H

How can one assess a collection of music writings by the editor of the New Yorker who has won a Pulitzer Prize? Offering compliments would sound like a job application, while a harsh criticism would be overly argumentative. In a 2016 article about the late Leonard Cohen, David Remnick recounts a conversation between Cohen and Bob Dylan in which they discussed their achievements. According to Dylan, Cohen was “number one” but he himself was “number zero”.

Remnick’s stuff is noisomely good. Rightly or wrongly, the New Yorker is often held to be the loftiest spot left in print, where the business of stringing sentences together on interesting topics still exists in an exalted form, insulated from the closures, compromises and clickbait that prevails elsewhere.

Despite its outdated use of diaeresis (cooperation! Reemerge!), this publication values the arts just as much as it values its analysis of current events. And the editor-in-chief, Remnick, is a unique individual who not only oversees the journal of record for liberal intellectual discussion (at least in North America), but also finds time to personally write extensively on topics such as Russia, Muhammad Ali, and Barack Obama.

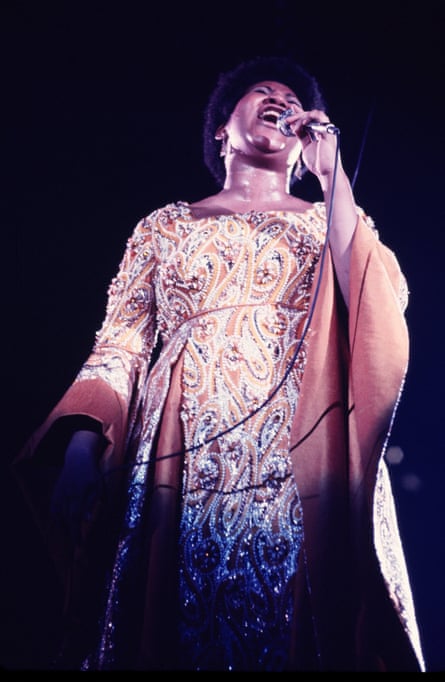

Holding the Note is album-length, pulling together 11 of Remnick’s long-form New Yorker pieces on people such as Bruce Springsteen and Mavis Staples, Luciano Pavarotti and Aretha Franklin. They are artists who occupy a place beyond genre, in what you might call deep canon – celebrated, storied, complex; older or gone.

Excluding Pavarotti, a member of the Beatles (Paul McCartney) and a member of the Rolling Stones (Keith Richards), the majority are American and align with Remnick’s fascination with legendary figures in American culture. The youngest among them is likely Springsteen. This is not a criticism of Remnick – he recently conducted an interview with Gen Z pop sensation Olivia Rodrigo for the New Yorker Radio Hour podcast – but instead acknowledges that these essays focus on concerns prevalent in the late 20th century, as these artists navigated their careers during the end of the baby boomer era. In the foreword, Remnick reveals that he met with these accomplished individuals after their commercial peaks. However, what unites them all is their determination to “hold the note” and continue working – or, in the case of Chicago blues artist Buddy Guy, keep an entire genre alive.

Remnick, who is now in his sixties, was also present earlier in the story. Growing up in a family that was passionate about jazz, he has a personal and deep understanding of the work of Patti Smith and Bob Dylan. As a young person, he had the opportunity to see them perform, as well as other musicians mentioned here.

From an outside perspective, it may seem that writers for The New Yorker spend their time cleverly discussing the perfect placement of a comma. They also appear to have ample time to write extensive profiles of individuals who give them unrestricted access. These articles by Remnick often live up to the stereotype, standing out not only for their depth and liveliness, but also for the extensive time he devotes to interviewing both the subject and those in their circle.

His levels of access are exceptional. Dylan doesn’t actually talk to Remnick for his – still excellent – Dylan piece, in which he puts forward a “unified field theory of Dylan”. But he does get Dylan to talk about Cohen, and it’s no token pullquote, but rather paragraphs of erudite dissection, both technical and effusive.

Remnick spends time with Paul McCartney at both his Hamptons residence and his Manhattan office. He travels to Singapore to write about Pavarotti for a 1993 publication, which turns into a long-term project as the opera singer undergoes knee surgery before returning to tour. Remnick accompanies him on private flights and in dressing rooms.

Despite the abundance of opportunities in this field of journalism, the standout piece is one that focuses on a more distant subject. In the May 2008 issue, Remnick wrote a profile on Phil Schaap, a Columbia University radio host who has since passed away. Schaap was a devoted jazz fan and expert on the intricacies of saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker’s music.

Schaap was raised in the midst of jazz musicians, who considered him a talented child prodigy. However, he also possesses a compassionate heart. During a visit with author Remnick, Schaap introduces him to Lawrence Lucie, a musician who passed away in 2009 and had direct connections to the golden era of Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington. They meet Lucie at his nursing home.

Remnick skillfully portrays the passion and absurdity of niche interests with a sense of respect and humor. In his efforts to revive lost recordings of Parker’s performances, Schaap estimates that he only earned “0.0003 cents an hour”. According to Remnick, jazz only accounted for 3% of music sales in the US in 2008, and even that includes artists like Michael Bublé and Kenny G. The article mourns the decline of jazz as a vibrant and relevant art form, highlighting one man’s dedication to preserving this quintessentially American and 20th century genre.

Source: theguardian.com