“In the past month, I have been unable to express myself effectively due to a lack of language,” shares Adania Shibli as she reflects on feeling silenced.

W

As a young girl, Adania Shibli’s initial experience with storytelling took place on her family’s almond and olive farm in Palestine. It was her mother who first told her stories, gathering the children around when there was no electricity and they were afraid or unable to read. Her mother’s stories continued until the light returned.

Shibli’s mother was illiterate, so the stories she shared are now only remembered by Shibli’s siblings. During a video call from Zurich, where she is staying as a writer-in-residence, Shibli recalls one of these tales from her childhood. As she talks about her family, a wide smile lights up her face. Although the details of the story fade, one lesson stands out: a man’s carelessness with words leads to his downfall.

Shibli has a specific intention in sharing this anecdote. In October, she was supposed to receive the LiBeraturpreis, an accolade presented by the German literary organization LitProm to authors from regions in the global south, at the Frankfurt book fair. However, she was unceremoniously uninvited via a brief email, with LitProm citing the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine as the reason. A letter expressing disapproval of the postponement of her award was signed by over 1,500 authors, including Nobel laureates Annie Ernaux, Abdulrazak Gurnah, and Olga Tokarczuk. Despite this, Shibli has yet to publicly address the situation.

Despite the numerous requests on her desk, she traveled to Korea for a literary festival and to have her book translated. Prior to this, she had promised people in Seoul that she would attend and she was determined to keep her word. “When you make a commitment, it’s important to follow through.”

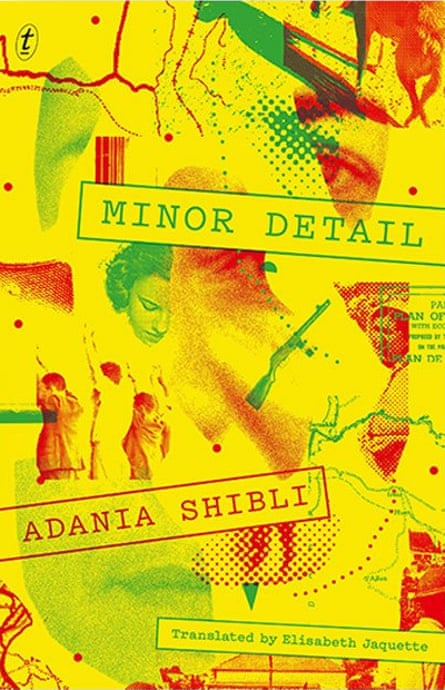

In her 25 years of writing, Shibli has only published three short novels due to her perspective on language. These novels, titled Touch, We Are all Equally Far from Love, and Minor Detail, are delicately crafted and portray the inner thoughts of characters who have been oppressed by language. Shibli’s writing showcases the resilience and beauty of her characters despite being confined by language, which she refers to as a “scarred” tool.

Minor Detail is a book that tells two interconnected stories. The first takes place in August 1949 and follows an officer who is leading a group in removing Arabs and Bedouins from the southern Negev. During this time, he abducts and ultimately rapes and murders a Bedouin girl. In the second half of the book, a woman who was born exactly 25 years after this crime reads about it in the news. She then embarks on a journey to uncover more information, facing the challenges that come with being a Palestinian trying to access archives and libraries to learn about her past.

Adam Thirlwell, a novelist, describes Adania’s work as a miraculous fusion of political themes and existentialism. He praises her ability to skillfully intertwine intention, physicality, and setting with her distinctive control over composition and darkly humorous viewpoint. Thirlwell also notes the novel’s complex exploration of empathy and cross-cultural inquiries.

Shibli spent 12 years writing the book, while also relocating to London to obtain a PhD in media and cultural studies. Her thesis focused on visual terror during the 9/11 attacks. This was a tumultuous time due to the second intifada, and Shibli struggled with nightmares. Being away from her native language allowed her to gain a closer understanding of it, which is reflected in the opening line of the book’s second section: “After completing the task of hanging curtains over the windows, I rested on the bed.”

In the spring of 2022, Minor Detail received overwhelmingly positive reviews upon its release in Germany. However, prior to the Frankfurt book fair, journalist Carsten Otte published a review criticizing the book for portraying all Israelis as anonymous perpetrators of sexual assault and murder, while casting Palestinians as victims of either poisoned or trigger-happy occupiers. Author Shibli believes that this review influenced the postponement of an award she was set to receive. Nevertheless, she states, “I viewed this situation as a diversion from the true source of suffering, nothing more.”

Shibli mentions that all the Palestinian figures in the story do not have specific names. In fact, the soldier in the novel only sees their shadows for the first time: “Their thin dark shadows would occasionally appear in front of him, flickering between the hills. But whenever the vehicles approached, they would find no one there.”

Shibli’s family background is of Bedouin descent. Her predecessors arrived in Palestine a millennium ago as soldiers serving under Saladin, the initial sultan of Egypt and Syria. Initially, her family had control over a vast expanse of land, but it eventually diminished due to British authority over Mandatory Palestine and the establishment of Israel. These events hindered their nomadic lifestyle which, as Shibli explains, interfered with their hold on both land and people. Ultimately, the Israeli government claimed all of the land, offering Shibli’s father the opportunity to reclaim some if he took it from another Palestinian family. He declined.

Shibli grew up on the farm that remained, starting work at the age of four. She learned to read and write Arabic from one sister and English from another, and would sneak books out onto the fields. She jokes, “I spent more time with goats than my parents.” When she was nine, a sister gave her a notebook to write in and she fell in love with writing. In university, she wrote texts and submitted them to top magazines in Palestine. In her early twenties, a piece she wrote caught the attention of renowned poet Mahmoud Darwish. He invited her to his office and asked her to write a four-page text. She did, and he encouraged her to write more. This led to the creation of her novel, Touch.

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

After approximately three decades, Shibli summarizes the impact of linguistic dominance and erasure discussed in her book as follows: “In Palestine-Israel, I, like countless others, learned that language is not simply a means of communication. It often conceals instead of revealing, containing within its silence infinite possibilities that have nothing to do with expression. Language can be targeted, mistreated. Yet, it still has the power to provide the utmost freedom of existence and love that may be unattainable in actuality.”

For Palestinian individuals, their language is a source of pain due to the absence of certain words. How does one express what they cannot hear? As Shibli points out, this process often involves omitting words like “Palestine,” which are not represented on road signs or maps. Additionally, Arabic and Arab-related terms are seen as taboo and even used to describe undesirable jobs.

Shibli often personifies language, speaking of it as if it were a living entity with its own intentions. In the wake of increased violence in Israel and Palestine, she has found herself unable to express herself through words and is concerned about the absence of language. She has long feared losing her ability to communicate and in recent weeks, her words have eluded her. She reflects, “I have always worried that one day I would wake up and language would be gone. And in the past four weeks, it has deserted me, leaving me unable to convey my thoughts.”

I have come to realize that losing our ability to communicate is a result of enduring pain. The unfathomable suffering of those in Palestine-Israel who are facing a new level of cruelty, as well as the individual pain of losing the hope for a better future where we could come together and learn from our pain instead of causing harm to others.

She acknowledges that the recent influx of media inquiries and backlash for her lack of response has made her reflect on how we often view silence as something negative rather than embracing it as a natural response to suffering. She believes that literature is the only outlet that allows for and welcomes silence.

Before being uninvited from the book fair, she had started drafting a text for her acceptance speech. The topic was book banning.

Source: theguardian.com