R

Roland Allen has a strong affinity for notebooks, which is understandable as he is a writer. In his latest work, aptly titled “A History of Thinking on Paper,” he asserts that for those whose livelihood revolves around words, a notebook can serve both as a medium and a reflection of oneself. This sentiment was also shared by Paul Valéry, who was just as passionate about his notebooks as he was about his symbolist poetry, for which he is renowned. Valéry made it a daily ritual to wake up early and write in his notebooks for 50 years, resulting in a total of 261 books. He believed that by devoting his mornings to the pursuit of intellectual stimulation, he earned the right to be less intellectually demanding for the rest of the day.

Notebooks have existed in various forms since at least the late 13th century. In Florence, they were utilized as ledgers and contributed to the advancement of double-entry bookkeeping. Additionally, their use of paper, instead of the pricier and less durable parchment, played a crucial role in the growth of mercantilism. As sketchbooks, they enabled artists to repeatedly capture their surroundings and refine their techniques for a more lifelike depiction.

There also emerged rapiaria – grab-bags of pious phrases taken from scriptures. And zibaldoni – collections of recipes, ballads, prayers and personal information that could be shown to friends and even continued by relatives. This latter practice could backfire; Allen cites a zibaldone in which someone, possibly the writer’s brother, has added: “Note that you are lying through your teeth like the scoundrel you are, and you are a crazy windbag.”

There were various items such as memoirs, journals, notebooks, and quarter sheets of paper. Additionally, there were autograph books, self-assessment books, lists of acquaintances, and climate records. One notable item was a 410-page book about fish created by Adriaen Coenen. Its detailed illustrations and information about fishing locations and marine creatures were so impressive that people paid more to read it at a Leiden fair than to see real fish.

A particularly eerie section discusses LHD 244, a musical document utilized by numerous singers and musicians between the 15th and early 17th centuries. Over time, it became worn and marked, changing hands and accumulating knowledge and nuances along the way. It was a constant presence for a series of childless Franciscans, who lived and passed away as a community within their order. Perhaps it came to symbolize the relationships that formed between teachers and students as they collaborated to create music for the glory of God.

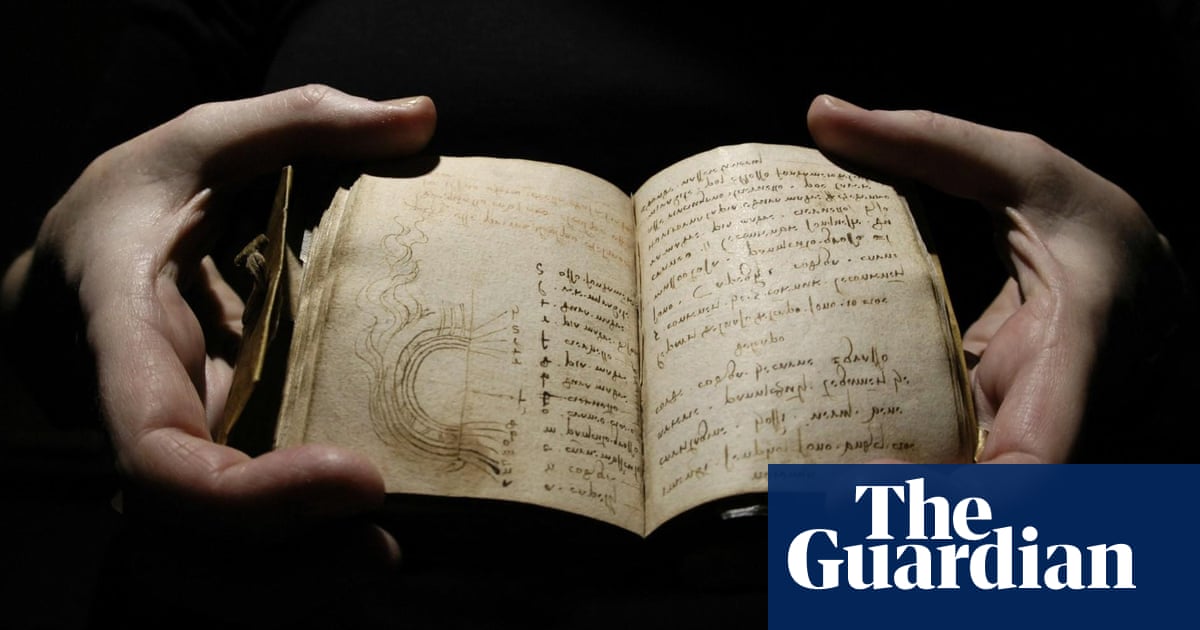

Possibly the most celebrated notebooker of all was Leonardo da Vinci. Every day he scribbled, doodled, diagrammed. He filled thousands of pages with sketches of waves, bubbles, vortices; designs for pumps, valves, furnaces, grinders; closely observed chins, vertebrae, feet bones. He made lists – 67 different words to describe the ways in which water moves. He explored geometry, anatomy, mechanics, colour itself. Speculative as much as forensic, he imagined prefabricated mobile homes and flying machines. The books themselves are almost airborne with possibilities, dreaming, gleeful experimentation.

The enduring appeal of notebooks lies in their ability to capture movement and freedom. They are often filled with direct observations, primary information, and pre-theorized experiences. Some may consider this to be a form of authenticity. Musician Brian Eno even came up with the idea that NOTEBOOKS could stand for “Nothing On This Earth Betrays Our Own Karakter So.” Author Allen references 18th-century Dutch woman Magdalena van Schinne, who started her journal with the intention of pouring out her soul. However, not all notebooks can be deemed reliable; one section explores how police pocketbooks have been tampered with, falsified, or withheld from official investigations, such as in the case of the Hillsborough disaster.

Unfortunately, cursive writing is often neglected in modern school curriculums. This is a shame. Allen presents evidence that using pen and paper to take notes is the most effective way to process and retain information. It can also help prevent depression and provide stability for those struggling with ADHD. Writing by hand is a tactile experience that falls under the concept of “embodied cognition”, further showcasing the benefits of taking things slow. In a touching chapter titled “In Search of Lost Time”, the author pays tribute to Danish nurses in ICU units who started patient diaries to document the physical changes and progress of individuals who had lost their sense of self due to illness. This act of attentive care, combined with the act of handwriting, is a true expression of love.

Move past promotional email for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Source: theguardian.com