary.

According to experts, it is not advisable to ascend more than 300 meters per day in high mountains. However, the group managed to climb twice that amount in just one morning. As a result, they experienced altitude sickness, with Parrado’s heart rate rising and coming close to hyperventilation and dehydration. Their initial estimate was that the climb would take 14 hours, but it ended up taking three days. On the first night, the temperature dropped significantly, causing their water bottle to break.

Parrado was the initial person to successfully reach the top of the summit. They began their ascent at an altitude of 3,570 meters, with the peak standing at 4,600 meters. However, any sense of happiness he may have had upon reaching the summit quickly disappeared as he surveyed his surroundings. Parrado soon came to the realization that the pilot had made a mistake. Instead of seeing the lush green valleys of Chile, all he could see were distant ridges and peaks on the horizon.

“We believed we were only five kilometers from our destination, but in reality, we were 80 kilometers away.” In that moment, he made one of the most important decisions of his life: to keep moving west. “I urged Roberto, ‘We can’t turn back now. What’s the point? I’d rather face death looking into your eyes. Who knows who will die first?'”

Was he prepared for the possibility of death during the trek? “I believe that even if I were to die, or crash, or experience pain or suffering, it wouldn’t matter. You are already dead. So as long as you are still breathing, that’s a bonus. But once you pass through the invisible gates of death, nothing else matters.” Before starting their descent, Parrado named the mountain after his father by writing “Mt Seler” with lipstick on a bag and placing it under a rock. They took Tintin’s rations for their journey and sent him back to the fuselage (he returned in just one hour, using a sled). Parrado and Roberto then began their descent.

Each day, they faced challenges as they descended. The unforgiving terrain gradually became gentler. Along the way, they came across a river and decided to follow its course. Encouraged by signs of civilization such as campsites, animal waste, and livestock, they pressed on. Eventually, they encountered three individuals on the opposite bank of the river. Despite the loud rush of water, they managed to communicate through written messages attached to a rock. The men tossed some bread to the struggling group before riding off to seek assistance from the nearest police station, which was a 10-hour journey by mule.

Parrado and Canessa had trekked over 37 miles in a span of 10 days. Parrado is of the opinion that they could have endured for one more day. According to Parrado, Roberto was extremely frail and gave his all. Everyone on the expedition gave their utmost, with Roberto being the best partner, companion, and friend he could have asked for.

After many years, when speaking with experienced mountaineers, he learned that his success was due to his lack of knowledge. They explained, “If you had been aware of the challenges ahead, you would never have taken the leap. Your ignorance is what allowed you to succeed.”

When the rescue team arrived by helicopter, they gave Parrado maps. He followed the route they had taken. However, they told him that his friends were not in Argentina as he had believed, but rather 60 or 80km away from their current location. Despite this, Parrado insisted that his friends were there and offered to guide the rescuers. He then noticed Canessa, who was being cared for by a nurse on the floor, and the helicopter being stripped of excess weight. Feeling the rush of adrenaline, Parrado was placed behind the pilot with headphones and a seatbelt, and he suddenly realized the gravity of the situation.

Parrado eventually identified the valley, mountains, and fuselage. The boys appeared as the helicopter continued to circle.

The helicopter touched down and Parrado unlatched the door. “Three of my companions leapt towards me with joy, embracing me and cheering. It was a surreal and overwhelming moment, their first glimmer of renewed life.” Due to limited space, a few of them spent an extra night with the rescue team.

Thirty minutes later, the helicopter touched down at a hospital located in San Fernando, Chile. The medical team quickly approached Parrado with a stretcher. “The distance from the helicopter to the hospital entrance was approximately 50 meters,” Parrado recalled. “But I refused to be carried on a stretcher. I had just crossed the entire Andes on foot and I was determined to finish my journey the same way.”

P

Arrado never wavered in his determination. He came to terms with the possibility of death and at times, it seemed inevitable. However, he never gave up his journey. In a rare display of emotion, he reflects, “The lighthouse was my father.” He understood that his father believed they were all dead. Only someone who has lost their entire family in an instant can truly comprehend the pain he was enduring. Parrado later wrote about his experiences in “Miracle in the Andes,” published as a special gift to his father on his 90th birthday. He acknowledges, “Everything he taught me in my youth ultimately saved my life.”

Parrado was reunited with his father and older sister, Graciela, at the hospital after being rescued. Despite his weakened state, Parrado was able to lift his father, although he had lost 45kg from his original weight of 100kg. At the hospital, nurses helped him remove his clothes for the first time in 72 days. When he looked at himself in the mirror, he was shocked by his appearance. There was no sign of muscle and he could see only bones in his legs and knees.

Following his release, he relocated to a hotel in Santiago with the majority of his fellow teammates who had also survived the tragic event. While they were able to experience a sense of celebration, Parrado felt differently. He reflects, “For me, it was a different experience. Perhaps my struggle truly began when I returned home.” He recalls his father sleeping in his bedroom and often on the floor, holding onto his dog. On the mantelpiece, there was a picture of Parrado with his mother and sister Susy. He says, “All my old friends went back to their homes and were welcomed by their families, girlfriends, and the ordeal was over…”

Their sudden rise to fame was fueled by their personal experiences. “We couldn’t escape the attention of reporters for half a year.” His thin appearance made him easily identifiable. He was constantly hounded by paparazzi and strangers would often approach him on the street to greet him. Some even expressed jealousy towards his situation.

The Catholic church representatives stated that the survivors were not at fault for consuming the deceased, but the media could not resist exaggerating the situation. There were even speculations that the boys fabricated the avalanche. “There are many ethical and religious aspects to this story that can be discussed,” he remarked, “but it never bothered me personally.” He takes pride in the fact that the survivors’ organization, Fundación Viven, helped greatly in promoting organ donation among the people of Uruguay.

“We donated our bodies,” he says. “You could die, and you could help the other ones to live. That was a fantastic thing that we did together. I try to explain to people what happened, and that they would have done the same thing. I don’t try to justify anything.”

Parrado spent nearly a year recuperating physically. He resumed his regular eating habits and gradually resumed his rugby training; 10 months later, he participated in a few matches towards the end of the season. He is hesitant to disclose how long it took for him to recover mentally. How could he accurately determine that? However, he claims he did not experience any emotional distress, did not feel guilty, and did not seek professional counseling.

“I mean, we survived something that is not survivable. We’re going to teach the psychiatrist things that he doesn’t know.”

He does not consider his impressive accomplishment to be the most significant aspect of his life. He values his life after that more. He is married to Veronique and has two daughters and four grandchildren. He is approaching retirement (although he is still working, he is preparing to slow down), marking the end of a career that has included running a thriving television production company, expanding the family hardware business, and even racing cars at one point.

Does he often reminisce about his traumatic experience in the Andes?

He stated that he doesn’t dwell on it too much. However, he did mention that he has never had a nightmare about the Andes in his 51 years of life. He does consider his experience in the Andes when making business decisions, saying that compared to the challenges he faced up there, any decision he makes now seems insignificant. He realizes that during his time in the Andes, every decision had life-or-death consequences.

Did the encounter alter his perspective on death in any way?

At a young age, he explains, one becomes accustomed to death. He has personally witnessed his friends passing away and facing death without fear. Instead, they faced it with courage. However, he clarifies that he values life greatly. Every breath he takes feels like a miracle, as he believes he should not have survived. It is a wonder that he is able to speak to you now.

E

Each year, on December 22nd, Parrado and his fellow survivors gather to remember the day they were rescued. He sees this date as a shared birthday, the year they were given a new life. He has never missed this annual gathering. Last year, they marked the 50th anniversary with their loved ones. They took a photo of 147 people who are still alive because of their rescue. It is a story of survival and they also honor the memory of those who did not make it back.

Not long after the boys were saved, the Uruguayan and Chilean air forces constructed a burial site at the location – a basic steel cross surrounded by rocks. Parrado’s mother, sister, and all those who perished are laid to rest there. Parrado has returned to the site 12 times (“You probably think I’m odd or insane!”). The journey is not a simple one: two and a half days on horseback followed by a 43-mile trek on unpaved roads. Once there, with the comfort of satellite phones, guides, and food, he is amazed by its breathtaking size and splendor.

The individual is not emotional and would not have visited if it weren’t for their father. His father had visited 18 times before his passing to leave flowers on the graves of his wife, daughter, and friends. On their initial visit, the father brought Susy’s beloved teddy bear that she slept with every night. When asked why he does this every year, the father responded, “People go to cemeteries to honor their loved ones – mine is just very far away.”

In 2008, at the age of 92, Parrado’s father passed away. Before his death, he wrote a note requesting that Parrado bring his ashes to the location of the crash. A close family friend fulfilled this request, laying him to rest alongside his wife and daughter near Mount Seler.

My father once mentioned that the Pharaohs, gladiators, and Roman emperors were known for having grand monuments as their tombs. In comparison, we have the vast expanse of the Andes mountains.

In 2006, Parrado revisited the location with his family, including his wife and daughters. They expressed their desire to see the place of their birth and creation. At the site, Parrado’s friend captured a photo of them gazing towards the mountain he had conquered. This photo is the only keepsake Parrado holds from his experience in the Andes. He reflects, “Even though our backs are facing the camera, it represents the four of us and symbolizes my journey. When I embarked on that climb, I didn’t have my family, but now I do.”

Source: theguardian.com