I

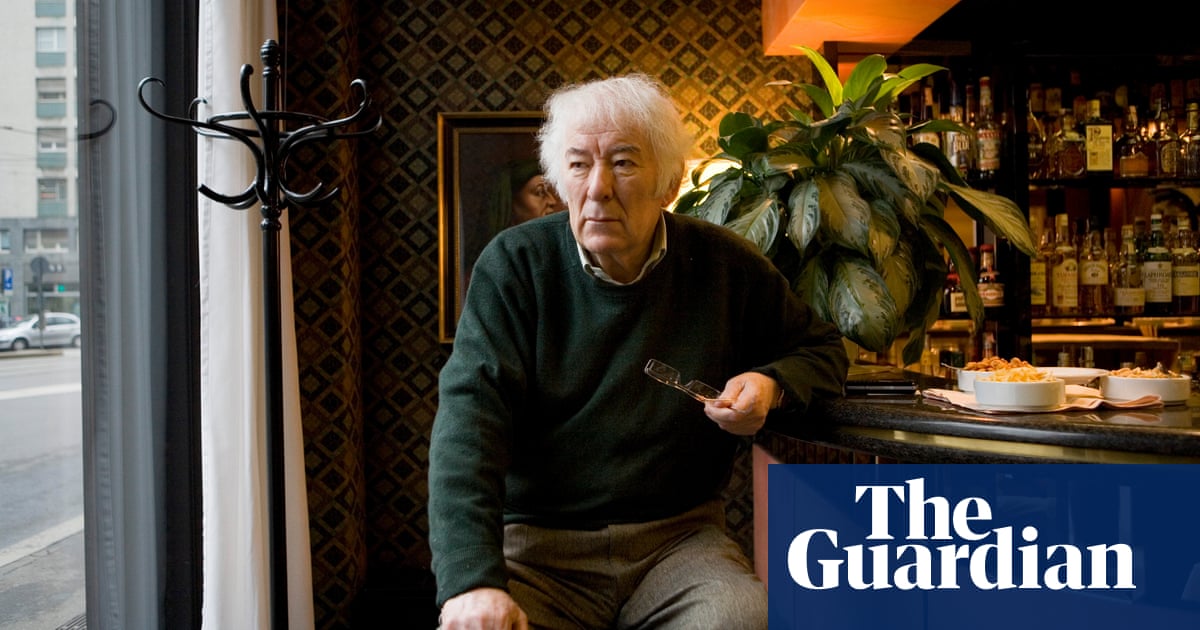

If the act of composing letters can be considered an artistic skill, then Seamus Heaney could be considered a master in this form. Christopher Reid has compiled an 800-page collection from what he claims to be a vast amount of work, stating that he had to significantly reduce the content in order to create a publishable book. This selection is not only a literary testament, but also a treasure trove of enjoyable pieces.

Heaney’s skill in prose was equal to his mastery in verse, evident to readers through his essays, articles, and extensive memoir, Stepping Stones. The memoir was compiled in the form of interviews with poet Dennis O’Driscoll. Despite the letters being written hastily, the style is impressive and consistently graceful. One of Heaney’s correspondents described him as someone who could make even the most basic words shine.

Although he may have occasional rough moments, his kindness and passion for the work of others are truly noteworthy. In 2006, he wrote to Carol, the wife of Ted Hughes, about the poet’s posthumous collection of Selected Translations. His use of a sustained oceanic metaphor is particularly beautiful: “The joys are like dolphins, the powerful talent resurfacing and revealing itself above the chaos… I acquired [the book] and immersed myself in the various bays and caverns, finding refuge in a few and exploring unfamiliar shores. I felt as though I was being carried by the tide of it all.”

Heaney could not have had a better editor than Reid. The task was surely enormous, but Reid fulfils it with a Heaneyesque diligence and scrupulousness. The choice of letters is never less than apposite, the scholarly apparatus discreet to the point of invisibility, and the endnotes to each letter are kept to a minimum.

Regarding this final aspect, Reid notes that Heaney’s life, both as a man and a poet, required extensive footnotes to accompany it. However, despite the busy appearance, there is no sense of chaos. Reid’s approach is to keep the letters themselves easy to read, and provide any necessary explanations at the end in just a few concise lines. This results in a clean and enjoyable text for both the reader’s eyes and mind.

Reid wisely avoids the immature correspondence, which was likely abundant due to Heaney’s status as a boarding school student. The initial letter is dated December 9, 1964, when Heaney was 25 years old, and is directed towards his lifelong friend and fellow student at St Columb’s College in Derry, the poet and academic Seamus Deane – who often joked that most Americans believed his name was Seamus Deaney. During this period, Heaney was awaiting news on whether the Dolmen Press in Dublin, the premier publisher of poetry in Ireland, would accept his first collection titled “Advancements of Learning.”

Dolmen declined the poems, but expressed interest in seeing more. However, at that point, Faber had already reached out to Heaney and became his English publishers for the remainder of his career. As we can see, fate had already intervened in his favor. How many young poets are given the opportunity to submit their early works to the most prestigious publishing company in this region?

Heaney’s letter to Deane begins with an apology for his delay in responding, a pattern that occurs frequently. He explains that his guilt over this matter has grown into a neurosis, unintentionally foreshadowing future events. Apologizing and attempting to catch up would become a recurring theme in his correspondence throughout his life. This begs the question if there was a persistent factor in his psychological makeup that both weighed him down and drove him forward. His strong sense of responsibility, dedication, and perpetual feeling of indebtedness never seemed to diminish.

According to numerous letters, it is evident that he was overly generous and easily accessible to those in his inner circle, as well as to others who were not as close. This behavior continued even as his fame and following grew exponentially. A friend jokingly referred to him as the person who couldn’t refuse anyone. In his later years, he became so renowned, that he was given the nickname “Famous Seamus” by cynical individuals at local pubs. His appearances at literary gatherings often caused chaos, and a letter included in this collection is from a woman whose daughter sustained injuries while trying to catch him at an event.

Repeatedly, he references lines from Philip Larkin’s poem Afternoons, where the poet reflects on young mothers at a playground and the feeling of being pushed to the sidelines of their own lives. He applies this idea to his own situation, acknowledging the success he had achieved but also the weight it brought. At only 56 years old, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1995. Years later, he wrote to his friend and fellow Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer and his wife, admitting that the prize came too early in his life and that he initially denied its impact for about a decade. However, the recognition does not fade over time and he realizes that many opportunities to speak, read, or travel are more about the “N word” (Nobel) than his own work. In a letter at the start of 2013, Seamus’s wife Marie shared that he once described receiving the prize as being “hit by a mostly benign avalanche.”

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

In the beginning of 2010, his public persona as the cheerful “Yeatsian man” finally led to his downfall. On May 30th of that year, he wrote to his friend Seamus Deane, admitting that he had been in a slump for some time. He had not been writing and had lost his confidence. However, he was able to overcome this depression, just as he had done four years earlier when he recovered from a stroke. His friend, playwright Brian Friel, who had also suffered a stroke, greeted him in the hospital with the phrase: “Well, Seamus, everyone has their own struggles, right?”

He was lucky to have such supportive friends, evident in the sincere affection conveyed in their letters. However, his family held a special place in his heart, including his parents, siblings, and later, his beloved wife and three children. Marie Heaney, a writer and scholar, was his constant support and he often mentions her in these letters, seeking her guidance and wisdom. As he wrote to Seamus Deane in 1966, Marie, whom he had wed the year before, had playfully referred to him as the “laureate of the root vegetable”.

This book is wonderful, carefully edited, and visually appealing – the paper quality is exceptional, a rarity in modern times. It is full of literary analysis, humorous moments, a touch of gossip, and the poet’s unwavering joy for life, even during difficult times. Purchase it, read it, and pass it down to your children.

Source: theguardian.com