The title of Hannah Regel’s assured debut novel presumably alludes to Angela Carter’s description of the potter Michael Cardew as “the last sane man in a crazy world”. Two of Regel’s three female characters are aspiring ceramicists. Neither achieve Cardew’s fame. The Last Sane Woman is a study in artistic endeavour, disappointment and envy.

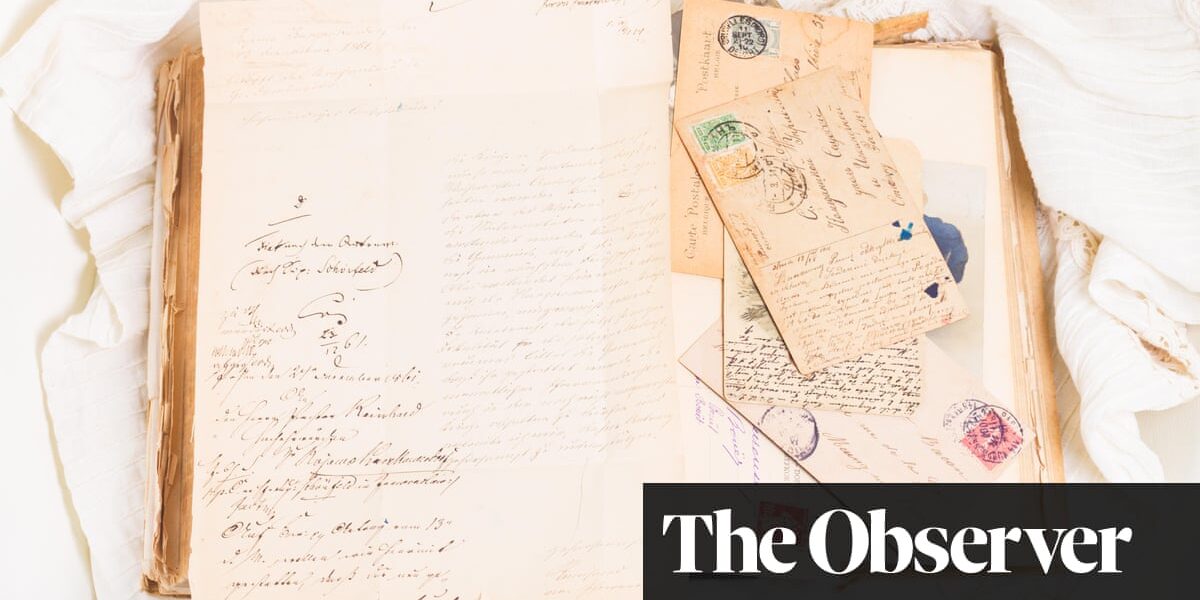

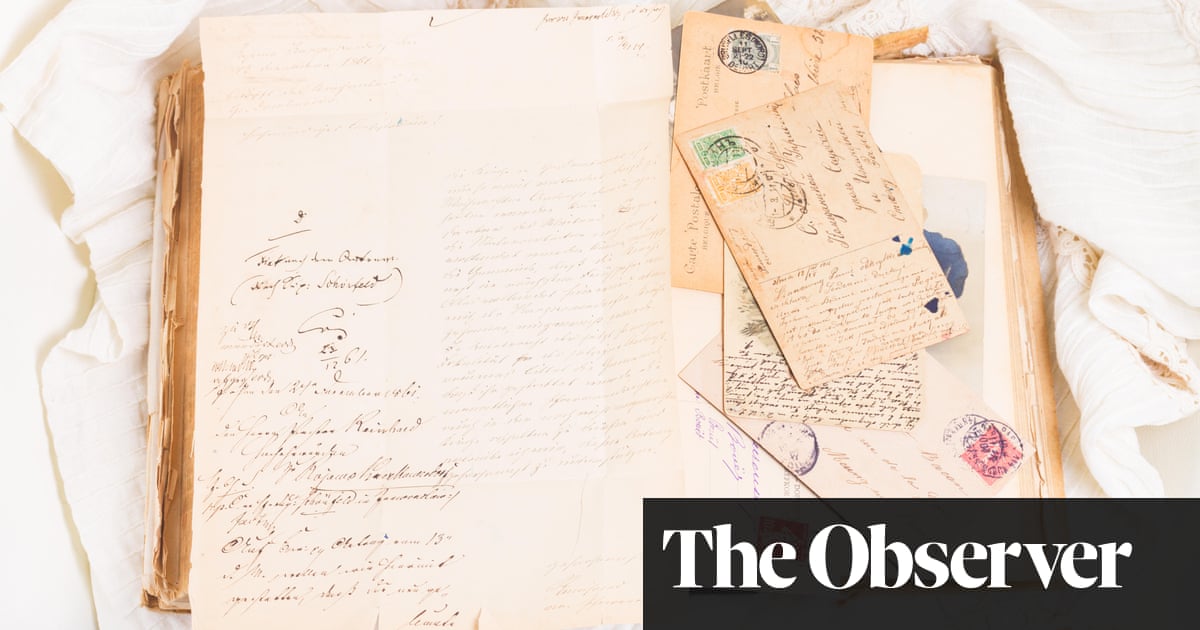

Nicola has a bachelor’s degree in sculpture and dreams of becoming a successful artist. Instead, she works as a nursery nurse, “posting photographs of the objects she’d made to the internet with the same fervour as she posted her face”. When she discovers the Feminist Assembly, “a small, underfunded archive dedicated to women’s art”, she becomes obsessed with the letters that ceramicist Donna Dreeman wrote to her best friend, Susan Baddeley, in the 1970s and 80s, before she took her own life (Susan’s is the third perspective).

Nicola is initially exhilarated to read of Donna’s daily disappointments, dead-end jobs, failed love affairs and artistic frustrations; the mutual recognition that the creative industries favour those with wealth and good connections: “This was exactly how she felt. The thrill pulled a thread across her chest; Nicola wasn’t just overhearing, she was being overheard.” But this is overtaken by a creeping dread that their lives are irretrievably entwined.

Formerly the co-editor of the feminist art journal SALT, Regel clearly knows this milieu, and decadent gatherings are depicted with wry humour. Regel is also a poet and delights in language, though her style is occasionally too ornate for my tastes. Take this description of entering a pub after a snow blizzard: “The relief is palpable: it knocks them off the polar bear’s back and sucks them into its innards, where the deep red Lincrusta ceiling looks ready to drip.”

The various periods, settings and large cast of minor characters are occasionally disorientating. But Regel understands the fine line between success and failure, the difficulties of producing meaningful art in a fickle world, and her book is a sensitive meditation on creativity and disconnection.

Source: theguardian.com