All English language becomes fresh in the Caribbean mouth. There is nothing the enslaver has given us that we have not reimagined new, made weapon. There is no misfortune we cannot, as we say, tun our hand, mek fashion. This quicksilver sense of ingenuity and battle-worn verve born of necessity to Caribbean people is at the heart of this compelling new novel by Moses McKenzie. Fast by the Horns is a fascinating depiction of Black immigrant life and Rasta boyhood in 1980s England. With the sharp and delectable music of its dialect, the book grabs you by its teeth from the first page and never quite lets go. At its best, this is an urgent novel of ideas, constantly propelled by the narrator’s wildfire voice, written almost exclusively in beautiful Rastafari vernacular.

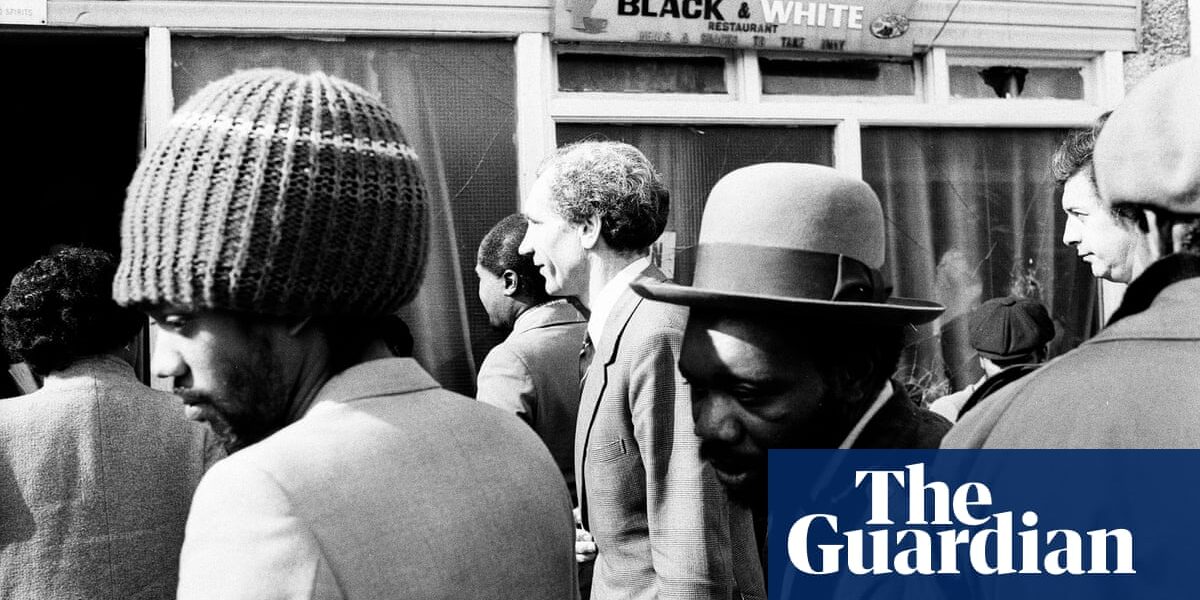

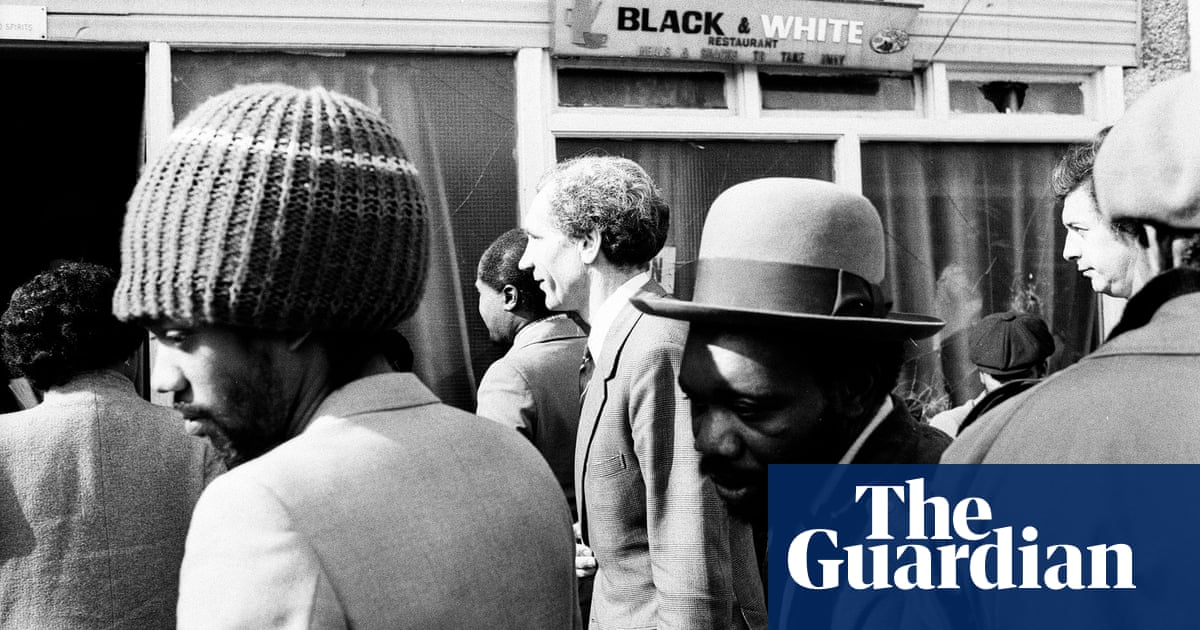

At the novel’s heart is a historical portrait of Britain’s Jamaican immigrant community, and its inescapable ties to its colonial legacy. Centring on St Pauls in Bristol, two Englands swiftly emerge: one for the Black immigrants who are constantly harassed by the police and face high unemployment rates and crumbling infrastructure, and one for those Britons who claim the countryside, the yards, the banks, the pigs, and eventually even the neighbourhood’s Black children.

McKenzie deftly weaves the UK’s history through a series of explosive events spanning a few days. The novel focuses on a hardscrabble group of Rastafari and their unbending ideals of Black liberation and repatriation to Africa. It begins and ends with clashes between the police – Babylon – and the citizens of St Paul’s, protesting against the brutal degradation of their people. As was true of the Rastafari movement in Jamaica, the Rastafari in the novel are relentlessly harassed, beaten and arrested.

The primary victim of the violence is the narrator Jabari’s father, the incendiary Ras Levi, a character drawn with striking familiarity. He rules with an iron rod and walks an iron path of righteousness that eschews any sense of nuance. Ras Levi is a man who leads with his temper, throws himself headfirst into any battle and puts his ideals and egomaniacal pursuits before the safety of his family. His teenage son, Jabari, describes him as a man who has “a way of turning conversation inna a sermon that make talking to him difficult”.

The Rastafari are seen as the main “troublemakers” by both the cops and the other inhabitants of St Pauls. “It all start with these Rastafarians,” one character decries, “them get all in the yutesdem mind and mash up them head, create trouble where trouble isn’t.” But throughout the novel, Babylon’s unprovoked violence against the Rastafari and the inhabitants of St Pauls is rampant. Heads are smashed to the ground, ribs are broken with batons, eyes are bloodied, houses are ransacked and set aflame, bodies are assaulted and violated. In the end, the ultimate violation is the forcible shearing of Ras Levi himself, which sets a match to the powder keg of tension between St Pauls and the cops.

“England was telling us who she was and what she was proud of,” Jabari muses on the institutional racism in the country, deep and riverine. Here is British history laid bare, with a crucial statement on English society. Here is a love letter to the Windrush generation who came to fight and build and labour for a nation who then left them the bleak, shelled remnants of the city after the second world war, and the scorn of their fellow citizens.

Fast by the Horns is a rallying cry for these immigrants. But at its most tender, it’s also about their unsutured wounds. The fissured memories of Jamaica present a desire to define not just what home means, but where home is: Jabari’s mother Nefertari longs for Jamaica, “but she never spoke of home when Ras Levi was in the house. Ras Levi look to the future not the past, and Jamaica was the past, so she save it for herself.” Ras Levi believes his calling is to convert Black people in England to Rastafari and to repatriate to Ethiopia, the promised land. To him, home is a place he has never seen, and to her, home is the heavy song on her silent tongue. Jabari, who has only known England, parrots his father’s ache for Zion, but is eventually plagued by a doubt seeded by this doubled unbelonging.

As the main characters, Jabari and Ras Levi embody the male-centred thinking that dominates a lot of Rastafari rhetoric. And while the novel tackles some of the underlying patriarchal systems of Rastafari, it never quite interrogates it fully. Nefertari lies only on the outskirts of the narrative, eerie in her silence, and an accomplice to Jabari’s physical abuse at the hands of Ras Levi. She is described as having been pushed into her silence by an external force that becomes clearer later. There is a sadness to Nefertari, her voicelessness, her waiting in the margins, and she never quite emerges into the novel.

A welcome counterpoint to the silent Rastawoman are the headstrong and firebrand women of the women’s centre, Mother Earth, who are denigrated by Ras Levi as “feminists” and “hungry to be a man”. Among them are Makeda and Joyce, magnetic female characters that stand like compass points amid the novel, and who eventually affect the inner moral questioning of Jabari.

As often happens when indoctrination is coupled with familial violence, doubt follows. At the root of Jabari’s doubt is the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, in which God tells Abraham to kill his son Isaac as a show of faith. Ras Levi sees this parable as a guide – the ultimate sacrifice of Jah’s ultimate soldier – but Jabari wonders whether it’s the ultimate betrayal. Would Ras Levi sacrifice him, too, if it came to it? This question is answered at the novel’s climax, in one last calamitous clash with, and uprising against the police.

after newsletter promotion

This clash also centres on the other major plot point, which involves a young Black girl named Irie who has been taken from her Black mother by social workers and adopted by an affluent white couple. Young, idealistic Jabari believes this is unforgivable and wants to keep the girl among her own people, while Makeda and Joyce have more complex opinions on the matter. As these points of conflict converge, the novel races to the end a bit too swiftly, and I found myself longing for more moments of pause in its unravelling. McKenzie dispels the gathering power of Jabari’s doubt too easily. In the complexity and toxicity of his relationship with his father and on the matter of blind sacrifice, there seemed more to uncover in the ways unquestioning faith binds us to a generational violence.

The book seems to suggest that the message and mission of Rastafari itself is also up for sacrifice, “caught fast in a thicket by its horns”. This is an idea I find unendingly fascinating, but one that breezes by too quickly to really give root to its implications. Jabari’s eagerness to lionise Ras Levi at the end – with as much wisdom as a 14-year-old can muster – seems too quick a turn after the harrowing reveal of a core childhood trauma at the hands of his unrepentant father, but one that also rings very true for a child moulded by violence. I only wished to stay with the captivating spirit of Jabari, in his familiar loneliness and the dark torch of his boyish questioning, for just a bit longer.

Source: theguardian.com