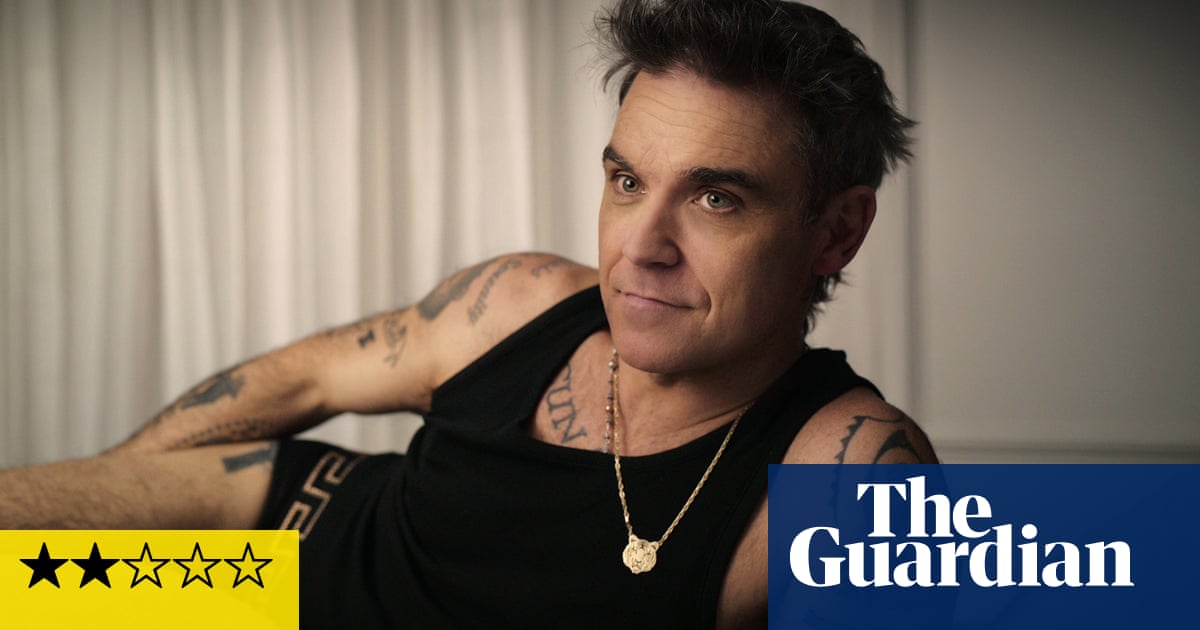

Review of Robbie Williams – a four-hour performance of dark introspection from the mega-celebrity in his underwear.

R

Robbie Williams is currently not wearing pants while sitting on his bed in his mansion in LA. He is watching footage of himself from previous years on a laptop. The footage includes behind-the-scenes moments from his time with the band Take That, as well as his successful solo career and his eventual departure from popular culture. It is unknown why he chooses to watch these videos without pants. It could be symbolic of the raw and personal nature of the documentary series, a reflection of Williams’ open and honest personality, or simply a display of his natural inclination towards exhibitionism (which is already well-known).

For some unknown cause, the underwear accentuates the self-indulgent atmosphere. The footage mainly features Williams, with his on-and-off collaborator Guy Chambers as the only other main character (who also filmed most of it). With the exception of a short appearance from his wife, Ayda Field, there are no other individuals providing commentary. This is Williams talking about himself: a suffocating, self-reflective, four-hour-long speech given by Robbie about his past and present, discussing the struggles with depression, anxiety, and addiction that have been intertwined with his immense fame and seemingly defined his entire existence.

Well, perhaps not his entire life. The documentary, which is directed by Joe Pearlman (Lewis Capaldi: How I’m feeling Now), launches into action with Take That – “The most popular British group since the Beatles!” says Cilla Black, during the initial flash of fun retro TV footage – providing no information about Williams’s childhood. Pre-Ayda, his romantic life is also mired in ambiguity: there is a lot of footage of a 2000 holiday with Geri Halliwell but it is never clear whether they are actually an item.

Rather than sugarcoating it, we are given an honest portrayal of Williams’s rollercoaster career. He leaves Take That in anger towards the group’s golden boy Gary Barlow, and then spends a year indulging in drugs at Groucho. His solo comeback, aided by Chambers, starts off rocky but eventually skyrockets to success. For the next ten years, he is a superstar before struggling with severe anxiety. He takes a break from performing, falls back into addiction, meets Ayda, overcomes his struggles, reunites with Take That, starts a family, and ultimately re-emerges as a highly accomplished performer.

It’s impossible not to compare Robbie Williams with the other Netflix documentary about a British icon released a few weeks ago. Born just over a year apart, Williams and David Beckham were both working-class English lads who struggled at school before becoming teenage stars and then, here at least, colossally, traumatically famous, pursued with malicious glee by a dangerously unchecked tabloid media. In their overlapping heydays, these men were the culture. In their crystallisations of late-90s Britishness, they remain powerful vectors of millennial nostalgia.

However, the contrasts between the two are stark. Beckham is reserved to the extreme, while Williams is an animated chatterbox with a sharp sense of humor (could he have been a successful comedian? Let’s discuss). Beckham is driven by a deep love for his sport, while Williams appears to lack joy in his music. The documentaries themselves are vastly different as well. Beckham’s is a carefully crafted representation of his legendary soccer career, filled with entertaining trips down memory lane and interviews with notable figures. In contrast, Williams’ documentary is a dark, self-destructive journey through his past struggles, avoiding any mention of his professional successes (but let’s not forget, Rock DJ will always be loved by this millennial).

The reason for this could be that the celebration is conflicting with the negativity portrayed in this personal story on the screen. Williams is visibly struggling; his on-stage panic attacks are difficult to witness. He is dissatisfied with his own material, desiring indie credibility rather than mainstream success (like “Karma Police” instead of “Karma Chameleon”). His overall unhappiness often manifests as aggression, mood swings, and a tendency to direct sharp remarks towards his colleagues – and sometimes humorously, towards the press (Journalist: “If you weren’t a musician, what would you be?” Williams, with a serious face: “A pig farmer.”).

The movie implies that it was the sudden rise of Take That’s fame that caused Williams to experience trauma. However, in order to regain his success and seek revenge against Barlow, he sought even more fame and attention, as seen by the continuation of this series. He also attributes his second breakdown to the constant pressure of being a solo performer, but struggles to share the spotlight with others, first with Barlow and then with Chambers, whom he parted ways with in 2002.

The content is disheartening, but the mood changes when we get to Williams’s 2006 song Rudebox. It was heavily criticized by the media and you can see that Williams is still affected by the negative feedback. However, he is extremely earnest about this absurd and silly rap song, making the situation unintentionally humorous. It’s difficult to determine whether to find it amusing or distressing.

It is unlikely that you will do either. The negative impact of fame on one’s mental health is clearly not amusing, and Robbie Williams serves as further proof that being a celebrity is a burden and an addictive behavior. As a result, the series comes across as a chance to voyeuristically observe disaster. However, it is difficult to sympathize with Williams. This documentary, focused solely on him, has shown to be detrimental in creating an emotional connection with him.

Source: theguardian.com