S

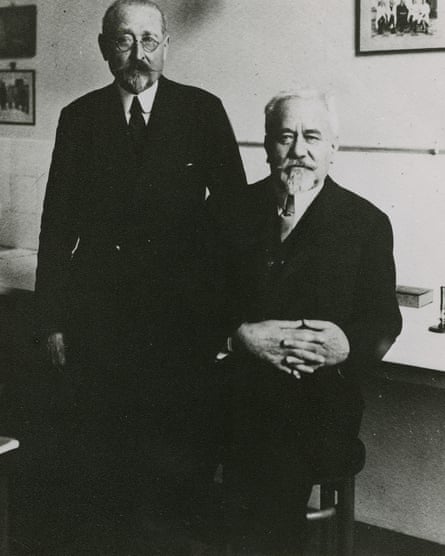

Sometimes, unexpected sources can lead to new scientific findings. In France during the early 1900s, a doctor named Albert Calmette and a veterinarian named Camille Guérin were determined to uncover the method of transmission for bovine tuberculosis. Their first step was figuring out how to grow the bacteria, which they discovered could be done using sliced potatoes mixed with ox bile and glycerine. This unconventional combination proved to be the ideal medium for their research.

As the bacteria multiplied, Calmette and Guérin were amazed to discover that with each new generation, it became less harmful. When animals were infected with the microbe that had been grown through multiple generations, they no longer fell ill, but were instead immune to wild TB. In 1921, the duo tested this potential vaccine on a human patient for the first time – a baby whose mother had recently passed away from the disease. The vaccine was successful, resulting in the creation of the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine which has saved countless lives.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Calmette and Guérin could have never imagined that their research would inspire scientists investigating an entirely different kind of disease more than a century later. Yet that is exactly what is happening, with a string of intriguing studies suggesting that BCG can protect people from developing Alzheimer’s disease.

If these initial findings are confirmed in medical experiments, it could potentially be a highly affordable and powerful tool in our battle against dementia.

The World Health Organization reports that currently 55 million individuals suffer from dementia, with roughly 10 million new cases annually. The most prevalent type is Alzheimer’s disease, which makes up 60%-70% of all cases. This disease is marked by the build-up of a protein known as amyloid beta, which leads to the death of neurons and damage to the connections between brain cells.

The cause of plaque development has long been a mystery, but various evidence suggests issues with the immune system. In our youth, our immune system is able to protect the brain from harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungi. However, as we age, its effectiveness decreases, potentially allowing microbes to enter neural tissue. According to one theory, amyloid beta is produced as a temporary defense against these invaders. Ideally, the brain’s own immune cells, called microglia, would be able to remove the protein once the threat has passed. However, in cases of Alzheimer’s disease, these cells may not function properly, resulting in widespread inflammation and further damage to the brain.

There is now abundant evidence that supports this theory. Post-mortem examinations have shown that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease tend to have higher levels of common microbes, such as the herpes simplex virus which causes cold sores, in their brains. Importantly, these microorganisms are often found within the amyloid protein, which has been shown to have the ability to fight against microbes.

If this hypothesis is accurate, efforts to enhance the overall effectiveness of the immune system could potentially prevent the onset of the illness.

Novel methods are undoubtedly necessary. Despite years of studying methods to eliminate the build-up of plaques, only two novel medications have been endorsed by the US Food and Drug Administration. These medications utilize antibodies to attach to amyloid beta proteins, stimulating an immune response that removes them from the brain. While this may slow the progression of the disease in certain patients, it frequently has a limited impact on their overall quality of life.

The use of anti-amyloid antibodies is accompanied by a significant expense. Marc Weinberg, a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston who studies Alzheimer’s, points out that the high cost of treatment may result in a large disparity in healthcare access for individuals in lower-income nations. (He stresses that his views are his own and do not represent those of his institution.)

Is it possible for current vaccines like BCG to provide a different option?

T

Although it may seem implausible, numerous studies have demonstrated that BCG can provide unexpected and extensive advantages beyond its intended use. In addition to its effectiveness in preventing TB, it appears to decrease the likelihood of various other infections. A recent clinical study revealed that individuals who received BCG were half as likely to develop a respiratory infection within the next year compared to those who received a placebo.

BCG is commonly utilized as a traditional therapy for various types of bladder cancer. When the weakened bacteria are introduced to the affected area, they activate the immune system to eliminate the tumors, which were previously undetected. According to Professor Richard Lathe, a molecular biologist at the University of Edinburgh, this can lead to impressive recoveries without any signs of disease.

These impressive outcomes are believed to arise from a process known as “trained immunity”. Following administration of the BCG vaccine, alterations can be observed in the expression of genes related to the production of cytokines – small molecules that can activate our immune defenses, such as white blood cells. As a result, the body is better equipped to respond to a potential threat, whether it be a virus, bacteria, or abnormal cell growth. According to Weinberg, this can be compared to upgrading a building’s security system to be more prompt and effective in defending against not only known dangers, but also any potential intruders.

It is believed that trained immunity may have the potential to lower the chances of developing Alzheimer’s. By strengthening the body’s defense system, it could prevent pathogens from reaching the brain. Additionally, it may stimulate the brain’s own immune cells to more efficiently remove amyloid beta proteins without harming healthy neural tissue.

Research on animals suggests that there is some preliminary proof. When laboratory mice were given BCG vaccinations, they showed decreased inflammation in the brain. As a result, their cognitive abilities improved significantly, while other mice of the same age experienced a decline in memory and learning abilities. However, it is uncertain if these findings would hold true for humans.

Ofer Gofrit and his team at the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Centre in Jerusalem studied 1,371 individuals who were either treated with BCG or not as part of their bladder cancer treatment. They discovered that only 2.4% of the BCG-treated patients developed Alzheimer’s in the next eight years, while 8.9% of those who did not receive the vaccine developed the disease.

After the study was released in 2019, different scientists have reproduced the conclusions. As an example, Weinstein and his team analyzed the medical records of approximately 6,500 individuals with bladder cancer in Massachusetts. They made sure to carefully match the age, gender, ethnicity, and medical history of those who had and had not received the BCG injection. The results showed that those who had received the injection were significantly less likely to develop dementia.

The degree of protection provided varies among studies, as a recent meta-analysis found an average decrease in risk of 45%. If this can be confirmed through additional research, the impact would be significant. Professor Charles Greenblatt of Hebrew University in Jerusalem, a co-author of Gofrit’s initial paper, states that even a small delay in the onset of Alzheimer’s could result in substantial savings in both human suffering and financial costs.

P

It is important to exercise caution. Previous studies have only focused on patients with bladder cancer and there is limited information on the overall population. One possible approach could be to compare individuals who were vaccinated with BCG during childhood to those who were not, but the protective effects of BCG may diminish over time – well before the age when most people would be at risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

However, we can analyze the impact of different vaccines given to older individuals. BCG, which contains live but weakened bacteria, is believed to provide the most effective immune training, but other vaccines may also activate the body’s defenses. For example, the flu vaccine. A recent study by Nicola Veronese and colleagues from the University of Palermo in Italy examined the results of nine studies that took into account various lifestyle factors such as income, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, and hypertension. The team discovered that the influenza vaccine was linked to a 29% decrease in the risk of developing dementia. “Two studies also showed a correlation between the number of previous doses and the incidence of dementia,” Veronese states.

These types of studies are unable to establish a cause and effect relationship. According to Jeffrey Lapides from Drexel University College of Medicine in Pennsylvania, there may be a hidden variable in this type of epidemiological research that is not being adequately considered. However, he does acknowledge that the potential influence of vaccines on dementia should be further investigated.

The clinching evidence would come from a randomised controlled trial in which patients are either assigned the active treatment or the placebo. Since dementia is very slow to develop, it will take years to collect enough data to prove that BCG – or any other vaccine – offers the expected protection from full-blown Alzheimer’s compared with a placebo.

Scientists are now investigating specific biomarkers that indicate the early development of diseases. This was previously a challenging task due to the high cost of brain scans, but advancements in experimental techniques now enable scientists to isolate and quantify amyloid beta proteins in blood plasma. These levels can serve as a reliable indication for future diagnoses.

A small preliminary research conducted by Coad Thomas Dow and his team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reveals that BCG injections may effectively lower plasma amyloid levels, especially in individuals with gene variants linked to a greater susceptibility to Alzheimer’s. Despite its limited number of participants (49 in total), the study raises optimism for the potential of immune training in combating this disease. Weinberg, who was not part of the study, expresses positivity towards these findings.

Weinberg has his own grounds for optimism. Working with Dr Steven Arnold and Dr Denise Faustman, he has collected samples of the cerebrospinal fluid that washes around the central nervous system of people who have or have not received the vaccine. Their aim was to see whether the effects of trained immunity could reach the brain – and that is exactly what they found. “The response to pathogens is more robust in specific populations of these immune cells after BCG vaccination,” says Weinberg.

Hopefully, these initial findings will encourage more studies. According to Weinberg, it’s straightforward. “The BCG vaccine is widely available and safe,” he states. Additionally, it is significantly more affordable compared to other options, costing only a few cents per dose. Even if it provides only minimal protection, he asserts that it is the most cost-effective choice.

More than 100 years ago, Calmette and Guérin unexpectedly made a breakthrough with potato slices, showing that progress can happen at unexpected moments.

The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life by David Robson is published by Canongate (£10.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Do you have any thoughts on the topics discussed in this article? If you would like to email us a response of 300 words or less to potentially be published in our letters section, please click the link provided.

Source: theguardian.com