Rewritten: Review of “The Men of 1924” by Peter Clark and “The Wild Men” by David Torrance – A Look at Labour’s Initial Experience with Authority in 1924

O

The pearl-clutching countess was horrified by the idea that the commoners would violently overthrow the aristocracy and seize their wealth. Sir Frederick Banbury, a septuagenarian Tory MP for the City of London, boldly stated that he would personally lead the Coldstream Guards to protect the constitution at Westminster. King George V expressed his unease in his diary, wondering what his late grandmother Queen Victoria would have thought of a Labour government. The traditional ruling classes were filled with fear and anger when Ramsay MacDonald became the first Labour prime minister one hundred years ago this month. Many of them also looked down on the Labour party, with former Liberal prime minister Herbert Asquith haughtily describing them as a “beggarly array”.

The surprise turn of events within the new cabinet was met with disbelief, especially by many of the male members who came from humble backgrounds. John Clynes, MacDonald’s deputy, felt a sense of wonder as Labour ministers were sworn in as privy counsellors at Buckingham Palace. “Amidst the opulence of the Palace, I couldn’t help but be amazed by the unexpected change of fortune that had brought MacDonald, a former clerk; Thomas, an engine driver; Henderson, a foundry worker; and Clynes, a mill worker, to this high position.” Philip Snowden, the chancellor, wrote: “It had finally happened! Many of us who had worked hard for years to achieve this goal didn’t expect to see it happen in our lifetime.”

Excitement was mixed with fear. No matter how terrible the Tories’ legacy may be for Keir Starmer, it will not be as horrifying as the state Labour faced in 1924. Britain was still recovering from the damage of World War I and there was little progress in fulfilling David Lloyd George’s pledge of “homes for heroes”. Unemployment rates were at about 10%. Strikes were prevalent in important industrial areas. The global atmosphere was tense. The majority of newspapers were controlled by conservative media moguls who were strongly opposed to Labour.

Display the image in full screen mode.

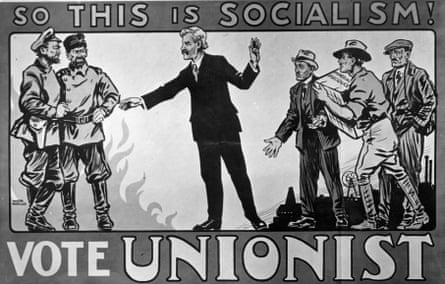

In addition, Labour held a minority position in a divided parliament where it was not the most dominant party. The Conservatives, known at the time as the Unionist party, lost their majority in the December 1923 election due to Stanley Baldwin’s misguided decision to make protection a central issue. Although they still held the largest number of seats in the Commons, they lacked the credibility and support from other parties to continue governing. The Liberals, the third largest group, chose to allow a Labour government to take control, reasoning that its tenuous hold on power meant it could easily be ousted by its opponents. Asquith told his fellow Liberals, “If we are ever going to try a Labour government in this country, it could not be done under more secure circumstances.”

With only 191 MPs, Labour held less than one-third of the seats in the Commons. There was concern among many that they would be “in office, but not in power”. MacDonald had previously stated that forming a government without a majority would be irrational. However, when the opportunity for power presented itself, he changed his stance, believing that Labour needed to demonstrate its capability to govern and fulfill his goal of permanently replacing the Liberals as the main rival to the Tories.

This was a significant turning point in the social makeup of Britain’s leaders. Peter Clark’s fascinating and informative retelling is especially effective in highlighting the stark differences between the new cabinet and its predecessors. It was a clear departure from previous Conservative and Liberal governments, which were dominated by the wealthy aristocracy and middle class professionals. MacDonald, the illegitimate son of a ploughman and maidservant, led the cabinet. Most members had left school by the age of 15, and many had started working at a young age in various manual labor jobs such as mining. This was a striking contrast to the outgoing Baldwin cabinet, where most members had attended either Eton or Harrow. While no women were included in the cabinet, junior minister Margaret Bondfield broke through the glass ceiling and became the first female minister in a British government.

MacDonald was not aligned with the Bolsheviks, despite being accused by his opponents. He had a fondness for aristocrats and had a positive relationship with the monarch. The king believed it was important to give Labour a fair chance at governing, while MacDonald believed his party needed to appear respectable to gain support from those in the middle. This caused conflict with more radical members of the party, such as the “Clydesiders.” One indication of this tension was disagreements about appropriate attire when meeting with the king. As George V placed great importance on ceremonial matters, he expected his new ministers to wear court dress, with a minimum requirement of a frock coat and silk hat when visiting the palace.

The secretary of the king sent a letter to the Labour party’s chief whip informing them that the outfit could be purchased for £30 at Moss Bros, which was considered a large sum of money for many of the Labour members. A socialist magazine in Glasgow released a picture of Labour government officials wearing top hats with a sarcastic caption questioning if this was what the voters had supported.

Historians have largely overlooked Labour’s initial experience in power, as they often focus more on MacDonald’s second term in office starting in 1929 and his later choice to form a coalition with the Conservatives. This decision has solidified his place as the ultimate enemy in Labour’s list of betrayers to their cause. However, the government in 1924 is finally receiving the recognition it deserves through these captivating books.

David Torrance presents a clear and well-written account of the events through a series of biographies of the key players, an effective method for navigating a tumultuous time. The summer of 1924 was a highlight for MacDonald, who served as both foreign secretary and prime minister. He successfully diffused tensions over German war reparations at the London conference. Despite their lack of experience, the majority of the cabinet had performed admirably and earned the respect of their colleagues and rivals. While there was no scientific way to gauge a government’s popularity at that time, their budget was well-received and they were generally well-liked by the public.

Suddenly, everything fell apart. Rivals from the Tory and Liberal parties had become intolerant of the Labour government and took advantage of opportunities to exploit the “red bogey” in order to bring it down. The government’s decision to lend money to the USSR, partly in hopes of getting Russia to compensate British asset owners who lost their property during the revolution, was heavily criticized. The final blow came with the “Campbell Case”. The government foolishly pursued charges of sedition against a communist journalist who had a distinguished war record, but then hastily dropped the case. This sparked outcry and the Tories and Liberals united to overthrow the Labour government after just nine months in power. During the subsequent election, the “red scare” was intensified by the fraudulent publication of the Zinoviev letter in the Daily Mail, which falsely claimed to be from a Soviet leader calling for a Bolshevik-style revolution in Britain. As a result, the Conservatives regained power with a massive majority.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Was it all for nothing? James Maxton, a discontented Scottish left-wing politician, expressed his frustration that each day in office brought them further away from socialism. Beatrice Webb, known for her snarky remarks, criticized MacDonald for only pursuing conservative reforms. Historians who have studied this time period have determined that the accomplishments of the 1924 government were minimal due to their short time in power.

Torrance argues convincingly that this approach is too severe. The implementation of full-fledged socialism, including a wealth tax and the nationalization of mines and railways, was ultimately abandoned due to a lack of support from Parliament. The radical politicians of 1924 did manage to make some progress towards a more civilized society by increasing the wages of farm workers and promoting better education for less affluent children. However, their most significant contribution was the ambitious plan led by John Wheatley to build affordable housing for working-class families living in deplorable slums. This initiative was continued by subsequent governments and established a bipartisan agreement that the government had a responsibility to provide public housing, which remained in effect for fifty years.

In the 1924 election, there was a notable increase of over a million votes for the Labour party. However, the Conservatives were able to secure their position as the winning party because their vote doubled that of Labour’s. The most noteworthy aspect of this election was the significant decrease in support for the Liberal party. Despite any other criticisms, it can be argued that MacDonald achieved his goal of positioning Labour as the main opposition to the Tories and paving the way for future reforms, which would not come until over two decades later with the Attlee government.

The significance of the 1924 government lies not only in its accomplishments, but also as a symbol for the future.

.

Andrew Rawnsley serves as the Chief Political Commentator for the Observer.

The book “The Men of 1924: Britain’s First Labour Government” written by Peter Clark is available for purchase at Haus for £20. You can also support the Guardian and Observer by ordering your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Additional fees may apply for delivery.

Source: theguardian.com