Could the judges potentially talk themselves out of making the right choice for the Booker Prize in 2023?

Y

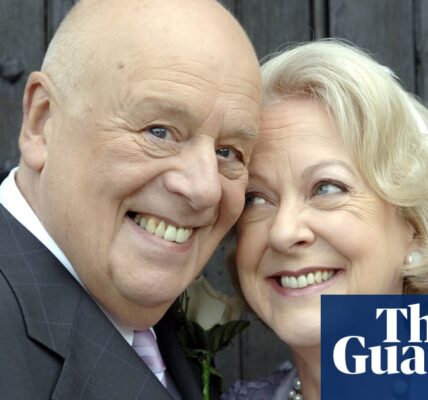

It’s that time again: the winner of this year’s Booker Prize will be announced next Sunday. While everyone has their personal favorites and it’s easy to criticize the judges for missing certain novels, we do not know the criteria they use to make their decisions. The list of 150 titles is not public and it’s likely that many factors influence its composition. In the past, I have heard of a well-known British author who declined to be considered for the prize. Furthermore, awards have become brands in themselves and strive to establish their own identities. For example, was Barbara Kingsolver’s novel Demon Copperhead excluded from the list after winning the Pulitzer and Women’s prizes for fiction?

A panelist, James Shapiro, who specializes in Shakespeare, recently expressed discomfort with historical fiction. This may have played a role in the exclusion of two highly praised novels, The Fraud by Zadie Smith and The New Life by Tom Crewe, from the longlist. However, one historical novel, This Other Eden by Pulitzer Prize-winning American writer Paul Harding, did make the shortlist. This should come as no surprise, as the chair of judges, Esi Edugyan, herself praises its quality on the book’s cover, released in February of last year.

Based on a real event, this novel tells the story of a racially diverse community in New England who were forcefully removed before World War I. While Edugyan may support it, I personally find it difficult to fully appreciate. The plot follows the descendants of a former slave as a missionary, who has hidden prejudiced thoughts, tries to protect one of them – a talented painter who appears white – by having him relocated to a friend’s property on land.

The central focus is on the ill-fated love story between the protagonist and his landlord’s Irish housekeeper. However, the author heavily relies on lengthy passages of storytelling to create dramatic irony, as the events unfold through various perspectives – the artist’s, the maid’s, and his family’s – when she arrives on the island to uncover the painter’s past.

In his previous book, Enon, Harding was able to incorporate some comedic elements into the story of a father grieving over the loss of his teenage daughter in a car accident. However, in This Other Eden, Harding takes a more serious approach, showing his commitment to handling difficult subject matter with care. While he does evoke feelings of sadness and shock through the tragic events, the book does not glorify or justify the violence that occurs.

I am concerned about Paul Lynch’s novel, Prophet Song (Oneworld), which takes place in modern-day Ireland during a war between a totalitarian government and rebel fighters. The story follows a mother of four in Dublin after her husband, a trade unionist, is unjustly detained. The focus is on her struggles to maintain a sense of normalcy while the country falls into chaos, from abductions to air raids. This focus creates a powerful contrast within the novel – as the bombings escalate, the protagonist’s father calls to complain about his neighbor’s ivy – but it also places the novel firmly within the realm of a thought experiment. It is strikingly apolitical, lacking any clear historical context, and ultimately feels almost disgustingly indulgent in its attempt to elicit sympathy for refugees by portraying them as privileged Europeans. When Eilish remarks that it feels like a “filmed transparency of a foreign war has been placed upon an image of the city,” she perfectly captures Lynch’s intentions.

However, the intense action scenes maintain their powerful impact even upon multiple readings, and the unsettling feeling it creates may actually work in its favor – regardless of what else it may be, Prophet Song is a book that will spark debate.

I preferred books that were quieter on the list. I commend the judges for highlighting “If I Survive You” (Fourth Estate), which is a captivating debut written by US author Jonathan Escoffery (a previous student of Percival Everett, who was shortlisted last year for “The Trees”). The story initially delves into the exploration of second-generation American identity through the perspective of Trelawny, a literature graduate with Jamaican roots. He struggles with his self-esteem, feeling like he’s always second-best in his father’s eyes compared to his brother Delano, who is a successful tree surgeon. After graduating during a recession, Trelawny takes on odd jobs for money, including one where he is hired by a woman who posted a classified ad seeking someone to physically harm her.

The relationship between father and son is filled with tenderness, making this a deserving winner. It combines humor and sadness while challenging assumptions about race. The opening sequence may seem like a simple exercise in voice, but the second-person narration delves into the complexities of internalized racism. As the story progresses, Escoffery’s talent for creating tension shines through, particularly in Delano’s disastrous attempt to retrieve an impounded cherrypicker for work. In the title story, Trelawny becomes entangled in a wealthy white couple’s disturbing sexual game. This collection of linked stories is openly advertised as such on the dust jacket, a first for this prize, which is now awarded to “longform fiction.”

One of the standout debuts of the year is Western Lane (Picador) by Chetna Maroo, the only British author among the nominees (it’s worth noting that she got her start in writing from magazines in the US and Ireland). The judges seemed to have a strong interest in stories about families, but this book’s simplicity sets it apart. It is told from the perspective of 11-year-old Gopi, the youngest of three daughters in an Indian family living in south London. After their mother’s death, Gopi’s father teaches her how to play squash at a local leisure centre. As she prepares for a tournament, the story unfolds and reveals the unspoken dynamics between Gopi and her father, as well as with an older boy she meets at the leisure centre, her sisters, and her childless aunt and uncle in Edinburgh where she is expected to move.

This is a captivating story of both family and sports. The touching novel tackles the theme of grief in a sincere and powerful way, using simple language to convey deep emotions. The narrator’s limited understanding of her circumstances is portrayed without turning her into a source of mockery. It is truly impressive how Western Lane manages to evoke such strong feelings with just a few words.

The Bee Sting, written by Paul Murray and published by Hamish Hamilton, is a hefty book that could easily fit the other shortlisted books within its pages. It explores similar themes as the others, such as familial misunderstandings and the collapse of civilization, including the looming threat of it. The story follows a struggling car salesman who is married to the daughter of a bare-knuckle boxer, and his attempts at prepping for potential disasters ultimately lead to disastrous consequences. Clocking in at 650 pages, the novel reads like a soap opera with a tightly-woven plot that keeps readers on the edge of their seats. If it wins the Booker prize, many readers will be delighted to receive it as a Christmas gift.

Is this novel the clear winner, or will the judges overthink it? A critical 3,000-word article in the London Review of Books demonstrates the potential consequences of dwelling on it too much. Also, keep in mind that the Booker Prize doesn’t necessarily recognize the best novel of the year; rather, it is the book that endures a rigorous nine-month process of being read and debated multiple times.

As a result of this, I am curious as to whether Prophet Song or Sarah Bernstein’s Study for Obedience (Granta) will be chosen. Bernstein, a Canadian currently living in Scotland, was recently named one of Granta’s best young British novelists and has twice won Canada’s prestigious Scotiabank Giller prize (previously won by Edugyan). Study for Obedience has stayed with me since I read it in March. While I did not enjoy it then and still do not love it, it stands out amongst novels about family – an enigmatic and thought-provoking work steeped in the violence of the 20th century. I am unable to fully articulate what the novel is about, which is why I believe it deserves examination.

The main character is a woman without a name who relocates to an unspecified nation to manage her strange older brother’s household duties. Part of her responsibilities include washing his back, and she is only allowed to watch television by reading lips (he believes subtitles affect the lighting in the room). Unusual interactions with the community never escalate into conflicts. Instead of intense moments, we feel uneasy and anxious: hidden beneath the surface lies the history of genocide and displacement of the main character’s family.

The convoluted storytelling deliberately creates a sense of entrapment within our own thoughts, with its frequent use of compound sentences and negative phrasing.

Is it possible to compare this to the precise and direct writing style of Maroo’s sentences that hit the core? I don’t envy the judges. While they have mostly chosen books that celebrate the joy of storytelling, Bernstein’s book challenges narrative – and perhaps it will be declared the best on 26 November by judges who can’t be expected to agree for a whole year on the greatness of The Bee Sting.

Source: theguardian.com