J

Juan Diaz’s poignant and poignant autobiography evokes memories of Douglas Stuart’s award-winning novel Shuggie Bain, which depicted a fictional story in a similar setting – the Glasgow slums and glimpses of beauty contrasted with the harsh realities of poverty. Slum Boy offers vivid depictions of destitution intertwined with moments of breathtaking beauty, showcasing the author’s artistic talent in recounting his past with eloquence and sophistication. Through his skillful prose, Diaz not only escapes from his past suffering but also elevates and expands upon even the most traumatic and squalid events.

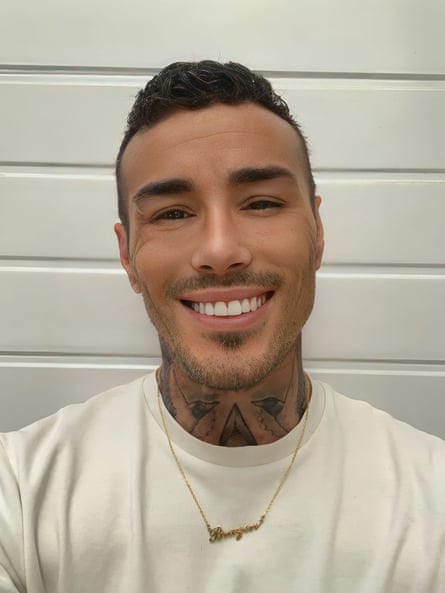

Similar to Stuart, Diaz has recently published his debut novel in his middle years. Before delving into writing, Stuart had a thriving career as a fashion designer. On the other hand, Diaz is a renowned artist and photographer who has worked alongside Gilbert and George and Grace Jones. Just like Stuart and the main character in Shuggie Bain, Diaz identifies as a gay man whose creations honor his upbringing while also surpassing the challenges of living in a society that rejected him.

The story opens with a young boy named John, who is four years old and has just returned to his mother after living with foster parents. His mother, who was unable to care for him due to her alcoholism, referred to him by his given name, but his grandmother always called him “the wee bastard.” Unlike his sisters who are in different children’s homes, John is aware of his differences – his jet black hair and olive skin, compared to his mother’s red hair and his sister Ronnie’s blond hair. He never knew his father, who was from South Africa.

Following his mother’s absence due to excessive drinking, John is taken in by a prosperous family of Travellers and relocated from Glasgow to the rural outskirts. Despite his new family’s wealth, the villages in 1980s rural Scotland struggle with poverty and a widespread heroin crisis. John becomes fluent in Scottish Cant, the language of his adoptive Roma family. His “father” is a thriving scrap metal dealer who also manages the local boxing gym, showing John tough yet genuine affection.

The story fast-forwards to John’s teenage years. He leads a double life – avoiding classes he dislikes, but also showcasing his artistic abilities with the help of a supportive teacher named Norma. At night, he sneaks out dressed as a woman and wanders around the village, imagining himself as his biological mother. This transgression brings him a sense of freedom. Although his parents are unaware of his actions, they become concerned about his growing femininity. As a result, John is sent to work at his father’s scrap yard.

John’s ultimate desire is to escape from his current situation, and the Glasgow School of Art seems to provide that opportunity. His life is a balancing act between unpleasant work environments and strained family dynamics, but also includes the thrill of attending art school and frequenting gay bars in the city. However, tragedy strikes and John finds himself pulled back into the squalor and despair of the slums he had managed to escape.

Slum Boy is reminiscent of a novel, featuring beautiful passages throughout. When John comes across a homeless man in the park, he observes the man’s appearance with poetic detail, noting how his hair flaps in the wind like a tattered flag and his arms move with a frenzied grace. The concept of time is skillfully handled, as the reader follows John through various setbacks and the author’s perspective ages alongside him. As the story progresses, the older Juano begins to offer his own retrospective commentary on John’s struggles in life. This book delves into the lasting effects of early trauma and how it can manifest in different ways throughout one’s life. As John reflects on his struggles as a young adult, we are reminded of his difficult childhood, where his feet were deformed by inadequate care home shoes. While Douglas Stuart may be the obvious comparison, I would also liken this work to Alexander Masters’s “Stuart: A Life Backwards” and Andrea Elliott’s “Invisible Child.” These are the only other nonfiction works that have moved me to such an extent.

Source: theguardian.com