“Review of I Seek a Kind Person by Julian Borger: The Classified Ads That Rescued Jewish Children from the Nazis”

W

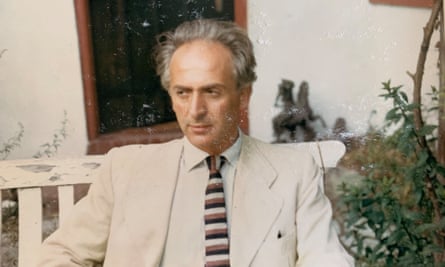

When Julian Borger was a child, he remembers feeling like his family had covered up something uncomfortable and raw with layers of tasteful off-white paint. His father, Robert, was a challenging and discontent psychologist who struggled with feeling like he belonged nowhere as a refugee from two places. When his grandmother Erna came to visit, she would often arrive late and insist on cooking traditional Viennese dishes from scratch, unpacking her plastic bags on the already set kitchen table.

Erna and 11-year-old Robert, who were Jewish refugees from Vienna escaping Nazi persecution, arrived in England in October 1938, as known by the rest of their family. Erna had received a visa to work as a maid, and Robert was taken in by Nancy and Reg Bingley in Wales. However, the family did not share any further information about their journey or the emotional toll of being uprooted and separated.

In 1983, at the age of 22, Borger’s father committed suicide. Many believed it was due to financial struggles and feelings of inadequacy, but Nancy Bingley had a troubling perspective: “Robert was ultimately a victim of the Nazis. They finally took him down.”

Borger has spent a considerable amount of time trying to move past familial ghosts. He relocated from England and has held various positions for the Guardian across the globe. However, a recent encounter served as a reminder that his grandfather Leo had posted a short advertisement in the Manchester Guardian (now known as the Guardian) in 1938 seeking a caring individual to educate his 11-year-old son, Robert, who hailed from a respectable Viennese family.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Borger found approximately 80 hidden advertisements among crossword puzzles and radio schedules. These ads were emotional pleas from desperate parents attempting to rescue their children. Borger was profoundly moved by these brief messages and felt compelled to learn the outcomes of each story. In his impactful new book, he details the fate of seven of these children.

Some individuals were unable to flee continental Europe and were caught in the grip of the Nazi regime’s genocidal actions, while others experienced vastly different circumstances. Gertrude Langer, for example, initially came to England but later discovered that her parents had successfully made it to Shanghai. Upon arrival in the Chinese city, she found that a community of fellow refugees had created a “Little Vienna” with restaurants and cafes. However, this peaceful existence was short-lived as the Japanese formed an alliance with Germany and began to restrict Jews to a cramped ghetto with limited access to food. Fortunately, Gertrude and her new husband Ted were able to secure passage to the United States, although the poor exchange rate required them to hire a rickshaw to transport a large sum of money in local currency.

George Mandler, after arriving in the US, later returned to Europe in 1944 as a member of American military intelligence. He found satisfaction in obtaining information from German prisoners of war, occasionally using the threat of handing them over to the Russians. His group played a role in evacuating prominent scientists and even gained a French chef who took control of the finest wine from grand estates.

The findings of his research also revealed more information about Borger’s family background. He had only known his great aunt Malci as an elderly and melancholic woman living in a small apartment in Vienna. However, her earlier life was filled with intrigue and excitement. She had married a communist activist who was possibly a spy for the Bolsheviks. He was eventually deported from France and disappeared, leaving her to care for his two young stepchildren. During World War II, she sought refuge in a French convent while her stepson Mordechaj played a crucial role in the Austrian Jewish resistance by infiltrating Nazi organizations, including a major steelworks.

Several books have been written about the lives of Viennese Jews before and during World War II, but Borger presents a unique collection of stories that are connected by a small newspaper advertisement and then branch out in various directions like a vibrant array of colors. It was especially exciting for Borger to discover that one of the children, Lisbeth Weiss, was still alive at 91 years old, with vivid memories of the world her father grew up in – a world that Borger had been trying to envision.

Additionally, Weiss imparted knowledge to Borger about his father’s emotional state. Despite her involvement in Holocaust education, she made a conscious effort to strike a balance between confronting and avoiding the traumatic memories. Borger reflects on how dwelling too much on the past can be limiting, while completely ignoring it can lead to it controlling one’s life. Finding a balance between the two can bring a sense of freedom and contentment, something that Borger’s father was unable to achieve.

While working on his book, Borger came to the realization that he harbored feelings of “resentment” towards his father. However, the process also revealed a remedy in the form of a deeper understanding. This adds an intriguing perspective to the existing body of literature on inherited trauma.

Source: theguardian.com