The creators of The Simpsons, a combination of hippies, nerds, and Hollywood professionals, hoped to infiltrate the media with their project.

I

In a previous episode of the first season of The Simpsons, Homer can be seen browsing through a publication titled The Bowl Earth Catalog. This is a clever play on words referencing the famous counterculture book of the 1960s, the Whole Earth Catalog. This book was known for promoting west coast environmentalism, do-it-yourself projects, and dreams of a tech-based utopia, although it also subtly encouraged consumerism. The inclusion of this reference is a subtle detail that may go unnoticed, but it provides a glimpse at the origins of The Simpsons.

During the early 1980s in Los Angeles, cartoonist and comic strip artist Matt Groening was in the process of creating a show. At this time, the hippy counterculture was becoming older and wealthier. The younger generation had embraced the emerging alternative culture of punk and new wave music, as well as various forms of self-expression such as alternative newspapers, self-published magazines, and underground comics. Regardless of the label, a do-it-yourself mentality was still prevalent.

It is difficult to believe how much The Simpsons has changed from its origins as a huge franchise filled with merchandise during the popularity of the character Bart, to its reign in the 1990s, and its impressive longevity spanning two additional decades with a film and a series of groundbreaking episodes.

A video on YouTube shows that the foundations were simpler and more crude in the past. In the video, Matt Groening introduces his friend, artist Gary Panter, at a book event in Los Angeles in 2008. He references the Rozz Tox Manifesto, which was published by Panter in 1980, and reads out one of the 18 commandments. Groening reveals his personal favorites, including item 12: “Waiting for art talent scouts? There are no art talent scouts. Face it, no one will seek you out, no one cares.” Item 15 states, “If you want better media, go make it.”

View the image in full screen mode.

Panter expressed his enthusiasm for sharing his work while speaking on the phone from his residence in Texas. He and his partner both had a strong desire to make their mark in the media industry.

Panter, who is a painter, illustrator, musician, and more recently, a creator of bracelets, first published his satirical manifesto in fragments on the free personals section of the Los Angeles Reader. The Los Angeles Reader was an alternative weekly newspaper established in 1978. His manifesto served as a rallying cry of sorts, blending elements of the avant-garde and popular culture, as well as bringing together those on the fringe and those in the mainstream to create something new within the existing system. There was a small community of individuals who shared Panter’s ideas. “It mostly consisted of art students, unattractive and unpopular kids,” Panter fondly remembers.

At around the same time, Groening, who was then an aspiring artist for comics and had recently relocated to LA from the Pacific Northwest, began self-publishing his comic strip called Life in Hell. The strip, featuring witty observations and anthropomorphic rabbits, received recognition and praise. Meanwhile, Groening was working at a Licorice Pizza record shop, which was later featured in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2021 film. According to Panter, Life in Hell was a clever and minimalist creation, which inspired him to write a fan letter to Groening. The two met at a party and bonded over their mutual admiration for artists Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart. Despite both being financially struggling, they became friends and would often share resources, including splitting the cost of hamburgers.

Groening and Panter collaborated on comics for punk zines under names including the Fuk Boys. Byron Werner (who went on to a long career in Hollywood visual effects) was also among their LA set, self-publishing comics, while the influential cartoonist Linda Barry was a friend of Groening’s, “so out of that came this giant explosion of mini comics across the country in the next few years. There was a lot percolating at the same time,” Panter says.

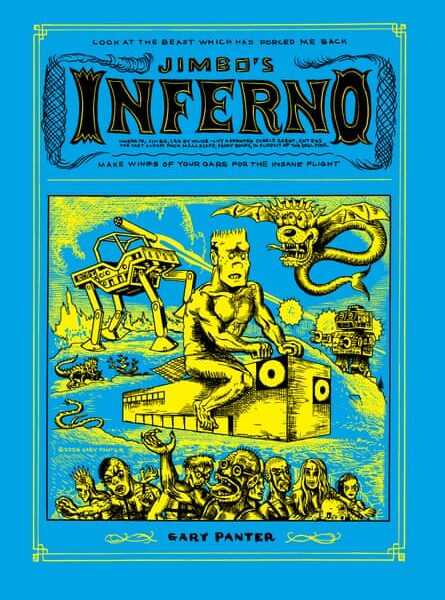

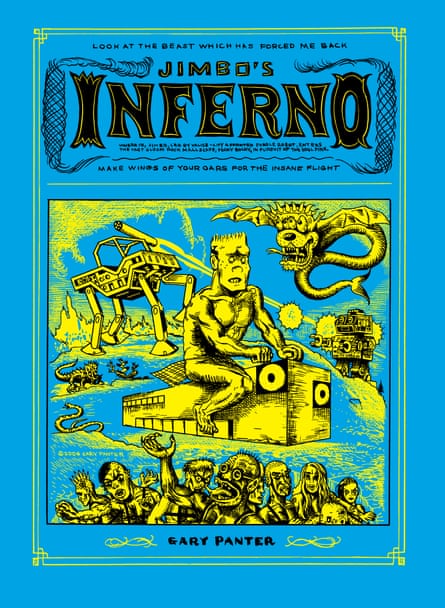

Groening continued with his weekly Life in Hell strip, eventually syndicated widely in alternative papers – and, improbably, he kept it going until 2012 despite his vast television commitments. One of Panter’s signature antihero characters, Jimbo, complete with spiky hairdo, is credited by many, including Groening, as an inspiration for Bart Simpson. “He’s said that. I think he’s being kind,” Panter demurs.

Panter achieved mainstream success in 1986 when he began designing colorful and surreal sets for Pee-wee’s Playhouse on television. However, he left the show after three years feeling exhausted by the experience. According to Panter, his collaborator Matt was more suited for working in the mainstream. Panter himself wanted to focus on his passion for painting and cartooning, as he saw himself as more of an artist than a mainstream designer. Both Panter and Matt had fathers who pushed them to succeed, leading them to constantly strive for greatness.

Soon after, Groening would join Panter in venturing into television, thanks to Polly Platt. The often-overlooked producer, production designer, and writer presented James L. Brooks with an original artwork from Life in Hell. Brooks, who had worked on popular shows such as The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi, as well as the movie Broadcast News, played a crucial role in helping Groening transition from an underground comic strip to creating snarky TV sketches and eventually, a globally recognized sitcom.

What made this time unique was the fact that The Simpsons’ sensibility made its debut in primetime television. The show combined Groening’s unconventional cartoon style with the quirky and sarcastic humor of writers from Saturday Night Live and David Letterman.

Bill Oakley, who, along with his writing partner Josh Weinstein, joined the esteemed writing room of The Simpsons in 1992, recalls that primetime TV viewers were not accustomed to that style of humor. It may be difficult to believe now, but nearly 70% of television shows possess that same sensibility. However, during that time, the majority of comedies were rather vanilla and unexciting.

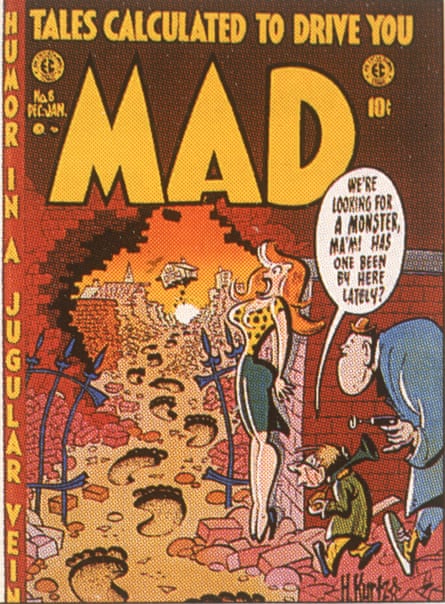

During its time, The Simpsons stood out among other safe sitcoms like The Cosby Show and Mad About You. The writers were influenced by Mad magazine, a beloved childhood classic, as well as Fox’s Married… With Children, which had a rebellious and irreverent tone. They also drew inspiration from the 1960s sitcom Green Acres, a less popular reference in the UK. The show’s boldness and tendency to break the fourth wall aligned well with The Simpsons’ brand of humor.

National Lampoon and Harvard Lampoon were closely connected as sources for alternative comedy. SNL followed the template set by National Lampoon, while many writers for The Simpsons came from Harvard Lampoon. This lineage was so prominent at The Simpsons that it became somewhat annoying to others. “In the late 90s, mentioning our Harvard Lampoon background became tiresome,” says Oakley. However, being part of the Lampoon was more than just a similar comedic sensibility; it was like attending graduate school for comedy.

George Meyer was one of those who came through the Harvard Lampoon line. After college he wrote for then upstart late night chatshow host David Letterman, among other things, and on the side self-published a small humour magazine called Army Man (“America’s only magazine,” ran the tagline). It featured work from Meyer himself and future Simpsons writers including John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti and Ian Maxtone-Graham, as well as cartoonist Roz Chast and comic actor Bob Odenkirk.

Despite only being published for three issues, its influence was significant. Copies of the publication were circulated around college campuses, and there were offers to expand it into a television show. One of its admirers was Sam Simon, who recruited Meyer and other contributors for his show The Simpsons. The small magazine had a big impact on the comedic roots of The Simpsons. It is interesting to note the similarities between self-published humor magazines (Oakley and Weinstein had their own briefly) and the alternative zines and comics that Groening and Panter had previously experimented with.

During the 2000s, Meyer was an acclaimed producer with a gentle and hippy-ish mindset. He was highly praised for his work on the popular TV show, and was even referred to as “the funniest man behind the funniest show on TV” in a profile by the New Yorker in 2000. Another highly revered writer for the show is Swartzwelder, known for contributing the most episodes in the show’s history and creating beloved jokes and characters with a uniquely carnival-esque and American twist. With a reclusive nature and rare appearances in photographs, Swartzwelder has gained a legendary status among fans of The Simpsons and those who appreciate quality comedy. According to Oakley, “He was a one-of-a-kind individual, like a rare unicorn from a completely different world.”

The author of The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorised History, John Ortved, reveals that the show’s creators were not all eccentrics influenced by Zappa and Pynchon. Even the famously bizarre writer, Swartzwelder, had a past in the advertising industry. Ortved explains that the writing room was led by Sam Simon, a seasoned TV writer with experience on shows like Taxi and Cheers. While the room was young, they were not inexperienced or simply out to rebel; they were the best and brightest in the industry with credits on shows like It’s Garry Shandling’s Show and Tracey Ullman.

According to Ortved, The Simpsons stood out because of its unique combination of elements. This included the nerdy writers from Harvard, professional TV writers, creator Matt Groening’s outlook of Generation X, and the guidance of Hollywood veterans James L. Brooks and Sam Simon. Another important factor was that Fox network allowed The Simpsons creative freedom in what they produced. This was a perfect realization of the Rozz Tox Manifesto from ten years prior, which jokingly called for avant garde art to coexist with the entertainment industry. The idea was that capitalism, for better or worse, guides our successes and failures.

There is also a bittersweetness to this. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to envision a combination of such exceptional talent that could come together to produce a show as influential as The Simpsons is today. As proven by last year’s Hollywood writers’ strike, the circumstances and chances for creative individuals have only been declining. At the same time, the overall environment has also become more challenging: the alternative weeklies that used to empower people to speak out have faded away, and zines are mostly a thing of the past before the internet.

Gary Panter sometimes wonders if the underground can still exist in the age of the internet shining a half-light on anything and everything – but then remains defiant. “There still is an underground,” he says. “That’s the great thing. People are not necessarily trying to be underground but there are tens of thousands of creative people doing stuff, who aren’t just looking at the biggest projects.”

According to Panter, Raw magazine, founded by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly in 1980 to feature alternative comics, initially had a limited number of American artists involved in their preferred medium. However, there has been a significant increase in the number of artists involved since then. It is unnecessary to overly romanticize specific moments from the past, as the culture continues to thrive.

He explains, “When people ask me about the LA punk rock scene, I always think of it as going out to a club in the middle of the night to see what will unfold. This is still happening all over the country and the world.”

Disney+ offers access to The Simpsons.

Source: theguardian.com