The book “Pity” by Andrew McMillan explores the themes of masculinity and nostalgia in a mining town in Yorkshire.

A

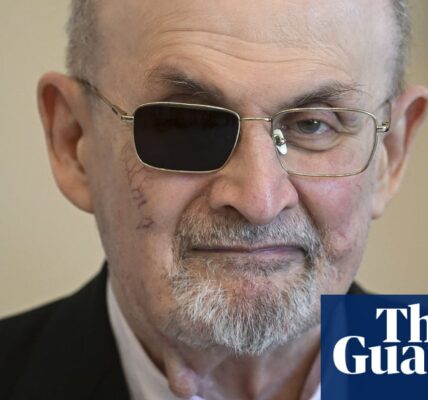

Andrew McMillan’s first book of poetry, physical, delves into the delicate yet raw exploration of masculinity in the industrialized north of England. It celebrates the experiences of young queer men in the early 2000s and was honored with the Guardian first book award in 2015. His second collection, playtime, received the inaugural Polari prize for LGBTQ+ literature and was followed by pandemonium in 2021.

Unfortunately, McMillan is using his exceptional skill to create a story. The novel, titled “Pity,” is set 40 years after the 1984-85 miners’ strike that greatly impacted the UK and caused division within working-class neighborhoods. It follows three generations of men from one family who have all been shaped by their connection to the nearby coal mine, which has since shut down following the strike. The story takes place in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, where McMillan grew up.

This is not a novel specifically about the strike and its outcome, although its embittered legacy is skilfully threaded through its pages. Pity is a book about male identity and sexuality – whether anxiously concealed or proudly open – and about the ravages of history and politics, most significantly on the working-class towns and cities of South Yorkshire such as Barnsley and Sheffield. Comprising multiple viewpoints, the narrative is impressively ambitious for a book of fewer than 200 pages.

The novel follows the perspectives of Alex and Brian, two middle-aged brothers, as well as Alex’s son Simon and his new partner, Ryan. Interwoven with their stories are accounts from anonymous bystanders and academic fieldnotes from a team studying urban memory in Barnsley. These fieldnotes provide earnest observations as the team prepares for the 50th anniversary of a disaster that occurred in the city. The novel also includes recurring poetic passages describing a group of miners leaving for work at dawn, hinting at a past tragedy that is only revealed at the end of the novel.

The story opens with a quick introduction that perfectly captures McMillan’s confident and unemotional style. It takes place in the 1970s, and the main character, Alex, is more interested in a stolen pornographic magazine than in the mysterious crisis that has caused his mother to leave the house in a hurry. His older brother, Brian, catches him engaging in self-pleasure, but does not realize that Alex is more interested in the pictures of men than women. This scene is reminiscent of the “hands off cocks; on socks” moment in Barry Hines’s well-known book, A Kestrel for a Knave. However, McMillan does not simply replicate his fellow Barnsley writer’s most famous work.

The story quickly shifts to the present, where Ryan works as a security guard at a local shopping mall and Simon has a day job at a call center. However, at night, Simon transforms into a drag queen and prepares to perform a show that will take on Margaret Thatcher. Instead of his usual venue in nearby Sheffield, he will be performing in Barnsley, where his divorced father resides and the door code is 1912 – the same year that Barnsley last won the FA Cup. The book delves into themes of ruefulness and civic pride, as well as the act of hiding and revealing oneself. This is seen in Ryan’s job as a security guard using surveillance cameras and Simon’s OnlyFans account, which makes Ryan, who plans to become a police officer, uneasy. The two men recently met on Grindr and the underlying message in McMillan’s writing is the hesitation and struggle with queerness that Ryan experiences compared to Simon, who has already embraced his identity. The damage caused by section 28 is also referenced, with Simon recalling being outed via text message at school and his father’s fear leading him to suppress his true self.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

McMillan carefully observes how Simon creates his drag persona, noting that even Margaret Thatcher herself could be seen as a form of drag: “she understood that gender was fluid, took voice lessons to deepen her voice, and paid attention to her posture.” Unemployed Brian, who initially only attends the memory project for the free sandwiches, struggles to express a past trauma that has affected both his community and personal life: “his own street was like a mouth with missing teeth.” He also acknowledges that people often have no choice but “to move on with their lives.” As a professor of creative writing, McMillan cleverly includes himself in this section as one of the academics “with an accent that seems to have originated here but blossomed elsewhere.” This highlights the fact that while some may have opportunities for social mobility, others do not.

Pity is a deeply empathetic novel, particularly towards its main characters Alex and Brian, who are former miners constantly bound by their past experiences. Despite the closure of the pits, they are still mentally and emotionally trapped underground. Yet, through their writing, they find a sense of liberation. Beneath it all lies a thick and heavy history, with its powerful effects slowly ticking away like a ticking timebomb.

Source: theguardian.com