Researchers cultivate miniature versions of organs using cells expelled from fetuses during pregnancy.

Scientists have successfully cultivated small organs from cells shed by fetuses in the womb, providing a significant advancement in understanding human development during late pregnancy.

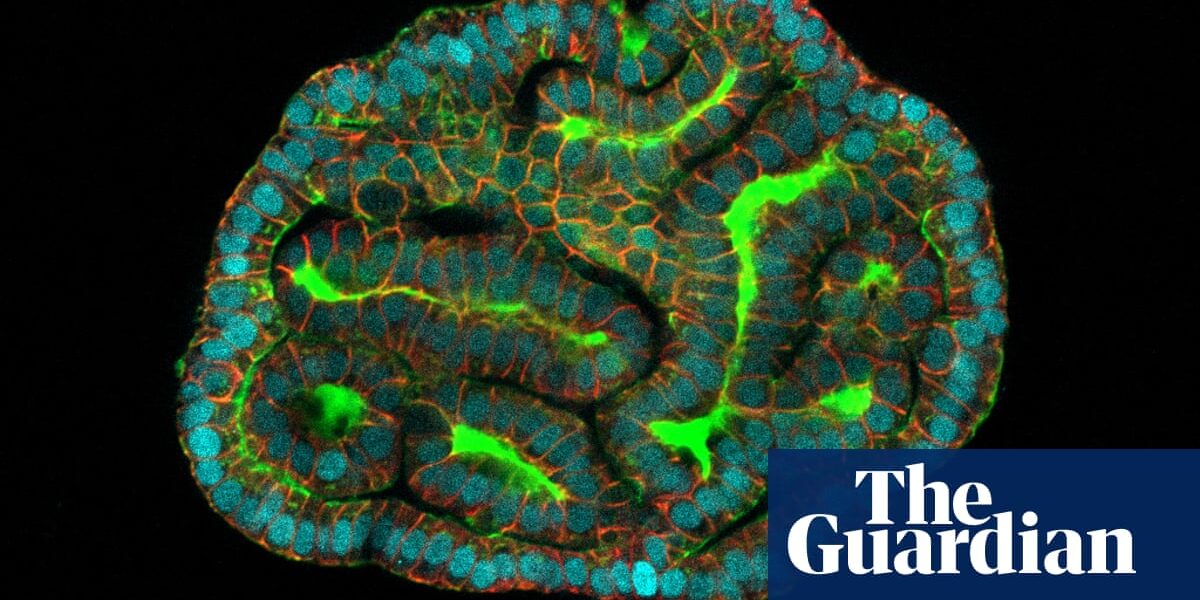

They created the 3D lumps of tissue know as organoids from lung, kidney and intestinal cells recovered from the amniotic fluid that bathes and protects the foetus in the uterus.

This is the initial instance of creating organoids using unaltered cells from fluid, opening the door to new understandings of the origins and development of deformities that impact 3-6% of newborns worldwide.

Dr. Mattia Gerli, a scientist at UCL specializing in stem cells, explained that organoids from foetuses, which have a width of less than a millimetre, provide a way for researchers to observe the development of foetuses in the womb under both healthy and diseased conditions. This has been previously unattainable until now.

Scientists suggest that creating organoids months before a baby’s birth could lead to tailored interventions, aiding doctors in identifying and treating any potential defects.

Organoids are tiny clumps of cells that mimic, to a greater or lesser extent, the features and functions of larger tissues and organs. Scientists use them to study how organs grow and age, how diseases progress, and whether drugs can reverse any damage that arises.

Organoids are typically developed using mature tissue, but there has been a recent development in using cells from fetuses. The most controversial ones come from terminated pregnancies, while others are produced by changing cells to a more embryo-like form.

In a publication in the journal Nature Medicine, Gerli and Professor Paolo de Coppi, a fetal surgeon at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, detail their examination of amniotic fluid collected from 12 expectant women during regular diagnostic procedures. Despite the majority of cells in the fluid being deceased, a small portion were identified as stem cells capable of developing into the baby’s lungs, kidneys, and intestines. Through the use of injection and culturing techniques, the team successfully grew these cells into 3D organoids in gel droplets.

The research team created lung organoids using cells from unborn babies diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). This condition is characterized by a hole in the diaphragm, a muscular structure located beneath the lungs that plays a crucial role in breathing. The presence of this hole causes organs in the abdomen to put pressure on the lungs, hindering their growth. The purpose of this experiment was to further understand the potential applications of organoids.

De Coppi noted that comparing the development of organoids from CDH infants pre and post treatment revealed significant disparities, highlighting the advantages of the treatment. This marks the first instance where a functional evaluation of a pre-natal congenital condition has been achieved.

The same approach could investigate other congenital conditions such as cystic fibrosis, which causes mucus to build up in the lungs, and malformations in the kidneys and gut. Drugs that help alleviate congenital disorders could be tested on the organoids before giving them to the babies, De Coppi said.

Roger Sturmey, professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Hull, said the research paved the way for scientists to study how key organs formed and functioned in unborn babies without tissue donated to research after an abortion. “It may also reveal early origins of adult disease,” he said, “by highlighting what happens when the cells of key tissues within foetuses malfunction”.

Source: theguardian.com